The pandemic is forcing TV journalists and filmmakers to adapt to new working conditions. Photo: cottonbro/Pexels

Breaking news stories about the coronavirus pandemic are currently dominating the media landscape. But powerful human stories and investigative angles are emerging that could make compelling long-form and documentary TV and video.

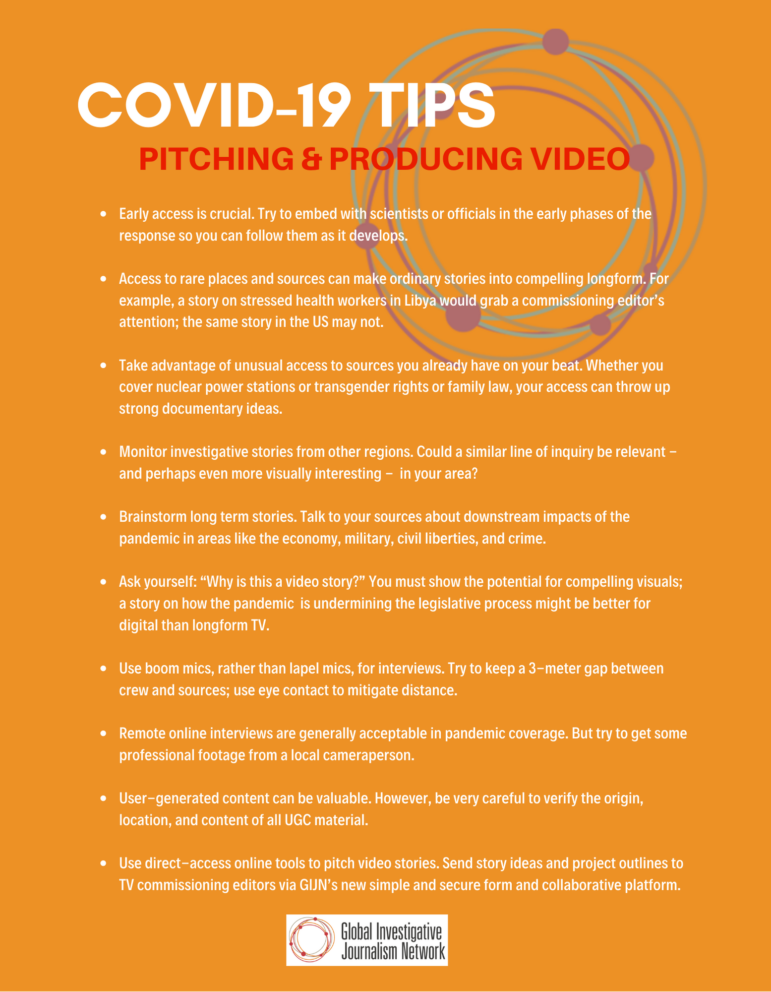

The pandemic is forcing filmmakers to adapt to new working conditions: using boom mics instead of lapel mics, acting as remote producers, and identifying new collaborators. Yet despite the obstacles presented by travel restrictions, health risks, and the ubiquity of daily news coverage, investigative filmmaking is continuing apace — and there are plenty of opportunities for journalists to pitch stories to major broadcasters.

GIJN has launched a simple and secure online tool for journalists to pitch global commissioning editors and find collaborators on TV and video long-form projects. Journalists with story ideas or projects under development can use the form to confidentially share an outline of their project with Swiss Public Television, Premières Lignes in France, the BBC (Global Current Affairs, BBC Arabic, and BBC Africa), PBS Frontline in the United States, and Canada’s CBC (French and English language investigations).

The new collaborative tool was launched during the third in GIJN’s webinar series Investigating The Pandemic. Nine senior video and TV commissioning editors from around the world shared what they’re looking for in long-form video pitches on the pandemic, and offered tips for journalists on how to pursue them in the face of unprecedented challenges. Some 160 investigative journalists and filmmakers from 48 countries joined the discussion.

What Editors Are Looking For

The editors cautioned journalists pitching ideas for TV documentaries that their angles need to be fresh, original, and narrative — and not just extended versions of the familiar stories we see in the daily news.

There are social-distancing workarounds for interviews – with Skype or Zoom interviews permissible for many broadcasters – and workarounds for travel, with the BBC, for instance, using producers in London to direct and edit content from the Middle East. But there are no workarounds for narratives that aren’t impactful or compelling, or suited to the visual medium.

“It’s about added value; [not] the stories we’re all thinking about,” said Jean-Philippe Ceppi, executive producer of the investigative program Temps Présent on Swiss public broadcaster RTS. There’s often a correlation between a film’s value and how hard it was to get the facts and visuals in it, he said. “We are expecting state-of-the-art television. How is the situation with COVID for a country at war?”

Importance of Collaboration

Ceppi said the traditional collaborative marketplace for long-form ideas “crumbled” in March, and that new collaborations and forums are urgently required to tackle both near and long-term projects. “We should reconnect, together, around investigative ideas, with forums like this,” he said.

Luc Hermann, executive director of France’s independent Premieres Lignes production company, said collaborations on the behavior of multinational companies during the pandemic – and particularly big pharma – would prove essential in the months and years ahead.

“We, alone in our countries, will never be able to be as strong as we can all be [together] in producing very ambitious documentaries,” he said.

Think Long Term

Edouard Perrin, investigative reporter at Premieres Lignes, said journalists’ radars should be tuned for visually compelling angles on the long-term fall-out – like the potential for blanket surveillance of citizens – as they pursue short term projects.

“How are our societies going to be threatened by a new era of surveillance, in terms of where we go and how we behave?” asked Perrin. “I’m also interested in the Chinese aspects of the story… the role of censorship over there, soft power, propaganda.”

“We’re always open to new ideas and pitches, and stories at all stages of development,” said Sarah Childress, senior editor at PBS Frontline, the flagship investigative series for public TV in the US. “The kind of stories we’re looking for are something fresh; something revelatory; particularly in what’s happening in the US, but also global stories.”

Childress said much of her team’s focus was on the “long tail” of the pandemic, and experimenting with new ways of telling stories. “For the next year or so, in some way, every story is going to be a COVID story – the effect on the economy, privacy, politics,” she said. “Since our films take anywhere from six to nine months to produce, we have to be thinking ahead, and stepping back.”

While the BBC has a lot of journalists producing stories around the world, there’s still plenty of room for freelance contributions, observed Mary Wilkinson, head of editorial content for BBC Global News.

“There’s a high bar to jump,” she said. “What we’re looking for is something we’ve not got access to, so that’s the domain of whistleblowers, bad actors, people profiting, insider testimony, or extremely good access films, where somebody has very quickly got off the mark and managed to embed themselves with somebody right at the heart of the story.”

“We’re also doing lots of long term thinking…on where severe impacts will be felt several months from now,” she said.

The investigative editor for BBC Africa, Marc Perkins, edits Africa Eye, which produces 20 investigative films per year, broadcast by 13 local partners and BBC World News. Largely tailored for African audiences, the connections between Africa and the world during the coronavirus pandemic have become a growing focal point for its network of freelance filmmakers.

Discussing key longer term issues for programs like Africa Eye, Perkins asked one of the most difficult questions emerging from the pandemic: “How will Africa survive after months of lock-downs?”

New Storytelling Approaches

Christopher Mitchell, documentaries editor at BBC Arabic, said the pandemic was opening up regional broadcasters to stories beyond their usual focus. “Ordinarily we cover the Middle East, but in the case of coronavirus, we will take, right now, anything that meets our editorial standards,” Mitchell said. “We’re much more open-minded about the geographical areas we cover. There is a thirst to really show what people are going through.”

“Longer term, we’d be interested in deeper investigations of coronavirus, specifically around the Arab world but not only that. We’re also interested in how the crisis is being used as a smokescreen for other activities.” BBC Arabic produces 30 or 60-minute films but are open to shorter videos as well.

Meanwhile, Adam Grimley, editor of the BBC’s Our World, said user-generated content had proved to be one successful model for telling the story of the pandemic, and he was keen to find other storytelling approaches. Our World runs 23-minute films, a mix of investigative, observational, and reporter-led stories.

Producing and directing films remotely is proving essential to pandemic coverage, given the travel restrictions, he said. “We’re having to be more nimble how we work: physically, how we edit the programs, how we work with reporters in the field, and also how we work with producers and reporters in the field,” Grimley said. “I’m totally open to ideas.”

Send your project ideas and outlines via GIJN’s new collaborative platform to support long-form television investigations into COVID-19.

GIJN’s next free webinar, Staying Safe: How to Report a Pandemic, in our Investigating the Pandemic series, will be held on April 23, 2020, 9:00 AM EDT.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.