Image: Canva

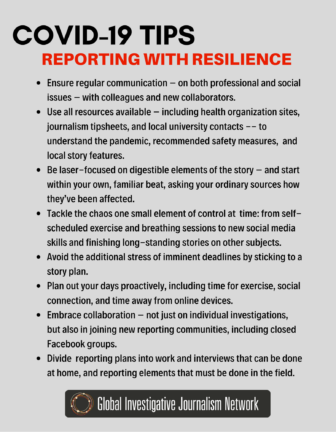

At first glance, the COVID-19 story appears overwhelming at every professional and personal level for individual reporters, from psychological trauma and shelved investigations, to the health risks to their families.

But experts say planning and daily habits can make the work manageable — and that the work itself, and the sense of making a difference, represents a coping strength that reporters can exploit.

In the second of GIJN’s free webinar series on Investigating the Pandemic last week, Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University, and Maria Teresa Ronderos, director and co-founder of the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística, spoke with 166 investigative reporters and editors from 53 countries on strategies for staying healthy and sane while covering the crisis.

The clear recommendation themes that emerged were: learn, plan, rest, and communicate.

The Tribe

Reporters covering any disaster in the field face the same basic responsibilities: doing no further harm to those affected, while also taking care of their own physical and mental health. However, with the coronavirus, reporters – like their audiences and sources – are personally immersed in the challenges and anxieties associated with the pandemic. And they face the additional imperative of trying to avoid bringing harm home to their families.

While Shapiro said reporters “as a tribe” have been shown by research to be well suited to handling trauma they encounter in stories, the protracted, immersive nature of the pandemic posed challenges and stress that could only be managed with planning.

“It’s going to be a period of some months of unrelenting, combined stresses and anxieties; of not knowing how this story ends; of wondering how people we love will [cope],” said Shapiro. “There are household stresses that are unique in this physical distancing era, of working from home, and of isolation. The brain needs recovery time, and we need to get proactive about planning for that: planning our days, so we’re building in self-care time; building in time so we get exercise or yoga or anything that lowers our biological arousal.”

Shapiro said reporters need to distinguish between factors they can and cannot control, and to lean on colleagues and familiar sources.

“We need to gain some control over small elements of this overwhelming global crisis by doing our work, and by planning — and that is one thing investigative journalists are best at,” he said.

Finding Focus

Ronderos said her three strategies for building resilience involved increased focus, collaboration, and continuity — to show both audiences and your own mind that the world is bigger than the virus, and will continue.

“You need to know what you can do and what you cannot do, and just let it go,” says Ronderos. “Talk a lot with your colleagues and editors. Most of our instinct is to win; to have a scoop… but, at this point, we need to collaborate more. And finish those non-virus stories and have them ready, and whenever you have a space, publish that story that’s not just [about the] pandemic. Hold governments to account in other areas; it gives people a sense that the world will continue.”

“You need to know what you can do and what you cannot do, and just let it go,” says Ronderos. “Talk a lot with your colleagues and editors. Most of our instinct is to win; to have a scoop… but, at this point, we need to collaborate more. And finish those non-virus stories and have them ready, and whenever you have a space, publish that story that’s not just [about the] pandemic. Hold governments to account in other areas; it gives people a sense that the world will continue.”

Despite the frontline exposure to trauma, the work itself represents a psychological bulwark against despair.

“A lot of people – even my family and friends — they feel they are impotent; that they cannot do anything about this crisis,” said Ronderos. “We get to do things about it as journalists. That feels so much better.”

Shapiro added: “Having a sense of work and mission is protective; an ethical code is protective — all of those characteristics are coping sources in the face of threats. There is a lot of good evidence that people who do well in the face of protracted stress are people with a strong sense of moral purpose.”

Of course, reporters also carried a special burden, he said, in that “we immerse ourselves in images and documents that carry a heavy trauma load.”

“We’ve talked a lot internationally about flattening the curve on [infections], but we as journalists need to think about flattening the stress curve – we don’t want that peak and crash,” he said. “We want to find activities that moderate that curve, by maintaining boundaries, having a self-care plan.

“All the research done on journalists in all kinds of crises says the single factor most associated with issues like PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] is social isolation. And the single most important resilience factor is peer support and other kinds of social connection. [Investigative reporters] tend to burrow into projects and exclude the world. We need to very deliberately plan those collegial connections, whether through webinars like this, smaller conversations with colleagues… or closed Facebook groups.”

Family Matters

The first attendee question focused on the challenge of not only avoiding bringing the virus home, but winning the confidence of family members that reporting the story in the field can be both responsible and worthwhile.

In addition to following the recommended physical protective measures to the letter — including the use of masks, gloves, and hand-washing — Ronderos said reporters need to actively share those guidelines with their family members, and be transparent about their reporting process.

“[Make sure] your families know you’re following the guidelines of very knowledgeable people — the World Health Organization, the Committee to Protect Journalists — and that you’re using all these resources to be protected,” she said.

Shapiro said it’s also important to minimize risk by choosing those field reporting excursions that are necessary to the story, and letting your family know that you’re doing so.

“Let’s be honest here: social interaction and on-scene in-person reporting does have some risks associated, to personal safety, and then the ethical challenge that we don’t want to be part of the spreading, or [perceived] that way. It’s important to assess when you can report in a more distanced way, and that you do field reporting that you’ve really thought about. You might also ask medical professions in your community how they and their families are handling it.”

For instance, Shapiro said one health worker told him that he changes out of his work clothes at the hospital, and seals them in a plastic bag for immediate washing on his return.

Meanwhile, responding to a question on obstruction from a Cambodia-based journalist – who had been chased away from reporting at a bank – Ronderos said journalists can report on the obstruction, and perhaps seek out sources who might be similarly frustrated.

Ronderos said reporters largely trapped at home by factors like quarantine or single-parent homeschooling could learn and practice open source reporting: “You could use this time to learn more about open source investigative journalism. Bellingcat are really good at this.”

In an earlier interview, Dr. Cait McMahon, director of Dart Asia Pacific, told GIJN that reporters face risks of psychological harm in three phases of their work: as witnesses to traumatic events; in interacting with victims; and in channeling those experiences in storytelling.

McMahon suggested that reporters conduct interviews that are likely to be emotionally taxing in the mornings, when energy levels are higher, and that they should pause for a break and avoid rushing to transcribe those interviews, if possible. And — where social distance is appropriate in face-to-face interviews – she said greater eye contact could help compensate for the greater physical distance.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.