Editor’s note: Paul Bradshaw, who runs the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism and MA in Data Journalism courses at Birmingham City University, shared these tips with his students on how to use public documents for story leads and ideas. While they focus on companies registered in the United Kingdom, most of the concepts and formats apply to other jurisdictions, as well.

Here are just nine ways to find stories in company accounts — and most of them don’t involve any numbers at all.

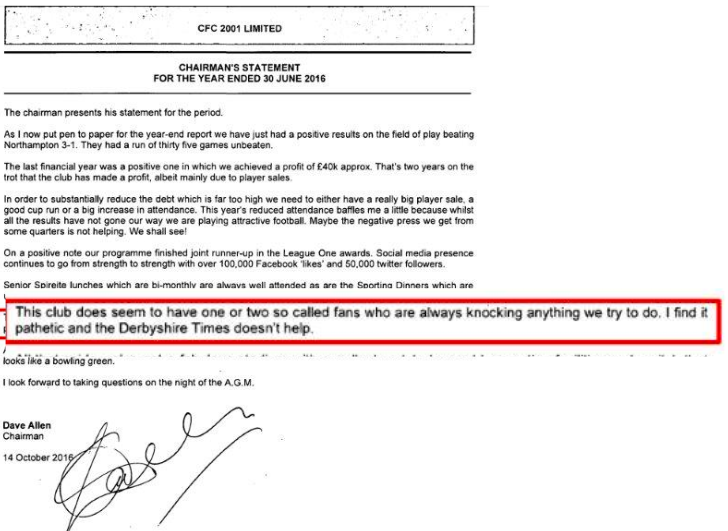

1. The Controversial Director’s Statement

Director’s statements tend to be quite dry, vague pieces of writing — but occasionally, a director lets loose or shares something newsworthy. Here, for example, is the chairman of a football club criticizing “so called fans” [sic] — as well as the local newspaper for good measure.

Once you see something like that, it’s normally straight on the phone for a reaction and then a response from the organization involved.

2. The Conflict of Interest

One of the first places I look in any company’s accounts is the very last page: this is where the company declares any payments to related parties.

Last year, for example, I noticed that a homelessness charity had taken out an £85,000 (around $105,000) bond which was being used to finance the building of care homes by a company owned by one of the charity’s trustees. What’s more, the trustee was also a director of the company selling the bonds (which was not declared in the accounts).

This simple fact can provide the basis for organizing some interviews to ask some basic questions — which led to two stories by The Bolton News’ Joseph Timan: one where the charity defended the move; and a second based on a response from the Charity Commission.

Note that the story here is often not (at first) conflict of interest itself (which is vague and complex) but the reaction and action following it being revealed to others.

3. “This Place Is in Trouble”

A story in The Guardian about a company with “material uncertainties” over its future. Screenshot

Before you get to the numbers in the accounts (more on that below) you will have a statement from the accountants on the company as a “going concern.”

If the accountants have any doubts over the company’s ability to stay in business in the next year, this is where you’ll find them. Specifically, you are looking for the phrases “emphasis of matter” or “material uncertainty.”

The emphasis of matter often outlines what factors have led to a material uncertainty that the company can continue to operate.

It might be that some big debts have to be paid this year and there’s not enough coming in to pay for it — or that certain factors could reduce income enough to leave them unable to pay for costs (including loans).

Before it finally collapsed into administration, for example, the care home operator Four Seasons released accounts which identified Brexit-related staffing challenges, and low bed occupancy (profits) due to higher than expected winter deaths as two key factors causing doubts over their ability to continue operating.

If accounts are delayed it is sometimes an indication that they are busy trying to avoid admitting these concerns — for example securing an extension on loans or getting rid of loss-making parts of the company.

4. “Celebrity” Profits

A story in The Irish Times about the revenues of the author of Fifty Shades of Grey. The “celebrity” nature of the company makes the story more newsworthy. Screenshot

So far we’ve avoided the numbers, but it doesn’t take a lot of work to see stories in some of the most basic numbers in a company’s accounts.

The cash flow page — normally the first page of numbers to appear — contains, among other things, a company’s profits for the year covered by the accounts, as well as the previous year.

Note that numbers in brackets indicate negative numbers — in other words a loss, not profit.

You should be able to tell at a glance whether that profit is going up or down. And a simple sum (change divided by the previous year’s profits) will tell you how much that change is in percentage terms. You can even use an online tool to calculate the change for you.

5. How Much Tax Didn’t They Pay?

The Telegraph were one of many outlets to report on Facebook’s small tax bill in 2019. Screenshot

Establishing tax avoidance or evasion is going to take more than just looking at a company’s accounts — but you can report on just how little tax an apparently successful company is paying in the United Kingdom, and the reaction to that new information.

Facebook UK, for example (the British arm of the American firm), declared a surprisingly low tax payment in 2018 — £28m (around $34.6 million) when the company was declaring revenue of more than 28 times that amount. The reason? Mainly vague “administrative expenses” which mean the profit on that revenue is massively reduced.

The stories on that small tax bill, then, focus largely on response to the figures from politicians, tax experts, and campaigners who argue that they should be paying more and/or express concern that those “administrative expenses” might be a way of extracting money out of the UK to another Facebook company in a different country.

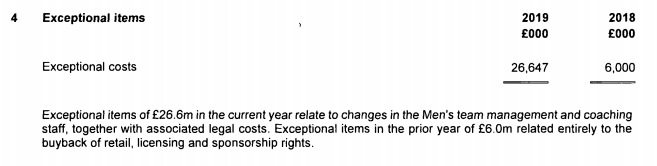

6. Pay-offs and Other Newsworthy Admissions

The notes to the accounts can contain all sorts of events during the year that might be stories in themselves.

Chelsea Football Club’s pay-off of manager Antonio Conte, for example, comes in Note 4 of the 2019 accounts, labeled “exceptional items.”

And News Group’s payments to settle phone hacking cases also comes in Note 4 of their accounts for 2019, as “operating one-off charges.”

The notes won’t always be obvious. Conte’s sacking is described as relating to “changes in the Men’s team management and coaching staff, together with associated legal costs” — so some background knowledge of what’s been going on in the last year (and some forward planning to check the accounts when they come out to see how much a sacking cost) is useful.

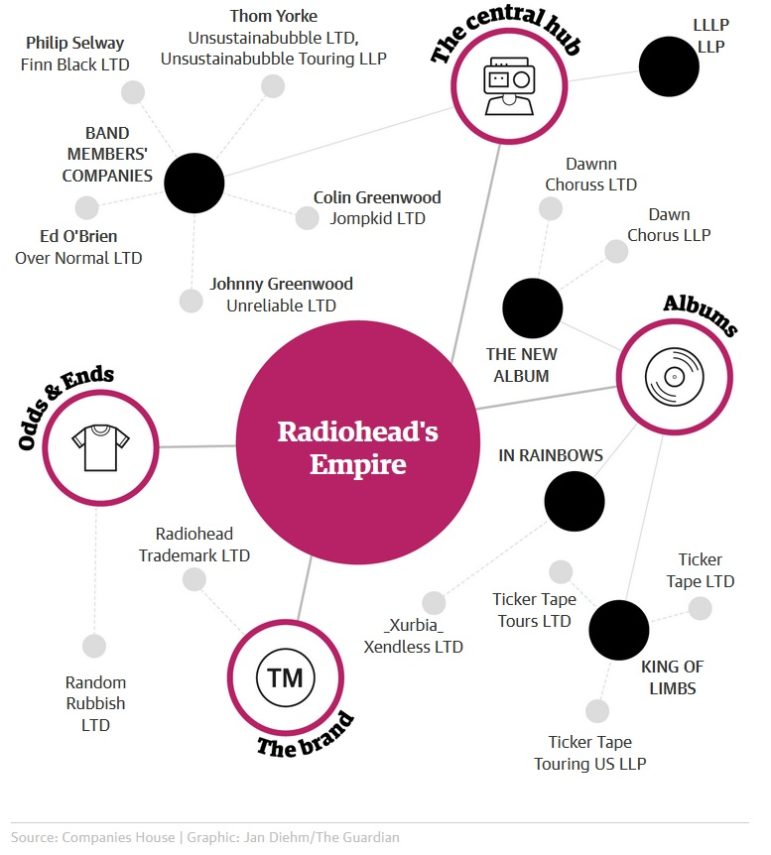

7. The “Exploring the Corporate Empire of…” Story

Company accounts will often list subsidiaries of a company (a whole list might even be provided), or mention sister companies.

Look for the “ultimate parent company” section near the end of the accounts that lists who ultimately controls this company (sometimes through a number of other parent companies).

Better still, in the UK you can use Companies House to look at the officers of a company, and the other companies that they are directors of: If there are connected companies the directors are often directors of those companies too, and often companies themselves are listed as directors.

From The Guardian: Radiohead’s corporate empire: inside the band’s dollars and cents. Graphic by Jan Diehm. Screenshot

Mapping the network of connections between companies and directors can be a story in itself, especially if you can draw a neat network diagram showing those connections. It can also be a useful backgrounder if a company is thrust into the spotlight — BuzzFeed’s Inside the Complex Snarl of Companies that Control the Pro-Corbyn Momentum Campaign, for example, or, in the wake of the collapse of British construction company Carillion, a story on how many linked companies are registered in the local area, by one of my MA Data Journalism students.

8. Problems, Risks, and Concerns

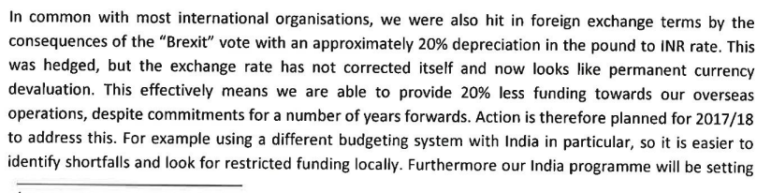

Organizations will sometimes highlight risks in their field which are causing concern. These accounts on the Charity Commission website for leprosy charity Lepra, for example, highlight (in a strategic report section) the effect of Brexit on exchange rates and reduced value of donations — donations will now not go as far as they used to.

An extract from Lepra’s accounts showing concerns. Screenshot

When you find a concern like this, a follow-up phone call to the organization concerned to flesh out their statement may give you a decent story — but if it’s likely to affect other organizations in the sector (in this example, charities raising money in the UK to spend overseas) then it’s worth calling others likely to have the same problem, too. That turns it from one organization’s concerns to a problem affecting a whole sector.

9. You Earn How Much?

The Guardian’s reporting on the pay package of the chief executive of British energy supplier Centrica. Screenshot

Executive pay is regularly on the news agenda, so look out for “directors remuneration” — especially big changes year-to-year.

This information is only available in larger companies’ accounts — and if they’re a listed company then they’ll provide even more information still. The Centrica accounts (PDF) for The Guardian’s story on executive pay, for example, includes a whole “remuneration report” section while Sainsbury’s publish theirs as a standalone document.

If they provide the information you might also look to see whether average pay in an organization is changing at the same rate, and whether employee numbers and/or total pay are being cut.

Another tip with listed companies is to search for the annual reports not just on Companies House but on the official website too — often the version on their website can be searched, whereas the Companies House version is usually scanned and so cannot be searched.

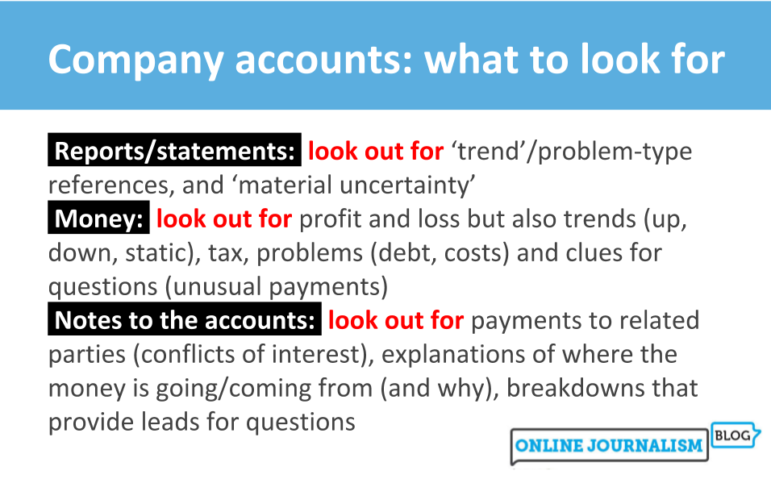

Those are just nine techniques (a few more are in the image below).

This story was first published on Paul Bradshaw’s Online Journalism Blog and is reproduced here with permission. If you use these techniques in any of your reporting, he welcomes you to write him on Twitter @paulbradshaw.

Paul Bradshaw runs the MA in Data Journalism and the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism at Birmingham City University and is the author of a number of books and book chapters about online journalism and the internet, including the Online Journalism Handbook, Finding Stories in Spreadsheets, Data Journalism Heist, and Scraping for Journalists.

Paul Bradshaw runs the MA in Data Journalism and the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism at Birmingham City University and is the author of a number of books and book chapters about online journalism and the internet, including the Online Journalism Handbook, Finding Stories in Spreadsheets, Data Journalism Heist, and Scraping for Journalists.