Editor’s note: Since this interview was originally published in February, the global coronavirus pandemic has shed further light on how location tracking data is collected and the potential risks of how it’s used. Google is releasing aggregated location data reports to show how people’s movement patterns are changing around the world, while privacy advocates are sounding the alarm about governments’ efforts to obtain more location data from telecom companies.

A phone application company you have never heard of before likely knows where you are right now. That information is being bought and sold right now. Those apps and their partners have joined a lucrative industry at the expense of the privacy of smartphone users. It’s an issue of national security, and it’s virtually unregulated.

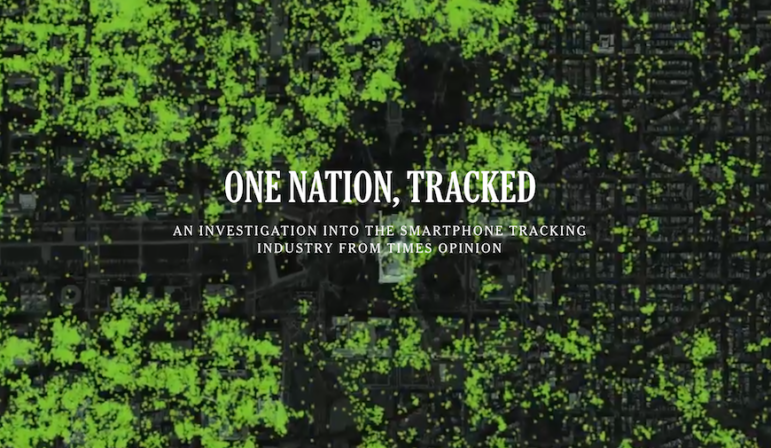

The New York Times’ Privacy Project is directing attention to this issue. In Twelve Million Phones, One Dataset, Zero Privacy, Stuart A. Thompson and Charlie Warzel visualize phones as dots being tracked around the country, from the Pentagon and the White House to the streets of San Francisco.

Storybench spoke with Warzel, a writer-at-large for the Times’ Opinion section, and Thompson, the head of Opinion’s visual journalism department, about why they chose to create these visualizations and the challenges that arose in constructing this data-driven, yet very human, story.

The article opens up to a visualization of blinking dots on a map of different buildings. It looks like it should be in a spy film. Why did you decide to make this the first thing people see?

Stuart A. Thompson: So, the Times had approached this topic one year prior with a news piece and this is building on the foundation of that. We never really had a good sense of scale for how much data there is. The data that we had was of several cities and super dense and covered everything. And we wanted to give people that visceral reaction. It’s not one person or some strangers. It’s everything everywhere. And we had that idea really early on to do a zoom-out of a city and the idea was to start at one dot and keep going, and going, and going, and it would never end. I think that was the idea, to have an emotional connection to something you never get to see.

Charlie Warzel: It is really hard to wrap your mind around how much information is out there, how many phones, and how much is being sent. I think this is one of those stories that had a lot of the words before the visuals were on the page. As soon as I saw what Stuart had made, I was like: “We don’t even really need the words. The visuals tell the story better.”

Did you specifically ask to have these graphics rather than have a picture or video?

Thompson: The way that newsrooms used to be set up, and a lot of them still are, is you have reporters doing interviews and writing text and you have a bunch of graphics people making bar charts who sometimes do more visual stuff. They’re sort of just sitting in the corner of some dark closet in the newsroom (laughs). The Times for the past decade has been trying to marry those two things closer together and that’s the origin of the team that I run, which is the visual journalism team in Opinion.

Rather than making visuals like the window dressing on a nicely reported piece, let’s find the stories and tell the stories that you can’t tell without visuals or can’t tell nearly as well. Like you could probably write this story without any visuals and it would be a good story that people would read, but the impact really comes from seeing it all together. They’re not separate things.

A reporter might think of a headline while they’re writing and we might think of the visual that we want to lead the piece because that affects what is written. In the first text-only drafts of the piece, it had bubble points for that stat and little annotations around it so editors will know what we’re trying to do there. We show them that you have to imagine this idea with these images. Whether it is a video or it’s animated that it is for additional flair but it does pull you in a little bit more gradually.

Could you walk us through how you were introduced to this story and your research process?

Thompson: So the Privacy Project, which is a year-long look at privacy and technology, approached us with the data and they were worried about the implications. They thought it could use someone with a voice to argue for change. We went out to learn about an industry that’s pretty opaque and hard to understand because it’s totally invisible. When you’re on your phone, you can’t see what’s going on. A lot of the business deals are not announced publicly. The connections between different companies and what they do with the data … none of that stuff is that well exposed. It was a huge research undertaking and there was a lot of data work.

Warzel: This is one of those situations where the data led everything. It was the story, and a lot of the reporting was either to confirm things or get more contact for things in the data. This was sort of an interesting reporting process because a lot of the times you’re going and calling up people or going to visit people. We went to Pasadena for one story. It was an inversion of the general reporting process.

Usually you go to people and are like, “Please tell me this thing. I need to know information.” And we actually had all the information and we’re asking people to see it. It was sort of a weird mode. It was data driven in the sense that the data helped provide so much for those visuals, but it was also in the sense that it was giving us leads and anecdotes. The reporting was just trying to run that down and make sure it made sense or it was accurate.

Did you know at the start from looking at the data how you wanted to organize the story? Was it when you started to talk to people that it took form?

Warzel: Before we started talking to people we found in the data, we had the outline of the story. We made our outline based on our research of companies who promote assumptions. We had problems with that. One assumption was that the data is anonymous, and we felt pretty comfortable saying that it was not. [The companies say] it is really hard to keep this data anonymous and secure, and we obviously had the data so how could it be secure?

We had [the data on] Washington, so we knew that national security would be part of our series. It ended up being the second story of the seven. I think we had a pretty good sense of the parameters of it. That Pasadena story didn’t come until pretty late. Only a couple weeks before. We had stories in the main pieces about the people we had, but it seems like there was a little more to say when you isolate a region … The first stories were big high-level stories about business and the industry and the national security apparatus. The data is also a story of communities, and towns, and people living their lives, going to Best Buy and church. There was enough there that we could make a full story out of that. We wanted to zero-in on an area where there was a mix of different stories to tell.

Screenshot: The New York Times

Was there a situation where someone didn’t want anything to do with this story? How did you handle that?

Warzel: That was a major thing in this. It was actually another reason to go to Pasadena. Originally, we didn’t know how many stories it was going to be, but we identified a lot of people through this and wanted to do the due diligence of contacting them and just getting them to talk about the experience of being in this data set. It was people we found at political rallies, people who might have been in government, a whole slew of people who were relatively famous to those with no public profile. Not a lot of people wanted to talk.

A lot of people thought it was maybe like a scam. You’d think coming from a Times’ email address, the whole premise of it sounded kind of outrageous. Like, “We have reason to believe we’ve tracked all your movements. We work for The New York Times.” And a lot of people were like, “Is this an email scam?” Or people [believed they were being] phished. I think that’s part of the reason we zeroed in on a neighborhood and put ourselves to the ground and do the work of knocking on doors of people cold and had that awkward interaction of explaining.

There were people on the ground who didn’t want to talk. There were people in religious organizations or other community organizations who felt vulnerable and didn’t want to talk to the piece. When we were able to show certain people what we had, and communicate what the project was about and it had this advocacy about it, there were a lot more people who were interested.

You included the companies who use data collection, as well as their logos, in the piece. Is that a definitive choice you felt you needed to do?

Thompson: We talked about that quite a bit. I thought it was really important that companies are identified because, for one reason, is that they operate pretty much behind the scenes. They’re literally hidden in the apps you download. I’ve identified like 80 companies that were working around this. We had to feel comfortable with the ones that we include and make sure it was fair, because companies that work around the industry might not engage with what we are talking about in the story. [They] might have other priorities and might have a smaller part in the business, so we ended up plucking the ones we felt most comfortable with.

Warzel: I was a little more on the outside of that process until we got to this point of needing to talk about it, who we wanted, who needed to be in there, sort of talking to the companies and needing to vet them. That was maybe one of the most frustrating parts of the reporting because it really did highlight just how opaque the advertising industry is and the ways they manipulate language in order to shield themselves.

There were a number of companies that, when you contact them and tell them they’re going to be identified in a mobile data location space, they say no, we don’t do that…instead, they say they track some sort of customer journey path. They change the words around so they don’t fit into the category, but it’s effectively the same thing. It’s very difficult because it is so technological. It is so nuanced and varied. A normal consumer doesn’t stand a chance when it comes to that decision.

Photo: The New York Times

Because this process was so frustrating, especially with these companies saying what they did, were there any statements you were careful not to make?

Thompson: The other reason we wanted to identify apps is because when you see a bunch of names, they’re all these weird companies. It’s like, “Wait, these are the ones that have my locations?” It’s not like Google, where we understand that they have everything. It’s more like a startup that you don’t know about. We were careful around apps. It’s tough to talk about apps and companies without isolating one. You want to include everything. That’s what people want to know. When we publish this story it’s like, “Okay, what apps do I need to delete?” And it’s really hard to say. That’s part of the whole system. It’s hard to know what they’re doing.

I talked to Foursquare and brought the CEO a list of apps that were receiving locations and how they were disclosing that to people. He said they do get locations, but you know it’s like we can do it under this specific contact and we don’t use it. We keep it briefly and we throw it out … You have to be really careful reporting the industry because it is so complicated and the companies are so adept. The whole basis of their business is to be confusing to people. That’s part of it: the misdirection that goes on with privacy policies and disclosure screens. They control all the language and they try to make it as finely tuned as they can to get everything they want out of it. Overall, it’s a good idea to be careful about how we talk about companies and what they do and feel comfortable it can be understood totally.

Did that influence why it was published in the Opinion’s section?

Warzel: The sources came to the Opinions section because of the Privacy Project and the ongoing work we were doing in this space. Also, because there was a genuine worry about this information, a desire to advocate for change, and pressure lawmakers, tech companies, and the advertising industry to feel the need that there is something wrong here that needs to be addressed urgently. That is the type of work the Opinion section is well suited for.

Sometimes a newsroom is constrained by that lack of opinionated journalism: “You need to decide for yourself what do think about this.” But our piece didn’t do that. It said that we want you to know this is the argument. This is out of control, this is invasive, this needs to change. And in a couple of ways the final piece we publish in the series is an editorial by the editorial board at The New York Times that argues explicitly that lawmakers need to do something.

Americans didn’t sign up for this, and a federal privacy law is needed. That’s just something that a traditional newsroom is not going to be comfortable doing necessarily, and I think all the rigor of reporting, all of the vetting, all the careful use of language and responsibility… that’s the Times’ standard of reporting and fairness. Our ability to advocate as well was the real reason why they came to us to do it in Opinion.

Screenshot: The New York Times

In the Opinion section, you have the ability to advocate for change. What do you hope readers will take away from this article, the project and the information you’re putting out?

Thompson: I hope they’re afraid. Like, I’m afraid (laughs). Maybe change some of their behavior, but that’s not gonna do very much for the world. I think some of this stuff is a slow build, you know? Congress is pretty distracted right now with some other important matters. I don’t think this story is triggering a new law next week, but what I hope is that it pushes the conversation forward on privacy, how important it is, how far companies have gone in a system where privacy is unshackled, and they can do what they want.

You can argue for banning all this stuff, but for people who are like, “I don’t really care. I have nothing to hide”… I think you can have nothing to hide and also have some limits on what these companies can do: how long they can keep it for, how granular it can be — in some circumstances they can get you down to a few feet of your location — and how often they can do it.

My ultimate hope is that people be concerned. Like Cambridge Analytica changes the view of Facebook, this can change the view of this area of how people look at their phone. I used to look at my phone like, “What a fun and convenient trick that I can get an alert when I walk near a pizza place.” That was so innocent a couple of years ago, and I hope that people change their minds after they read this, that is not an innocent thing anymore. It’s not a fun trick. It’s a business, and you’re the commodity.

Warzel: On my end, I hope that people for the first time, at the scale we are able to show it, understand what they are opting into. The onus is not on the consumer to fix this and police themselves. These companies need to be the ones that change. Lawmakers need to be the ones that put that pressure on them, but the service that I’m most happy to provide people is an understanding of what’s going on on their devices without their knowledge. I think in general, it’s so helpful to know what you’re up against.

I look at everything from Cambridge Analytica onward — and I think the Privacy Project is a part of this — as a greater reckoning with our devices and our privacy and the safety of our information. I think that’s a slow building process and one of the biggest tools in that fight is knowing what it is you’re up against. That’s why I’m so glad to see the way Stuart and his team were able to present this, because I think it gives people that understanding to know what they’re participating in.

This article first appeared in Storybench and is reproduced here with permission.

Erin Merkel studies journalism at Northeastern University. Storybench was founded in 2014 at Northeastern University’s Media Innovation graduate program in the School of Journalism as a “cookbook for digital storytelling.”