What tools do investigative journalists use in the course of their work? In this series, we ask journalists from around the world to share some of their favorites with GIJN’s readers.

Joel Konopo.

This week we spoke with Joel Konopo, co-founder and managing partner of the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit newsroom in Gaborone, Botswana. INK is a member of the Global Investigative Journalism Network. Konopo told us how he has used social media and satellite imagery, among other tools, to inspire new investigations or take existing projects to the next level.

Konopo was previously editor of the Botswana Guardian, one of the country’s leading national newspapers. He was also part of a team of journalists that covered the Panama Papers as they related to Botswana. In one of the biggest stories he worked on at INK, he reported that funds and equipment meant for the military had been diverted for the construction of a vast compound belonging to then-president Ian Khama.

Most recently, he was awarded a John S. Knight fellowship, allowing him to spend an academic year studying journalistic innovation at Stanford University in the United States. Now back in Botswana, Konopo is eager to put to use what he has learned about data and tech-assisted reporting, as well as to encourage his colleagues and peers to adopt these approaches.

Here are some of Konopo’s current favorite tools:

Satellite Imagery

Satellite image of the president’s compound. Photo: Courtesy INK

“In 2017, two of my colleagues and I traveled to a rural part of Botswana to investigate a tip-off that the president was having a major private compound built for himself. We were arrested by masked men before we even got close to the location, were detained for a few hours, then were driven miles away before being finally released.

“After that, we wondered how to complete our investigation. We considered using a drone or a helicopter to get closer to the compound, but then discarded those options as we thought they might also be detected. Satellite imagery turned out to be the best option, but Google Earth was not sufficiently up to date: We spotted some features on the ground that did not appear on its images. We ended up contracting DigitalGlobe to obtain the shots we needed.

“We provided them with the GPS coordinates of the alleged compound, and they sent back up-to-date images, confirming the allegation. That allowed us to publish the story, which made a lot of noise both for what it revealed and for the innovative method we had used. The story drew global attention and I now teach other journalists how to use technology to expose wrongdoing in repressive environments.

“The use of DigitalGlobe’s service cost us $5,000, which restricts our reliance on such tools. In this case it was the best way to stand the story up. There are ways in which satellite imagery could help us in other investigations, too, but the cost certainly is a factor.”

Drones

“Although drones were not the right solution for the presidential compound story, they can work for other projects.

“We recently purchased a DJI Mavic Pro to present audiences with striking bird’s-eye videos to illustrate our investigations. We haven’t used it yet because you need to obtain a license from the Civil Aviation Authority of Botswana to fly drones. We have applied for a license and I expect we’ll get it soon. Once we do we’ll be able to use it whenever we want, although restrictions will still apply: You can fly the drone at a range of no more than 500 meters and a height of no more than 40 meters, and never above a large crowd without official permission, which limits what you can do with it.

A DJI Mavic Pro drone. Photo: Flickr / Juan Carlos Morales S.

“Drone journalism remains uncommon in Africa, and authorities are skeptical about journalists using drones to tell stories. But drones can really help bring a story to life. For example, if you are doing a story on communities affected by a nearby open pit mine, drone footage can present the problem very clearly, by showing the whole area from above and the deplorable conditions endured. That is the sort of journalism we want to do with it.

“Beyond drones, we are beginning to use other visual tools, too. We recently purchased the Mevo Plus camera to livestream footage on Facebook and Twitter. Mevo is useful as it gives you a television-like experience on social media. We also use GoPro Hero7 for extreme photography, such as when we cover extreme sports or investigate poaching.

“These tools can assist our reporting on the ground, but they also serve the purpose of making our investigations more visually appealing, so that they reach a broader audience online. At the end of the day, what’s the point of investigations if they don’t have an audience?”

Wickr

“Everyone at INK has an end-to-end encrypted Protonmail account dedicated specifically to sensitive communication, and I also sometimes email via Tutanota, another safe service.

Image: Courtesy Wickr

“More recently I have started using Wickr for phone messaging. I like it because it’s similar to WhatsApp and Signal, but even more secure — you can sign up without inputting either your name or phone number, and messages expire automatically, leaving no trace. All you have to do is share the pseudonym you are using with the person you want to talk to. It’s one of the tools I learned about while at Stanford, and I am now using it to report on Botswana’s lifting of the ban on elephant hunting. The government is very sensitive on this issue, so we really have to operate under the radar. I asked a source to download Wickr, which they did; that source trusted me all the more for it, because it showed that I was making a special effort to protect them.

“I still use other messaging services, but Wickr is best for complete safety. It is important for us journalists to prevent the government from intercepting our communications when we report on such issues.”

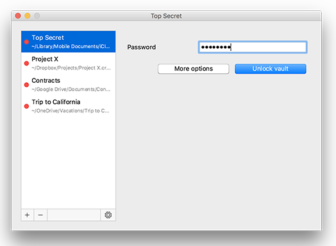

Cryptomator

Image: Courtesy Cryptomator

“I used to store all of my data on my hard drive, even the most sensitive documents. Now I keep valuable confidential information on Cryptomator, the encrypted cloud service. It has been a big improvement. I asked a computer expert to search for sensitive information on my laptop; he couldn’t locate it. I use an incognito web browser to access Cryptomator, which is itself encrypted and requires three-step authentication, so there’s no trace of the files on my laptop. I have recently added a VPN to further hide my data and browsing location. I want to make sure that those who might be interested in knowing who I am communicating with find it difficult to track my messages and online searches.”

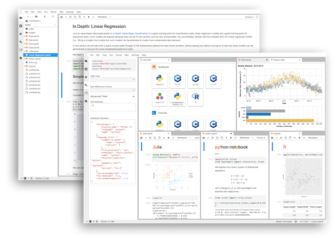

Jupyter

Image: Courtesy Jupyter

“There will be a general election in October this year in Botswana, so we are collecting data about the different candidates and their campaigns to establish patterns concerning for example their age, gender, and the source of their campaign donations.

“I have found Jupyter to be an excellent way to organize these data sets and generate clear graphs for analysis. The service seamlessly charts data in a way that is very helpful for complex research. Sorting out election data manually would take forever; doing it through Jupyter is much faster. Even the laziest person can do it in a short amount of time. It’s an excellent way for journalists who have limited knowledge of sophisticated software to engage in data journalism.”

Social Media

“I find Facebook to be a place first of misinformation, but it can also generate useful tip-offs. In Botswana, WhatsApp in particular is a place where information, even sensitive, is shared very liberally and quickly. So you can actually get very useful information on there, then start digging into those stories.

“When the country’s head of intelligence, Isaac Kgosi, was dismissed in April last year by the new president, information that the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crimes had compiled about him was leaked. All of a sudden it was all over social media, including confidential information about Kgosi’s bank accounts. As an investigative journalist I started looking into the allegations, which were that Kgosi had diverted millions of dollars to purchase weapons in Israel. It all began with the WhatsApp leak, which the Directorate later confirmed was accurate.

“People sometimes share information on WhatsApp groups without realizing how important it is. It’s a good starting point for me, even though it can sometimes take a long time to verify. It can also be a source of misinformation, so you have to be careful. It’s important for me to stay abreast of what is being said on social media, then to sift through it all.”

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. He has written investigative reports on finance in the Middle East and Africa for Euromoney Magazine, and contributed obituaries to The Independent.

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. He has written investigative reports on finance in the Middle East and Africa for Euromoney Magazine, and contributed obituaries to The Independent.