Data journalists are starting to dig into the impact of the coronavirus and social distancing measures on poorer communities. Our NodeXL #ddj mapping from March 30 to April 5 finds The New York Times and Reuters using smartphone location tracking data to analyze the relationship between income and changes in people’s movements post-lockdowns, National Geographic visualizing how earlier implementation and longer social distancing measures can help slow infections and lower death rates, ProPublica looking into disproportionate infection rates among African Americans, and statistician Nathan Yau offering an R tutorial for a “flattening the curve” chart.

The Wealthy Stay Home while the Poor Commute

The implementation of social distancing measures across the US has offered a glimpse into its divides in socioeconomic status. Wealthier people are more likely to have desk jobs and can afford to stay home, while lower-income workers are usually employed in essential services that require them to get out and show up for work. The New York Times’ analysis of smartphone location data from Cuebiq revealed that those living in the highest-income locations were able to not only restrict their movement more than those in poorer areas, but they also had a head start. Journalist Jennifer Valentino-DeVries explains this story in a tweet thread. The Times also utilized Cuebiq data in its story, Where America Didn’t Stay Home Even as the Virus Spread.

As with all health and economic crises, the people hit hardest are always the most economically vulnerable. COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate, but our system does. It is built to prioritize the lives of the rich over everyone else. https://t.co/W0u1i9Z9Rt

— jeremy scahill (@jeremyscahill) April 4, 2020

Travel Habits by Income

As US social distancing measures started to kick in during the second week of March, people started traveling less. By month’s end, most of the country was staying close to home. Using data by the Kochava Collective, Reuters was able to compare the distances people (and their phones) traveled in March compared to February, which revealed some troubling trends. Statistician Nathan Yau wrote about this story in his blog.

Social distancing vs income (in the US). Basically, the bubbles creeping up to the top-left means that lower income people had to actually travel more after the lockdown: https://t.co/NRrcIeGZ9A pic.twitter.com/qX77NdoPX4

— Navin Kabra (@ngkabra) April 3, 2020

Lessons from the Spanish Flu

Social distancing isn’t a new idea — it was utilized during the 1918 flu pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, and helped saved thousands of lives. National Geographic visualized the death rates and the duration of social distancing measures in 36 American cities during that time. The charts showed that cities which ordered social distancing measures sooner and for longer periods usually slowed infections and lowered overall death rates.

In 1918, St. Louis was one of the most successful cities to flatten the curve of the flu pandemic. By implementing strong measures of social distancing, they were able to keep the number of flu cases and death rate low. The same principle applies now. https://t.co/OapF1K7DSH

— Nicole Galloway, CPA (@nicolergalloway) April 2, 2020

Simulating a Pandemic

You’ve probably seen The Washington Post’s viral simulation of a disease outbreak by now. Curious about the process behind the successful explainer? Datajournalism.com spoke to graphics reporter Harry Stevens to find out the motivations behind the piece, and the tools he used to produce the popular story.

What's the story behind the #Coronavirus simulator, the most-viewed article ever on the @WashingtonPost online? We interviewed @Harry_Stevens, creator of the visualisation: Where did he retrieve the #data from? How did it make an impact? https://t.co/cDJb5HaaIa #datajournalism pic.twitter.com/SVq86e7zvM

— DataJournalism.com (@datajournalism) March 31, 2020

R Tutorial for Flattening the Curve

“Flatten the curve” has become a common phrase when referring to the need to slow the spread of COVID-19 in order decrease strain on the healthcare system. Statistician Nathan Yau offers an R tutorial to create charts to illustrate the effects of decreasing social interaction.

#RStats nerds: run simulations for how to Flatten the Curve with this helpful download from Nathan Yauhttps://t.co/s3Cu00ofhN pic.twitter.com/c3c3upHhcX

— jagevans (@jagevans) March 18, 2020

Race Factor in Coronavirus Fatalities

ProPublica looked into early data on coronavirus cases and deaths in Milwaukee, Michigan and New Orleans, and found that African Americans were getting infected and dying of the coronavirus at higher — and disproportionate — rates.

“COVID is just unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation. This is the time to name racism as the cause of all of those things.“ https://t.co/XMPv5pVnnw

— Eugene Scott (@Eugene_Scott) April 3, 2020

Spain: Slowing the Chain of Infections

Since March 14, many Spaniards have confined themselves to their homes in a bid to reduce their number of daily contacts. The objective is to decrease the reproductive number of the COVID-19 virus — that is, the average number of people that each infected person can infect. El Pais explains this through “scrollytelling.” The piece is in Spanish, but easily understood using Google Translate.

Sánchez prorroga el estado de alarma hasta el 26 de abril.

Seguir la cuarentena es duro, pero necesario.

Ayuda leer artículos así, donde explican cómo el confinamiento frena los contagios.https://t.co/jjHxB14mtW

— María Navarro Sorolla (@mariapuntoes) April 4, 2020

Sourcing Johns Hopkins’ COVID-19 Data

The coronavirus cases dashboard run by the Johns Hopkins University, based in the United States, quickly became the go-to site for worldwide COVID-19 figures when the pandemic broke out. Puzzled by the data differences between the university and the Robert Koch Institute (Germany’s federal institution responsible for disease control and prevention), Tagesschau, ZAPP, and NDR dug into the sources used by Johns Hopkins and others. Benedict Witzenberger, data journalist at Süddeutsche Zeitung, wrote a blog post that references this. (In German.)

Wochenlang meldete die @tagesschau

Corona Zahlen der Johns Hopkins Universität – doch wo kommen die Daten her? U.a. von einer deutschen Zeitung. Tolle Recherche von @marvinmilatz https://t.co/YG0Oq8faoU— Claus Hesseling (@the_claus) April 3, 2020

Tracking Coronavirus in Turkey

VOYD, a Turkish association working on data literacy, is tracking and visualizing the number of coronavirus cases, deaths, and recoveries in Turkey and around world using data from Turkey’s Ministry of Health and Johns Hopkins University.

Türkiye ve dünya genelinde #koronavirüs hasta, vefat ve iyileşme sayılarını #veribülteni sayfamızdan takip edebilirsiniz. Veriler günlük olarak güncellenmektedir: https://t.co/l2kJmGC8cZ#Covid19 #ddj pic.twitter.com/KMk3WHkqOE

— VOYD (@voydorg) April 6, 2020

Information Design Journal

Alberto Cairo, Knight Chair in Visual Journalism at the University of Miami, highlights in his blog a free special issue of the Information Design Journal, which is a collection of submissions from the 2018 Information+ conference.

New post: Special issue of the Information Design Journal https://t.co/Ezakcg9W51 #dataViz #dataVisualization #infographics #dataJournalism #ddj pic.twitter.com/iCVKayWE3y

— Alberto Cairo (@AlbertoCairo) April 3, 2020

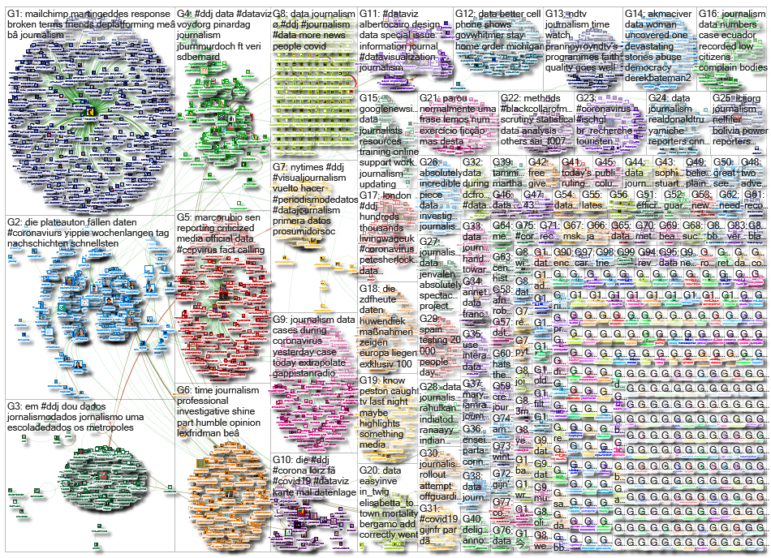

Thanks again to Marc Smith of Connected Action for gathering the links and graphing them. The Top Ten #ddj list is curated weekly.

Eunice Au is GIJN’s program coordinator. Previously, she was a Malaysia correspondent for Singapore’s The Straits Times, and a journalist at the New Straits Times. She has also written for The Sun, Malaysian Today, and Madam Chair.

Eunice Au is GIJN’s program coordinator. Previously, she was a Malaysia correspondent for Singapore’s The Straits Times, and a journalist at the New Straits Times. She has also written for The Sun, Malaysian Today, and Madam Chair.