Paul Myers, online sleuth extraordinaire, presented GIJN’s latest webinar. Photo: Nina Weymann-Schulz / GIJN

In late May 2020, a senior advisor to the British government publicly claimed to have issued a written warning about the danger of coronaviruses in 2019.

Seemingly clear evidence for this warning, including the word “coronavirus,” was visible in a blog the advisor had written on March 4, 2019.

But an investigation by the BBC showed that the word “coronavirus” was not written in the original blog post, and that the warning did not appear in the piece at all until at least April 9, 2020, when the pandemic was already in full swing.

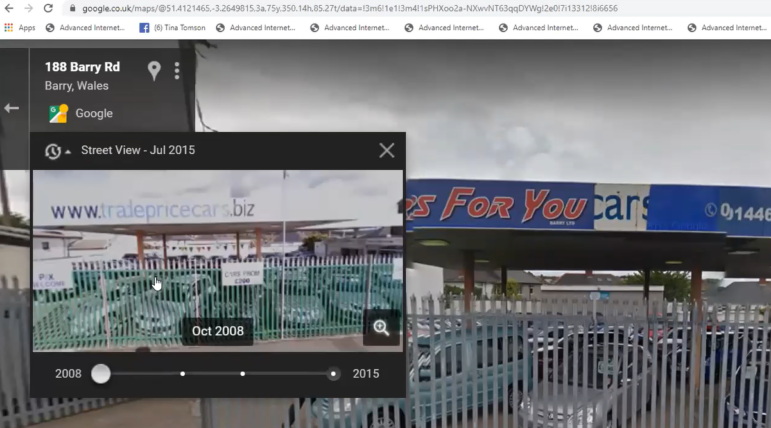

Paul Myers, the BBC’s lead internet research expert, says there are now many effective tools and techniques to help reporters dig into the digital past, including the Wayback Machine that revealed the advisor’s post-edited blog warning. Another, in Google Street View, allows reporters to “walk around” a scene in the past.

In last week’s online masterclass, presented to more than 700 journalists from 94 countries, Myers described the open source tools, syntax tricks, and search techniques to unearth elusive content, images, and social media posts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The event was the tenth in GIJN’s webinar series Investigating the Pandemic.

Unlike most of our webinars on the pandemic, which are available on GIJN’s YouTube channel, for proprietary reasons we were unable to record this session. But we’ve gathered some of the most powerful easy-to-use takeaways — simple, little-known syntax tricks for ordinary Google and Twitter searches, rather than the advanced or subscription-based search tools which you can find out more about in the GIJN archive or on Meyer’s own website, Research Clinic.

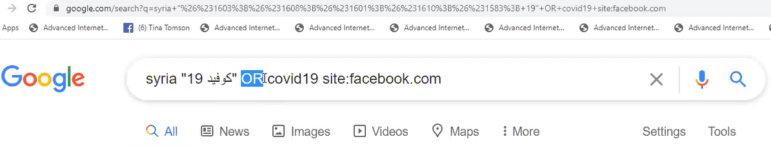

How many reporters already knew, for instance, that placing quotation marks around a single word — or a simple minus sign ahead of an unwanted subject — could eliminate mountains of unwanted results? Or that the word “OR”, in capital letters, can prevent you from accidentally ruining your search? Or that the prefix “site:” limits the search to the domain you care about?

Myers — who is currently head of the BBC Academy’s Investigations Support project — also invited journalists to think about how social media platforms are used in reality. So, while Instagram has poor search functionality, for instance, its largely younger users are more likely to tag their location than other social media users, making work-arounds into Instagram worthwhile for reporters seeking people on the scene at news events. He encouraged journalists to “tune in” to communities by using word clouds to find hashtags that only those communities use.

While he mentioned more than a dozen tools during the 90 minute session — and has described many more in prior presentations with GIJN — Myers emphasized that search-minded thinking represented the fundamental asset for online intelligence research.

“Most people search Google with natural language — they treat it as a person,” he says. “That can work well. But sometimes it will totally misunderstand your question, so I think it’s much better to control Google with logic and special tools.

“Google does not know what we want. To do an effective search, you need a strategy and the right key words. It’s easy to search, but hard to find stuff. Every time you do a search, as a matter of principle, look at how many results you’ve got. If too many, you need more detail.”

To illustrate the logical mindset, Myers offered the example of a search for comparisons of famous assassinations. Entering the search terms “Kennedy” and “Lennon” — meaning John F. Kennedy and John Lennon — triggers a slew of results, including the site for a British football team. But add the word “Caesar” and the search is suddenly focused only on assassination comparisons, because, Myers explained, “Why else would those three words be on the same page? Logic has steered our search and given different qualities to our results”.

Meanwhile, when searching for individuals on social media, a minute’s logical thought should start a search for a teenager on platforms like TikTok or Instagram, rather than LinkedIn, and the opposite for the CEO of a large company. And, with Twitter, it’s more effective to search for words users are more likely to use because of the character limits — like “info” rather than “information.”

Here’s a quick tour of the trove of tips and tools that Myers shared with the crowd:

Tips for Using Search Engines

-

- Remember that Google doesn’t see everything on the web, and makes copies of webpages that it does see. Some pages are hidden behind paywalls, while others are hidden in robots.txt pages;

- Don’t search for what you want. Instead, search for the words the webpage or social media post is more likely to feature;

- Focus your search by either using quotation marks around single words — which instructs Google to not look for synonyms — or adding a minus sign before a term that leads to unwanted categories;

- You can add flexibility, and avoid ruining a search, by adding the word “OR” in capital letters, between options

- When needed, you can focus your search to a particular domain with the prefix “site:”, leaving no space afterward:

- Explore Google’s tabs, tools, and advanced search functions, including date ranges;

- Work out the definite words first, and then the “maybe” words;

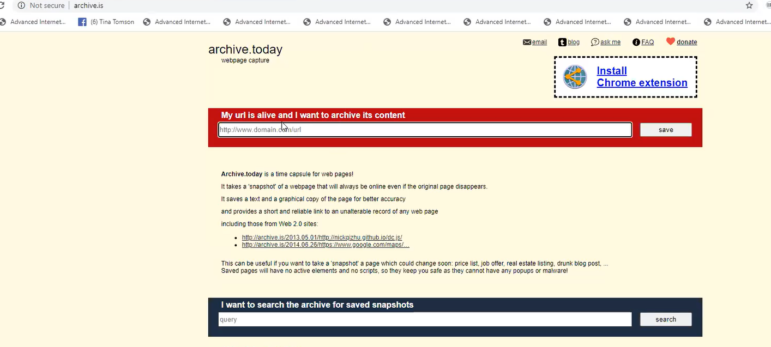

- Look for deleted pages – especially social media posts – on archive.org and archive.is:

- The phrase ext:pdf looks for pdf files. When searching for deleted documents, look for cached versions. If you know a few words that were in that document, put them in quotes in Google, and see if there are any other sources for the same document.

- Bing can do some things that Google can’t do. Myers says it “allows a bird’s eye view — it allows you to see over fences.” It allows you to search by IP address, rather than domain name, which, Myers says, “is useful if there are 50 different domain names on the same computer. [But] we really do have amazing tools at our disposal for search, using Google.”

Tips for Searching Social Media

- Although you can search from outside specific social media platforms, start your internal search boxes on a specific platforms; it has direct connections to its own database, and can offer more up-to-date results;

- When searching for individuals, try first to identify their email address. In addition to offering its own clues, email addresses are unique identifiers that often double as usernames, and can be used effectively by people-finding databases like Pipl.com.

- Enter a company name into email-format.com, and it will likely give you the corporate format for a target person’s email address. You can then work out their individual address from their name;

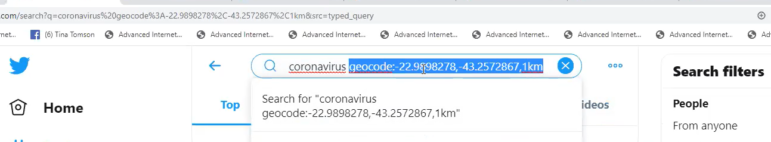

- Use the longitude and latitude figures automatically generated in online maps to find out what people in a particular neighborhood are saying about a particular subject. Copy those numbers across to Twitter, and add them (without a space) to the prefix ”geocode:”. Then add the radius you need to the end of the numbers string — for instance, “1km” (one kilometer).

- Search Youtube first via Google, by entering site:youtube.com, or by searching in its video tab;

- Embrace the sometimes odd preferences of each platform. For instance, successful searches of Instagram tend to feature underscores and compounded words, rather than hyphens. And while images cannot be copied from Instagram, they do offer meta information that can be used for onward search;

- Picbabun is one of the sites that offer effective searches of Instagram. It allows Instagram images to be copied and opened at full size;

- Echosec – a site friendly to journalists – will find Instagram posts sent via Twitter, where search functions are much better;

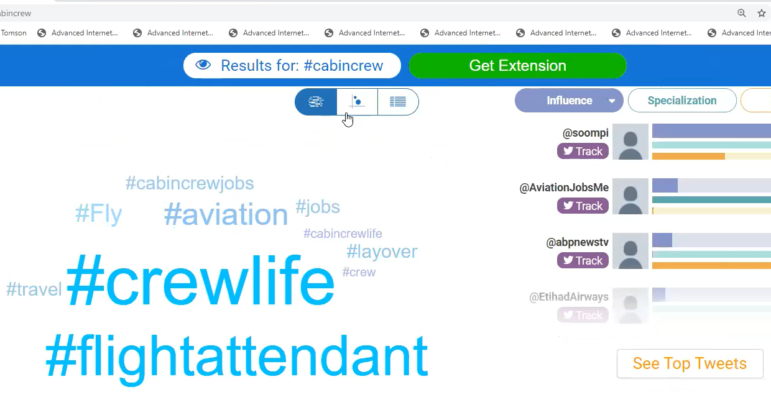

- Tune in to Twitter communities by identifying the hashtags that only those communities use. Identify those hashtags from word clouds on Hashtagify.me. A search of hashtags used by airline cabin crew, for example, reveals that #crewlife is a major hashtag for this community. Plugged back into Twitter, that term immediately reveals posts by airline personnel.

- The prefix “intitle:” finds words in the title of posts across social media;

- If you have a hunch that someone has post-edited something on Facebook, click on the three little dots to the top right, see ‘edit history’, and you’ll be able to see previous versions;

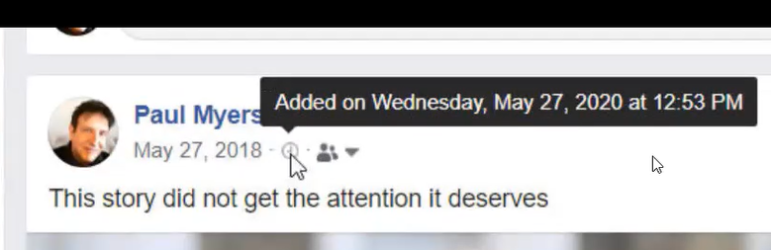

- If you suspect that an entire post has been moved back into the past, hover your cursor over the small clock icon next to the Facebook post, which will reveal the date it was added:

- Find Twitter posts with links to other sites using the prefix “url:” — so you could find people referencing their sale of face masks on Amazon, for instance, with url:amazon;

- Followerwonk allows you to search people’s biographies in Twitter, but also finds mutual followers of two different accounts;

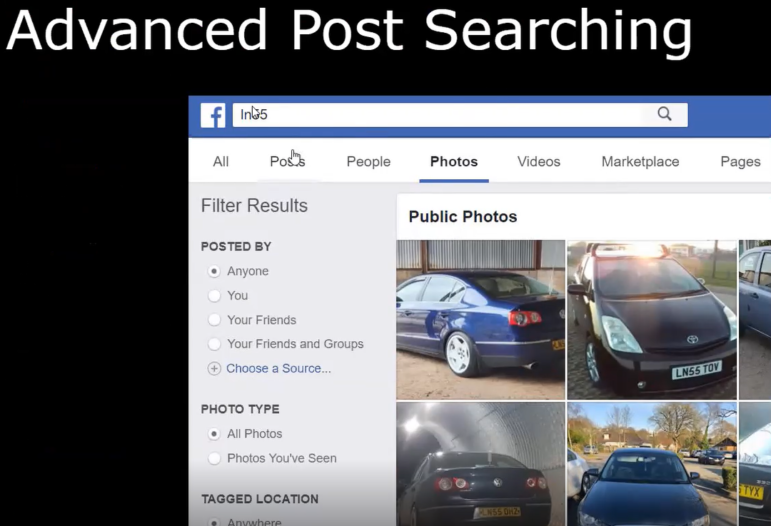

- While Facebook’s search function is awkward, it does allow searches by any key words, including company names, so you can search for a person without initially knowing their name;

- Facebook also reads words and numbers embedded in uploaded images, so even car registration numbers are potentially searchable:

- Sites offering reliable advanced search of Facebook include FBsearch and Graph.tips;

- When limited by ”most relevant” filters, search Google for solutions under “avoiding the filter bubble.” To tackle the problem in Facebook, set up an account with no friends and no biographical information, clear your cookies, and you should avoid much of the profiling;

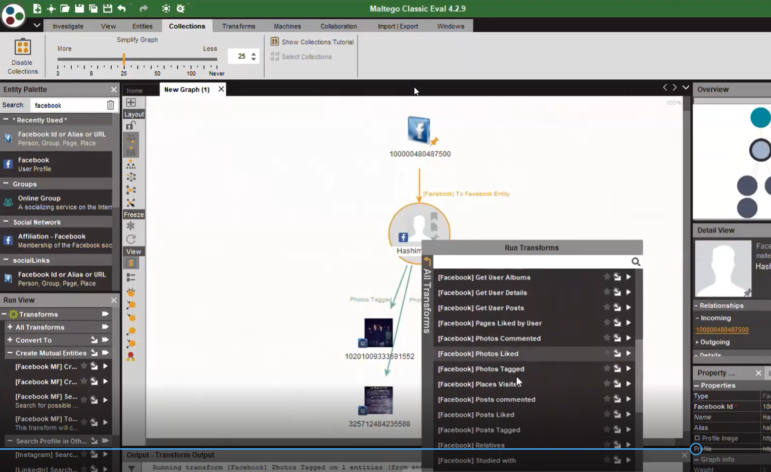

- One highly advanced — but fee-based — search site is Social Links, which works within the Maltego program. Myers says: “It does cost money. But I’ve done so many things with this. You can do facial recognition searches across different social networks; searches for posts tagged or photos tagged. [Many reporters] were disappointed by Facebook’s decision to cancel our ability to use its Graph Search function. [But] all the things you used to be able to do with Graph Search, you can now do with a copy of Maltego and with Social Links running on it.”

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.