Investigating the coronavirus pandemic is almost like covering a war, and may be one of the biggest stories we will cover in our lives.

Yet despite the unprecedented challenges with data and travel — and risks to reporters and their families — the frustration and isolation of officials also presents an opportunity for source-driven investigations and proxy data.

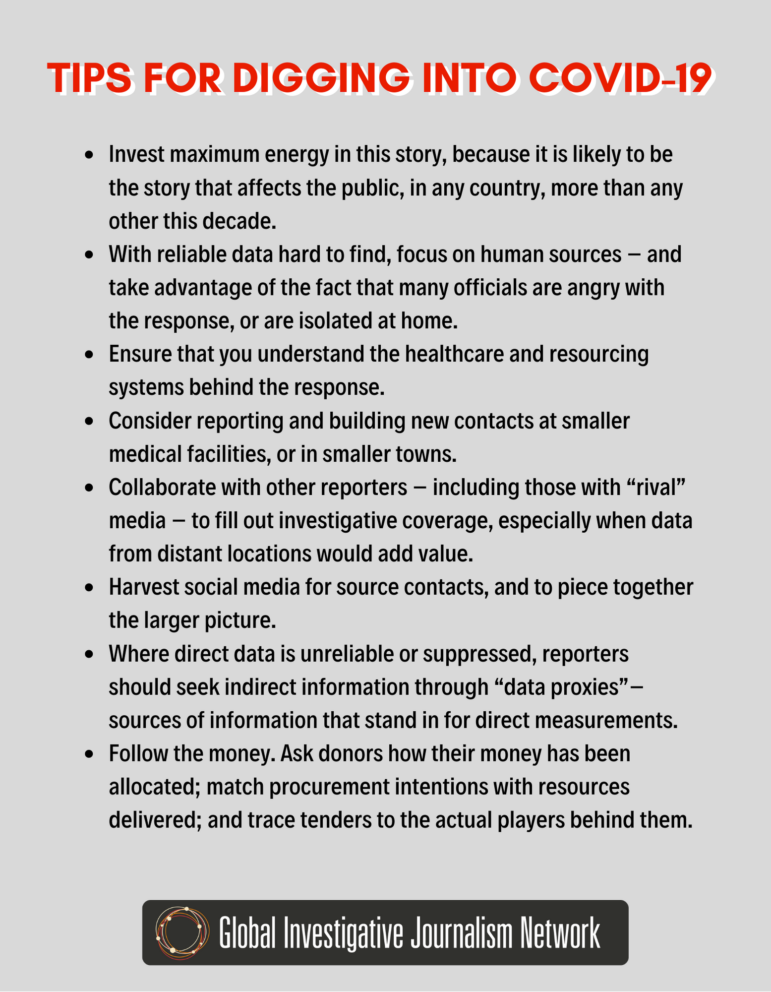

These were some of the insights of three veteran journalists on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis in the first of GIJN’s free webinar series, Investigating the Pandemic.

Last week’s panel on “Digging into COVID-19” included Gloria Riva, an investigative journalist at Italy’s L’Espresso; Joey Qi, GIJN’s Chinese editor; and Drew Sullivan, co-founder and editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

A total of 454 reporters, editors and others from 86 countries joined the webinar. They discussed dozens of angles ripe for inquiry, from government disinformation and the undermining of free speech to organized crime and the readiness of institutions.

Learning the System

For both the panelists and many of the journalists who joined the webinar, investigating the pandemic starts with understanding health systems – including healthcare procurement, skills availability, supply chains, as well as the mechanisms of the disease itself.

For both the panelists and many of the journalists who joined the webinar, investigating the pandemic starts with understanding health systems – including healthcare procurement, skills availability, supply chains, as well as the mechanisms of the disease itself.

“As investigative reporters, our first job is to figure out the system,” Sullivan said. “It was clear from the early reporting on this virus that reporters didn’t know how the disease worked. Therefore, they were manipulated. You have to learn, and to develop good sources.”

In one encouraging signal for reporters everywhere, Qi reported that – despite the health risks and data challenges – the pandemic had triggered a revival in the quality and volume of investigative stories in China, where COVID-19 first emerged.

Qi said individual reporters rapidly armed themselves with public health knowledge and used creative channels to access sources, while taking advantage of temporarily loosened censorship in China in an earlier stage of the crisis.

Story of the Decade

Meanwhile, there are widespread signs that organized crime is already exploiting both public fear and public money. Riva said the Italian mafia is actively trying to enter the response supply chain, while Sullivan warned that “there’s a lot of cheating and corrupt stuff going on across the board.”

Warning that the scope of the story might only be fully understood in two years or more, Sullivan issued a virtual call-to-arms for reporters: “This is the story of the decade. For investigative reporters it’s difficult, because it seems like a daily story. But what’s emerging is that it is a huge investigative journalism story.

“Covering COVID-19 a lot like being a war reporter. There are very few [direct] sources; there is an enemy; a period of chaos… and it’s also dangerous, you could get killed if you’re not careful. And it’s difficult to get to the front lines. But credit to my colleagues for some exceptional work being done.”

Dealing with Data Deficits

One common challenge for reporters is the lack of reliable information and useful context on healthcare resources as well as infections and deaths.

The panel offered several work-arounds, including benchmarking and comparison. Riva noted that benchmarking a country’s available intensive care beds against those in a country like Germany offered readers helpful context, as would comparing the ideal or normal ratio of doctors and nurses to patients. “The perfect number is five patients for each nurse, and eight for each doctor,” she said. “[In Italy] we have 15 patients for each nurse – and they are more important than the doctors [in this pandemic].”

Riva said many health organizations are barring staff from speaking with reporters. However, she said the “good news” is that nurses and doctors want to speak – particularly about their personal trauma and the lack of equipment. She noted that health worker unions are emerging as particularly useful sources.

Meanwhile, Sullivan noted that where virus-specific data is missing in documents, reporters could compare current monthly hospital expenditures and procurements with a pre-pandemic month, and note the difference for readers.

Qi added that social media mining is emerging as a major tool for investigative reporters on the pandemic. “People are posting messages on Sina Weibo [China’s Twitter-like platform] asking for help, and you can send direct messages to them,” he said. “You can cooperate with different media and with journalists on the front line.”

The heightened need to collaborate with “rival” media was echoed by the panel, with travel restrictions imposed on reporters and the virus now circulating in over 100 countries.

Source-Driven Investigations

In a problem voiced by several reporters attending the webinar, journalists in developing countries with autocratic governments face information blackouts or outright disinformation on resources and infection rates.

A reporter in Liberia noted that the information crackdown in the west African country is so severe that “many citizens still do not think the virus is in the country.” Another attendee wrote that the government had banned journalists from visiting isolation centers and hospitals in Nigeria, while a journalist in Egypt added that “we think the government is hiding a lot of information.”

Panelists suggested that reporters in these circumstances use social media to identify and develop sources at hospitals and government agencies.

Sullivan said that — in addition to consulting international databases — reporters dealing with scarce official information could try to identify “data proxies” — sources of information that stand in for direct measurements. For instance, reporters might gain an approximation of death rates through calls to casket makers, or checking publicly available death certificates.

And since many developing countries receive financial aid from outside sources, he suggested reporters could contact donors to ask how their money had been spent, and search for reports and audits on the funding.

Planning for Investigations

One priority that emerged is the need to plan the timing of investigations according to the likely availability of data.

So price-gouging investigations, for instance, could be pursued immediately, because prices for masks and sanitizers, for example, are advertised and available online. Sullivan warned that reporters should beware of assuming that slightly higher prices involve unethical gouging, since companies might have to absorb the cost of new product lines and distribution channels.

Meanwhile, investigating exploitation by organized crime may need more time. Riva said her team will look at mafia connections to the response over the coming months, as data patterns emerge that help distinguish between front companies and legitimate ones.

Months into the future, Sullivan suggested that using the pandemic as cover for political abuses of election laws could also be explored.

For the near term, the clear strategy for information gathering must be focused more on humans than documents.

“Data is very tricky, when a lot of conclusions rely on an epidemiological study and not a journalism data analysis,” Sullivan explained. “This is far more complex, and we need to respect the science. We won’t always get access to the important documents until much later.

“But when people are dying, people get angry, and when people get angry, they talk. And when they are not in their office, but at home, that’s a great time to talk to people. As journalists, we need to be much more source-driven during this time, to talk to people who have knowledge.”

Follow the Money

Questions from attendees focused on issues of data access, media suppression in China, disinformation, and how reporters can track procurement.

Sullivan warned against stories that track the spread of the infection to individuals. “Stay away from traps about how the disease spread, or who ‘caused’ the outbreak in a particular area,” he said. “That often leads to racist reporting, or blaming people for getting sick.

“The most important issue is how governments are handling this. We haven’t seen how badly some of these countries have handled it yet because the disease hasn’t run its course, but we will start to see a lot of people dying in the next two months, and those governments are not going to tolerate that version of history being out there, so there will be a lot of internal propaganda to spin this.”

Qi said he had seen more high quality investigative stories from Chinese news media during a recent 15-day window than he had seen in more than a year – due to the diligence and courage of individual reporters, and a temporary softening in state censorship.

He said promising investigative ideas had emerged from inquiries in smaller medical facilities and towns, where patients often make their first contact with the health system. “Journalists often focus on major cities and major hospitals, but you may find important leads in small clinics and towns,” he said. “People with fever are more likely to visit small health centers, you can find very good leads.”

Another theme from the discussion was the need to be systematic and focused, given the sheer volume of money moving around, and the number of people who aren’t. Sullivan said one avenue for inquiry was whether government departments were buying useless equipment simply for the appearance of quick response.

“We must follow the money in this story, as always,” Sullivan noted. “Governments are buying large amounts of medical supplies, but not always getting large amounts of medical supplies.

“Where is the assistance going? Where the assistance is from donors, maybe we can find this out from donors. A lot money is being re-budgeted. We need to look at budgets; which departments are getting the money. You might find much of it is going to propaganda and law enforcement, and not health.”

The next webinar in the series “Investigating the Pandemic” will be on Wednesday April 8 at 9 am EDT covering Resilience and Reporting: Staying Healthy and Sane.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.

Rowan Philp is an award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.