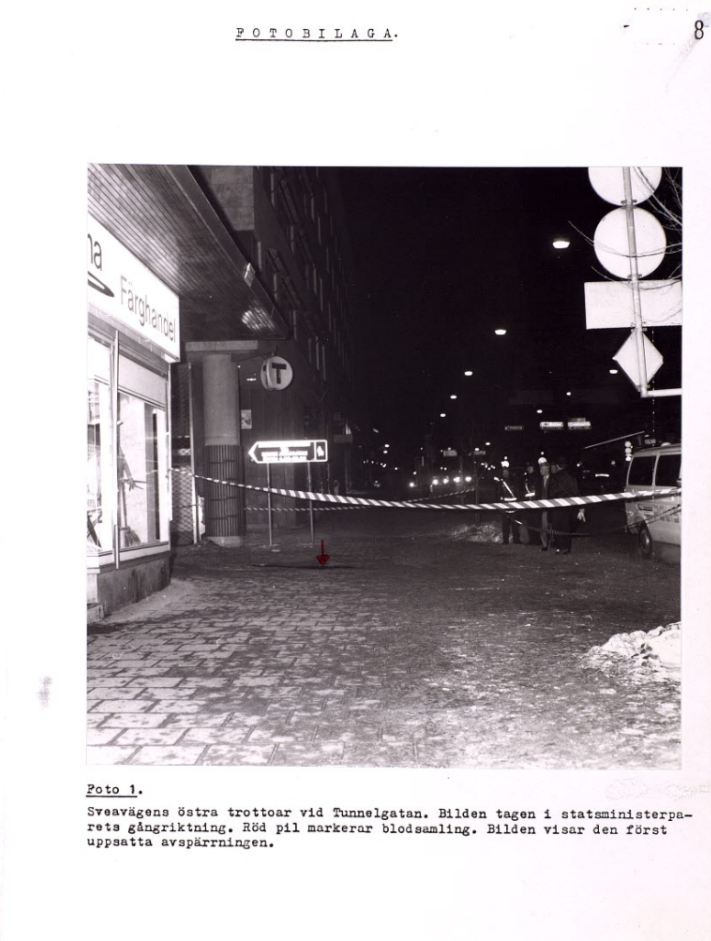

Police photograph from the crime scene. Photo: Courtesy Swedish Police

When a Swedish prosecutor announced at a June press conference that the three-decade probe into the killing of a Swedish prime minister would be closed since there was “reasonable evidence” that the assailant had been identified, journalist Thomas Pettersson’s phone began ringing hot.

Two years earlier, Pettersson had published a magazine article and book about his own investigation into the 1986 killing of Social Democrat Olof Palme, which led him to pin down as the assailant a graphic designer called Stig Engström who worked just a short walk from the crime scene. And when the prosecutor concluded his two-hour-long press conference earlier this summer, it was described by the Swedish media as akin to a summary of Pettersson’s book.

The prosecutor and the journalist had, in fact, reached the same conclusions and on nearly identical grounds — and that is why Pettersson was fielding phone calls from Swedish and international press who wanted his take on the matter.

When GIJN reached Pettersson by phone in his home in Gothenburg in southwestern Sweden, he was hard at work on an updated edition of his book “The Unlikely Murderer,” which is due out this month and for which Pettersson has now sold the film rights.

“This is an incredible story about a man who falls through the cracks of the system and succeeds in getting away with a crime despite making himself known to the authorities,” said Pettersson.

So how did a freelance journalist manage to beat the cops on their own investigation? After all, the Palme probe was so wide in scope that is has been compared to the investigations into the 1963 assassination of United States President John F Kennedy and the 1988 Lockerbie aircraft bombing.

Pettersson’s book on the killing of Olof Palme. Photo: Offside Press

The Shooting of a Premier

Let’s first briefly backtrack to the fatal night of February 28, 1986, when, at 11:21 p.m., then-Prime Minister Olof Palme was shot dead while walking home from a cinema in central Stockholm with his wife, Lisbeth. The couple had just said goodbye to their son and his girlfriend, and since Palme had dismissed his security team earlier in the day, they were unguarded when someone shot him from behind at close range. A second bullet grazed Lisbeth Palme’s back and the assailant fled the scene via a narrow flight of stairs.

In the decades since the murder, there have been numerous theories as to who was responsible. For instance, there was the pursuit of Christer Pettersson, an alcoholic and drug user who was convicted of the murder in 1989 but then freed by an appeals court due to lack of evidence around his motive.

There was “the South African connection,” a theory that held that the killing was carried out to avenge Palme’s criticism of the apartheid regime. The theory about the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) led to the questioning of 12 members of the group in 1997 but resulted in no arrests. Another line of inquiry led investigators to Engström, who became known as “the Skandia man” for the name of the insurance company where he worked as a graphic designer. Engström was an early witness who had died in 2000.

However, the police did not pursue the Engström lead in earnest until Thomas Pettersson helped provide key information about him and then published his own case for why Engström was the one who fired the fatal shot on that cold night in 1986.

Pettersson had started his own investigation into the murder in 2006, but it took a year before he zoomed in on Engström. “No one else was pursuing that track at the time,” said Pettersson. “Engström didn’t feature in the police probe or in other journalists’ work, so I wasn’t stressed about someone beating me to a potential story.”

In fact, Pettersson would spend 12 years pursuing the lead, alongside other, paid freelance assignments. “All in all, I’d say I spent about a month a year on this and my work has essentially gone through five phases. Phase one was about getting an overview of the case by reading official inquests, books, and journalistic reports. In phase two, I decided to concentrate on the crime scene itself, and that’s when I also started focusing on Engström, who stood out to me because his own statements to the press and police contradicted those of other witnesses and did not match the known course of events on the murder night.

“By the time I got to phase three, I was working on the presumption that the murder was not a lone wolf act, and I started looking at the potential involvement of various shady organizations. But then, in phase four, I really wanted to get to know Stig Engström and to put myself in his shoes. He was deceased, but by talking to his colleagues, friends, and neighbors I started to get an idea of who he was and what his potential motive had been. In this phase I discovered a neighbor who owned weapons, and that turned out to be a key finding that helped convince me that Engström had the know-how and capacity to carry out the killing on his own.

“As for phase five, well one could say that it’s still ongoing as I’m now trying to delve deeper into Engström’s persona and to understand why he, after the murder, constructed what I maintain is a false narrative in order to mislead the police.”

Over the 12 years of working on the story, Pettersson said, other journalists and a cadre of “hobby investigators” were generous in sharing knowledge and insights with him. He also had access to two extensive state commissions that served as the basic framework for his research.

“The wealth of material available was an asset of course, but at times it was also a problem,” said Pettersson. “Partly because there was so much to sift through, and partly because I had to ‘debrief myself’ in order not to be biased by the material.”

Getting different sources to open up to him, including Engström’s ex-wife, old neighbors, and colleagues, was key in advancing the story. So how did Pettersson get them to talk?

“Establishing trust has been essential because they all knew I regarded Engström as a potential assailant. What worked in my advantage was partly that his ex-wife was very open and that neither she nor the other handful of key sources had grown tired of talking to journalists or police because they simply had not been approached.”

“A disadvantage was that I live in Gothenburg and could not meet these people in person very often as they are in Stockholm [nearly 300 miles away]. It’s much harder to establish trust over the phone but I did manage to nurture these relationships. One thing to keep in mind is to save the most difficult questions until last so as not to risk upsetting one’s sources and losing their trust.”

Trawling Through Documents

Pettersson mentions two other key turning points during his time investigating the story. One was when a wealth of documents was made available online. “When I first started I had to travel from Gothenburg to the Stockholm police headquarters and read documents with a smoking police officer hanging over my shoulder. These days, it takes seconds to get that information online.”

The second turning point came in 2012, when Pettersson contacted Mattias Göransson, editor-in-chief of Filter, the magazine and publishing house that eventually published Pettersson’s story in 2018.

“When Thomas approached me, countless journalists and amateur investigators had already produced a tsunami of reporting on the Palme killing,” said Göransson. “But Thomas’ facts-based approach stood out.”

Göransson continued: “What Thomas presented to me back in 2012 was in fact similar to what prosecutor Krister Petersson would eventually present eight years later at his press conference: namely the basic observations one could make by returning to the crime scene and focusing on who was there that night, instead of being caught up in complicated theories about plots and conspiracies that never actually landed in anything concrete at the site of the murder.

“I was also willing to buy Thomas’ premise that the explanation for why the police had failed to conclude the probe was not because the case was so uniquely complex but rather because the probe had been marred by incompetence from the outset,” Göransson explained. “I had been involved in other major stories that took place during the Eighties and that were marked by similar incompetence on behalf of the authorities. This was not something that surprised me.”

Still, it would take six years before Filter published Pettersson’s story. “We had a list of things that we agreed we had to find out and confirm before we could publish,” said Göransson. “For instance, proof that Engström was able to handle a gun and that he had access to weapons. The items on that list simply weren’t all ticked off until the spring of 2018. Up until that point I offered Thomas support and some resources, but it wasn’t until we had decided to publish that we could guarantee him a fee.”

Pettersson and Filter faced a wave of criticism after the story was published, something that Göransson had counted on, and so there was a plan for how to deal with the media onslaught.

“For instance, we published all source material online so we were completely transparent,” said Göransson. “Of course investigative journalism is not a popularity contest and if your work doesn’t upset someone, somewhere, well then you probably haven’t done your job right! Still, in such situations it can be difficult to be a freelancer, and as Thomas’ editor, I was able to face the media alongside him.”

A major payoff for the long and hard work came in 2019, when Pettersson received Sweden’s most prestigious journalism award, the Guldspaden, or “golden shovel,” from Gravande Journalister (Grav), Sweden’s Association of Investigative Journalists.

As for the formal police investigation, that was officially closed on June 10. The chief prosecutor, Krister Petersson, who took over the investigation in 2017, said then: “In my opinion, Stig Engström is unquestionably the suspected perpetrator.”

“Since the person is dead, I can’t bring any charges against him but have decided to terminate the preliminary investigation,” he said. “My assessment is that after just over 34 years it is hard to believe that any further investigations would add anything. I believe we have come as far as can be expected.”

Pettersson receiving the Guldspaden award. Photo: Courtesy the Swedish Association of Investigative Journalists

Fouad Youcefi, chairman of Grav, said he believes “every single investigative journalist who read the Filter story and then listened to the Palme investigators’ press conference received a confidence boost. It’s crucial to believe in one’s story and to have an editor who believes in it, too, and who backs you up.”

Youcefi added that there are significant challenges in pursuing major investigative work as a freelancer in Sweden. “Anyone who has tried knows how much time and energy is needed even to produce a viable pitch, and so we need brave editors who are willing to develop pitches together with freelancers.”

Still, Pettersson himself believes he also benefited from being a freelancer. “Had I been employed, it would have been difficult to carve out the time to work on this story for so long. Being a freelancer meant I could be flexible, and I knew from the outset that I was in it for the long haul.”

Additional Reading

Nathalie Rothschild is a freelance print and broadcast journalist based in Stockholm. Her stories have aired on the BBC and Sweden’s national radio and her articles have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Haaretz, and Vogue. You can read her work here.

Nathalie Rothschild is a freelance print and broadcast journalist based in Stockholm. Her stories have aired on the BBC and Sweden’s national radio and her articles have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Haaretz, and Vogue. You can read her work here.