Graphic: Courtesy Coda Story

Alexandre Capron expected to find a sinister, well-funded organization when he began investigating a COVID-19 disinformation campaign that had captured the attention of hundreds of thousands of people in Africa and Western Europe.

Newsfeed posts from five popular Facebook pages contained fake quotes attributed to presidents and medical authorities — information with potentially lethal consequences — and appeared to be expertly pitched to exploit resentments among many in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the large Congolese diaspora in France.

Capron, a reporter for France 24’s The Observers, used a set of network-tracking tools — including Hoaxy, whopostedwhat.com, and Facebook’s increasingly powerful Transparency box — to zero in on the organization behind it.

Instead, he found a 20-year-old college student and a 16-year-old school kid in DRC’s capital Kinshasa, “playing a game.”

The 20-year-old page administrator told Capron: “We make up stories to get followers. We give our social media users new information that they haven’t read elsewhere.”

A 20-year-old Congolese student told a reporter that he had gained 60,000 followers in a month by posting fake COVID-19 posts like these. Image: France 24’s The Observers.

Just one of the student’s Facebook sites had 150,000 followers, and its fabricated COVID-19 articles generated 206,000 shares on social media in five weeks.

The forces behind the global flood of deliberate falsehoods about the pandemic are emerging as a toxic mix of fringe ideological groups, commercial scammers, state actors, “dark PR” agents, conspiracy news networks, and even students just seeking attention or tiny financial rewards.

Research by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford suggested that nearly two fifths of all COVID-19 misinformation was completely fabricated. And a study by the Oxford Internet Institute found that COVID-19 disinformation stories produced by Russian and Chinese state media generated far more social media engagement than factual stories by domestic media outlets in Western Europe. The situation is so serious that the World Health Organization says the pandemic has been accompanied by an “infodemic” of misinformation.

Unlike political lies, falsehoods about communicable diseases which are strategically placed and spread have deadly consequences. These include deaths stemming from irresponsible behavior, fake or even poisonous “cures,” and incitement to violence, as has been seen in attacks on Muslim minorities in India.

GIJN interviewed seven reporters and editors working on COVID-19 misinformation, and we found that their views on the role of investigative reporting were unanimous: Investigative journalists should focus primarily on the people and the money behind these campaigns, rather than on debunking the false claims that they generate and spread.

While the journalists we spoke with used dozens of tools to expose the actors behind the fabrications, GIJN has identified six tools and six techniques common to many of the investigations described in the interviews.

“I think we have a responsibility to expose the people and groups who are generating and spreading disinformation,” said Craig Silverman, media editor for BuzzFeed News. “Troll groups, state actors, financially driven groups — all of them need to be investigated. One, because it’s a good story, and, two, because it helps to deter people. It makes disinformation less appealing if journalists are going to be on their trail.”

Silverman recently updated a list of essential open-source plugins and tools to help keep reporters breathing down the neck of those peddling misinformation.

Reporters say that an outstanding collective response by fact checking organizations around the world in 2020 has helped them to go after those shadowy actors.

The CoronaVirusFacts Alliance alone — 100 organizations led by the International Fact Checking Network at the US-based Poynter Institute — has already debunked more than 7,000 COVID-19-related hoaxes in 2020. Meanwhile, the Forum on Information & Democracy has launched a working group to find a policy-based response to the infodemic. And research organizations like the nonprofit coalition First Draft is training reporters on techniques to verify online posts, and to report on disinformation responsibly.

It took First Draft an easy reverse image search to show that this image — widely claimed on social media sites to show COVID-19 deaths in China — was from a 2014 art project in Germany. Image: Courtesy First Draft

Aimee Rinehart, US deputy director of First Draft, said the group was also focused on helping newsrooms shut down dangerous coronavirus-related rumors before they had a chance to go viral.

“We’re seeing the same kind of tropes and ‘othering’ and general levels of hatred for groups that we always see with online rumors, but the icing on this disinformation cake is coronavirus,” said Rinehart. “Instead of George Soros as the frequent target, the bogeyman for trolls now is Bill Gates. There was misinformation before, but disinformation — the deliberate stuff — really started to happen around the ReOpen protests [following the COVID-19 lockdowns]. In the US, we’ve seen horseshoe narratives — the anti-vaccination community on one end of the political spectrum and the Second Amendment [gun rights] people on the other, but united in any content campaign around ‘you can’t tell us what to do.’”

Scoops on Coordinated Disinformation

Investigative journalists broke several bombshell stories about the coordinated forces behind the disinformation that compromised the US elections in 2016 and influenced the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom. One by Silverman revealed that young entrepreneurs in a small town in Macedonia had created at least 140 propaganda websites which had a significant impact on American voters, while a New York Times series expanded on a scoop by Russian reporters of a “troll farm” in St. Petersburg called the Internet Research Agency.

No story on quite that scale has yet been broken on COVID-19 disinformation. But experts say potential scoops on coordinated disinformation are likely out there.

Natalia Antelava, editor in chief of the Tblisi, Georgia-based nonprofit Coda Story, said disinformation had forced many newsrooms into a reactive “whack-a-mole” mode, and that focusing on the organizations and motivations behind the deceptions could be a better path forward.

“I do think debunking has been a diversion for reporters, in many ways,” said Antelava. “We need to be doing proactive storytelling, and not just reacting to someone else’s agenda. I think covering disinformation should be like covering any other crisis. The basics should be the same.”

Graphic: Courtesy of Coda Story

In February, Coda Story investigated a Facebook group, Stop5G International, which peddles false information to attack 5G data technology — a topic that has since become a major disinformation theme in the pandemic. More than 70 mobile phone towers in the UK alone were vandalized or burned by people who believed the narrative the technology was fanning the spread of COVID-19 by damaging human immune systems.

The Coda Story team tracked the manager of the Facebook page to a private basement near Zurich, where one reporter was scanned with a handheld radiation detector when he went to interview the person behind it. However, rather than being scornful in tone, or focusing on some of the outlandish claims, the story respectfully explored the man’s motives and fears, while stating the scientific facts lower down.

Investigations Impacting Disinformation

In May, Armenian reporter Tatev Hovhannisyan found that a local health news website, Medmedia.am, had posted several false and reckless stories on the pandemic, including one that called on Armenians to “refuse all potential vaccination programs.” Hovhannisyan said that story attracted 131,000 views, in a country with only about 3 million citizens.

She also referred to the website’s second-most read story which claimed, falsely, that a morgue was offering cash incentives for family members to sign a form stating that their deceased relative had died from COVID-19.

The site — which she discovered was run by a doctor with far-right and anti-LGBTQ views — also claimed to be “funded through a [US] Department of State … grant.” But Hovhannisyan wondered whether this was one absurd-sounding claim on the site that could actually be true. Rather than go after the fake information — which was easy, but which she knew would be like pushing against the ocean — she decided to chase the money.

She tried, unsuccessfully, to trace the grant through grants.gov (a US federal government grants site), and to find the owners of Medmedia.am and its controlling NGO through a search on the Whois site (which allows you to check the domain-owner of a particular site).

Then Hovhannisyan learned that some grant recipients have to apply for a DUNS number, which generates a unique numeric identifier, and complete a SAM (System for Award Management) registration process.

She searched the US SAM.gov database, and found a registration record for “Armenian Association of Young Doctors” — an NGO established by that same doctor. It took her yet another step to verify that the grant for this “Federal Assistance Award” was active.

Eight days after presenting her evidence, the US embassy to Armenia admitted that they had, in fact, funded both the NGO and the website.

A week after her story broke on openDemocracy, US Ambassador Lynne Tracy announced that the embassy would end its funding for the website, and would be “tightening up some procedures.”

The openDemocracy story has since been covered or cited in more than 70 media outlets, and in eight languages.

“I asked myself: how could the US State Department finance an Armenian website that spreads COVID-19 misinformation and advocates against vaccinations?” said Hovhannisyan. “Dangerous disinformation has been rampant during the COVID-19 pandemic. [This story’s] real-world impact exceeded our expectations.

“Medmedia appears to have changed its approach, and the number of posts with misleading and incorrect claims about COVID-19 seems to have decreased. This is the most important impact for me!”

Six Tools for Identifying Actors Behind COVID-19 Disinformation

- Hoaxy. This open-source tool allows you visualize the spread of posts and articles online, search articles from low-credibility sources, and plot the cumulative number of shares over time.

- CrowdTangle. Most disinformation sleuths describe CrowdTangle as the most powerful single tool in the field. The social media monitoring platform provides deep insights into how content is being shared across platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit.

- Graphika. This tool allows you to map the social media landscape, and find connections between domains. A complex but effective tool for visualizing misinformation flows in graphic form is Gephi.

- For investigations into financially-driven disinformation and scams, tools like DNSlytics.com can help you trace ads and suspicious commercial activities across sites. Premium accounts carry a small fee. For newsrooms with large investigative budgets, Adbeat is a tool that trawls the web and provides useful intelligence on display ads.

- Whopostedwhat. Created by online intelligence expert Henk van Ess, Whopostedwhat is a tool designed for public interest investigators that allows you to search Facebook for keywords by date. Along with the video verification tool InVID and CrowdTangle, it has emerged as a go-to tool for tracking the actors behind misleading social media posts.

- Google Search to find questions, rather than answers. Rinehart said typing half a question into Google, like “Why is the federal government …” supplies frequently searched questions that can give reporters a sense of what communities suspect, or don’t know, when consuming news. One famous example was the top trending Google question “What is the European Union” — widely asked by Britons the day after the UK’s Brexit vote.

Waves of Dangerous Falsehoods in Asia

Delhi-based Syed Nazakat, the president of the Society of Asian Journalists and a GIJN board member, said he had seen four waves of disinformation about the pandemic in Asia: first, about its origins, then unrelated stories from the past being posed as virus-related, then about cures, and finally about the lockdown.

Nazakat warned that the next wave — over the next few months — would likely see coordinated disinformation campaigns against the development of vaccines.

“I am telling you, I can see that coming, and it will be more coordinated and more intense than what we have seen,” he said. “That could hamper or sabotage any progress we might see with the development of vaccines, or people will avoid it because of these rumors. I’m talking about thousands of videos every day against vaccines. Reporters will have their hands full.”

Nazakat — who founded the collaborative, data-driven storytelling startup DataLEADS — said vaccine conspiracy theories exploded across Pakistan after major news stories stated that the CIA had staged a vaccination visit to Osama Bin Laden’s compound ahead of the US military raid on the al-Qaida leader in 2011. He said many of those concerns were now being exploited during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Even when the pandemic started happening, people said there is no COVID, it is a secret CIA mission,” he said. “We have seen a lot of videos in Hindi, and also Bangla, about alternative medicines and cures — like, how garlic or cow urine can cure you — and then we saw a lot of conspiracy theories in the Urdu language, which is widely spoken in Pakistan and also India. One reason for that was because of vaccines. COVID has also been used as a hate speech weapon against Muslims. And we have done almost a hundred stories on claims of ‘cures’ with no scientific evidence. When we investigated who was doing it, we saw a huge number of interest groups related to alternative medicine.”

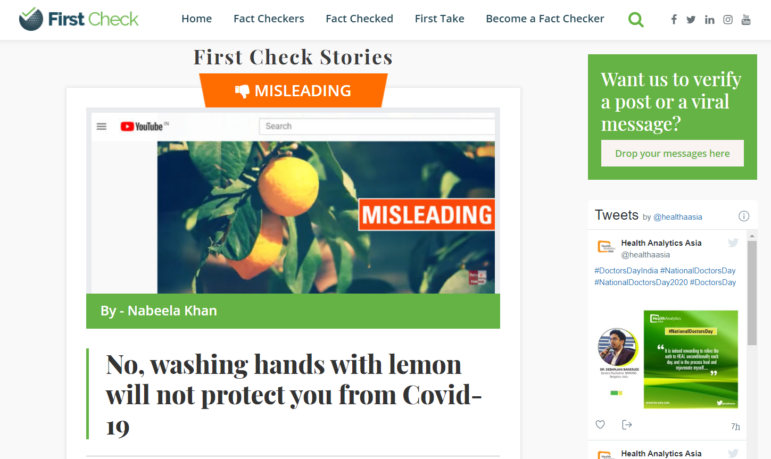

This story in HealthAnalyticsAsia — where a doctor quickly refuted a viral claim about the protective qualities of lemon juice — is just one example of the site’s pioneering partnership with a network of doctors throughout Asia to check medical claims on COVID-19 in real time. ScreenShot: Courtesy of HealthAnalyticsAsia.

In a pioneering program, Health Analytics Asia — a division of DataLEADS — has partnered with doctors in 17 Asian countries to conduct real-time checks of medical claims in pandemic-related posts and articles.

Exposing the Scammers behind the Hoaxes

Silverman has edited several books to help reporters tackle disinformation, including the free-to-download “Verification Handbook: A definitive guide to verifying digital content for emergency coverage.”

In May, Silverman looked into coordinated disinformation about anti-COVID-19 face masks on Facebook, and went on to discover a major price gouging scam that was not only ripping off customers, but also deceiving Facebook itself.

His reporting process on the story offers a blueprint for how reporters can uncover commercial disinformation networks and the scammers behind them from a single piece of red flag content.

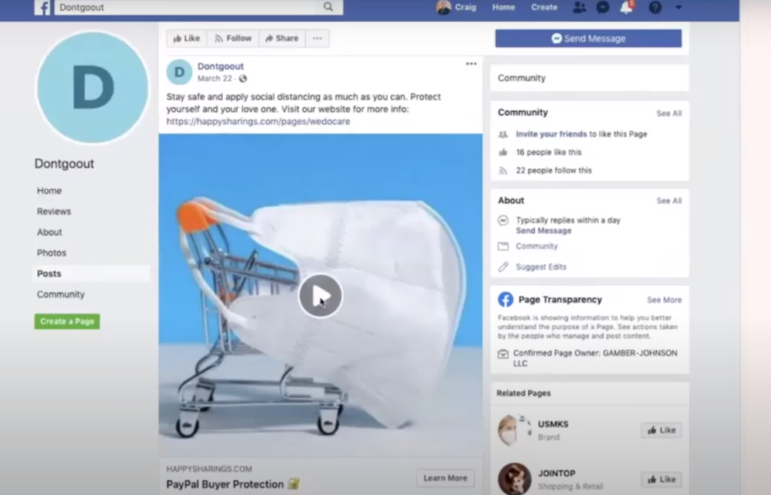

Craig Silverman’s investigation exposed a major scam network which began with a Facebook post. Screenshot

In a GIJN webinar on disinformation, Silverman explained that he had begun with a single Facebook ad for N95 masks that cited false statistics, and a quote from the “surgeon general” for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — a position that doesn’t exist.

While the URL link for the online store did not offer much information, Silverman simply put that URL in quotation marks and searched Google. This gave him all the pages Google had indexed about that URL, which included PayPal communities, complaints from scammed customers, and the name of the company that sold the masks: ZestAds. A separate search for “masks” and “ZestAds” found hundreds more complaints about false information and grossly overpriced face masks, or orders that never arrived.

After visiting the “related pages” section and all the sidebar elements on the original Facebook page — including “reviews” and “about” — to look for more comments, he clicked on the page’s Transparency box, and found a US company, rather than ZestAds, listed as the “confirmed page owner.”

For Silverman, this discrepancy was one of several red flags about the sales. Another was that the page manager for this supposedly American page was supposedly in Spain.

A Facebook group dedicated to complaints about the company offered copies of receipts — and these, in turn, offered URLs for the online stores set up by ZestAds.

Silverman then used a “snowballing” technique to investigate the scale of the network, including the number of Facebook pages and online stores selling the masks.

“What we’ve seen is a blossoming of companies selling products on Facebook using Shopify as their store, which they can [set up] in minutes, and continuing to create tons of them as they mislead people and steal their money,” he said.

Knowing that scammers often can’t be bothered to write different mission statements for each store, Silverman extracted sentences from the “About Us” pages of some of the online stores, put them in quotation marks, and searched on Google. He found almost 300 stores, and manually visited each of their sites — logging their details into a spreadsheet to see whether they were all connected to the scam network.

“This is where any glamour of the investigation goes away,” he remarked. “But the manual work is really important, because I really had a good feel for these stores and what they were doing because I saw them with my own eyes.”

He then used the search operator phrase “site:facebook.com” with the name of almost 200 companies linked to the network to map its penetration into social media.

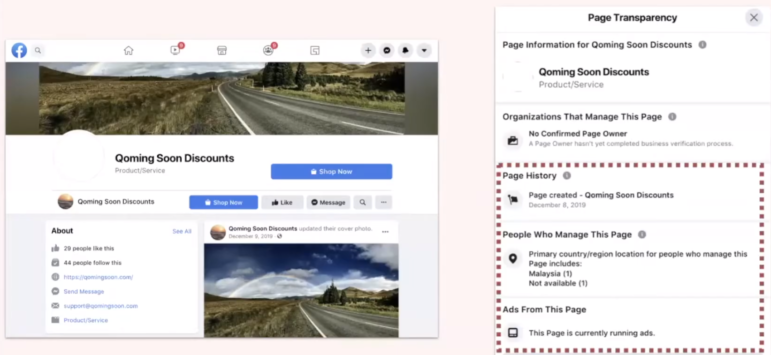

The Transparency box on the Facebook page for this store — one of almost 200 stores in the network — pointed Silverman to the company’s true location: Malaysia. Screenshot

This led him to a Facebook page for one online store, “qomingsoon.com,” whose Transparency function finally tipped him to the true location of the scam headquarters: a company in Malaysia.

“It turned out that ZestAds found a way to subvert Facebook’s process for adding a confirmed page owner, so they were actively misleading people, and actively exploiting Facebook,” he said.

Silverman then ran a search on Whois.net of the stores on DomainBigData.com to dig up their registration histories.

“At the time, Facebook had banned all mask ads,” said Silverman. “So not only were we exposing this company that was ripping people off with false information, we also revealed that Facebook was failing to enforce its own policy.”

BuzzFeed sent Facebook a list of almost 100 pages linked to Zest Ads. Facebook sent the company a cease and desist letter, and has since banned ZestAds from its platform.

Six Techniques for Tracking Down the People Behind Disinformation

- Find the earliest profile photo or background photo uploaded on the suspicious social media page you’re investigating. Then look at the “likes” and comments attached. Often, people close to the page owner — or even the owner themselves — are the first to “like” or engage with the earliest images.

- Information is slightly different between the old and new Facebook page design, so switch between these two formats to see whether there is more useful data or links on the alternate format. Look for receipts in Facebook groups where consumers gather to complain about products.

- When seeking to contact trolls directly — and learn the motivation behind their actions — it’s important to reveal yourself as a reporter. However, some journalists have found that trolls are far more likely to agree to interviews when the approach focuses on the popularity of their pages, rather than the false content. “Don’t lie about your intentions, but [trolls] do like to talk about popularity,” noted Capron.

- Place “About Us” content on suspected scam websites in quotations, and search to see whether other stores have been set up with the same backstory in the network. Use the quotation marks operator for URLs and domains as well — as in “site:youtube.com”.

- Identify possible disinformation by red flags in the content, including emotional or extreme language, and breathless appeals, such as: “Read this important news before Twitter removes it.” Identical structures in newsfeed posts is another indicator. Pay attention to sites with “.news” domains, as disinformation networks sometimes use these to silo audiences with different ideological views.

- Avoid amplifying the false messages or the extremist brands you’re investigating. First Draft’s Aimee Rinehart suggests that stories on disinformation by a conspiracy theorist group like QAnon exclude the word “QAnon” from its headline and first three sentences, to lessen the chance that it might be amplified as a trending term. Silverman suggests that these stories should ideally begin with the true facts, followed by a careful description of the falsehood — and that the verified facts be repeated near the end to reinforce the truth in readers’ memories. “Hold the trolls accountable without giving them the notoriety they want,” he said.

Untangling Disinformation Empires

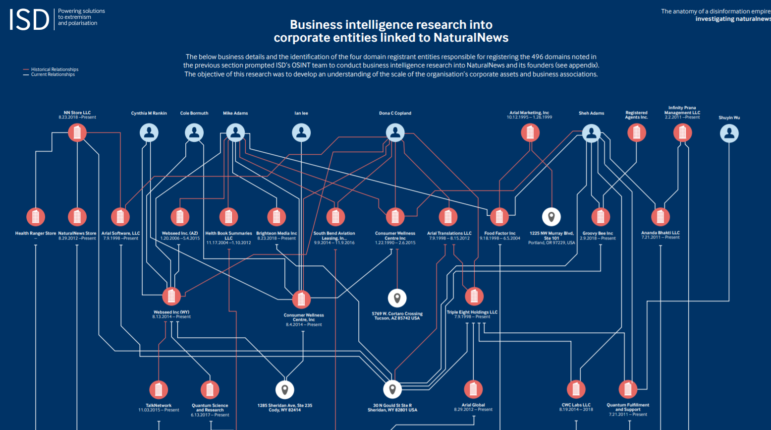

In June, the UK-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) — an anti-extremism civil society organization that works with journalists — published a comprehensive investigation into one of the world’s largest contributors to COVID-19 disinformation.

Its investigation found 496 domains still linked to the far-right, US-based Natural News network and its founder, Mike Adams, despite the banning of that core domain from various social media platforms, including Facebook in June 2019.

The propaganda network generated numerous false conspiracy stories on topics like Bill Gates and 5G towers, and was a “super spreader” of the fake “Plandemic” conspiracy video which promoted the false claim that the pandemic was planned.

Investigators at ISD compiled this spiderweb map of domain owners and commercial entities linked to the vast Natural News COVID-19 disinformation network. Image: Courtesy of ISD

ISD’s report stated that: “Despite being banned from Facebook in 2019 and again in 2020, Natural News and its affiliated domains are used to share disinformation on a variety of topics including COVID-19 and the George Floyd protests.” Researchers found 562,193 interactions on posts relating to Natural News domains in less than three months in 2020, after that ban.

“Attribution, and tracing back to the perpetrators, is the missing piece in a lot of work in disinformation, because it is absolutely the hardest to do,” said Chloe Colliver, head of the Digital Research Unit at ISD. “It requires a set of skills and courage to reveal what are often quite nefarious characters. It is important to reveal to the public that this isn’t just an uncontrollable phenomenon. There are power dynamics that are important for journalists to investigate.”

Colliver said CrowdTangle, Gephi, and Bellingcat’s list of OSINT tools had proved important for investigating complex networks. ISD researchers also used Google Earth Pro to see if Natural News-related online addresses were linked to brick-and-mortar offices.

One key tip for journalists that emerged from this investigation was that some of the largest ideological disinformation networks take care to divide their audiences ideologically, and funnel them into sites that exclude content that might upset them.

For instance, investigators found that audiences interested in holistic health — and deemed likely to be alienated by gun rights content — were redirected to “.news” domain sites with misleading alternative health claims, but without pro-gun propaganda.

Disinformation Areas to Watch

Colliver said “dark PR,” where firms are hired to discredit individuals and institutions, including news media, with strategically placed falsehoods, should be an area of scrutiny for investigative newsrooms in the coming months.

“I do think that the dark PR market is massively under-researched, and probably has a huge role in doing the dirty work of those seeking to do harm through COVID-19 disinformation,” she said.

“I suspect there is more to be found around what China has been doing in terms of its disinformation efforts around the world,” said BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman. “There are probably financial driven people around the world who are trying to make serious money from this in ways we’ve yet to uncover. The big element of coordination we’re already seeing is how the QAnon conspiracy community, and the anti-vaccine community, and anti-government extremists have formed an unholy alliance around the pandemic, where they are together pushing against wearing masks, and seeding conspiratorial narratives about it being a planned event,” he added.

Alexandre Capron, the reporter at France 24, said the 20-year-old hoax page administrator he interviewed was oblivious to the harm his 37 COVID-19-related “news” posts could have caused to its audience.

One falsely claimed that the World Health Organization had endorsed a Madagascan herbal remedy as a cure for COVID-19, and another centered around a fake, anti-vaccination quote attributed to prominent French epidemiologist Didier Raoult.

The student was candid about his disinformation plan and also the strange goal of the game. “Our strategy is to share these posts in several [major] groups,” he told Capron. “Our goal is to share news so that it actually happens.”

“His campaign was so popular because it played to Western resentments in the Congo diaspora, and the stories were always something people wanted to believe,” said Capron. “These guys were very young, but very smart, and they understand social media and what people want to read, and that’s all it takes.”

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.