INK co-founders Ntibinyane Ntibinyane and Joel Konopo (back row) with admin officer Motlatsi Mabalani and program manager Samantha Pilane (front row). Photo: Courtesy INK Centre for Investigative Journalism

Editor’s Note: The Global Investigative Journalism Network has 185 member organizations in 77 countries. Many work on the front lines of independent media and innovative journalism. In this series, we look at the extraordinary work they’re doing and the formidable challenges they face, from financial survival to attacks on press freedom. This week we profile Botswana’s INK Centre for Investigative Journalism.

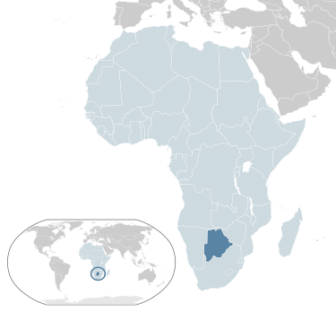

Landlocked Botswana in Southern Africa. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Two investigative editors took huge pay cuts to launch Botswana’s first nonprofit newsroom. A year later, they took another, temporary cut just to pay for a single satellite image which proved that the country’s president had abused state funds to build a private lodge.

The INK Centre for Investigative Journalism and its staff of eight have existed on a precarious, shoestring budget for four years, while facing legal and even physical threats from state organs, and giving away their scoops for free.

Yet the nonprofit, based in Botswana’s capital Gaborone, is not in survival mode. Instead, it is in hyper-ambitious innovation mode, having recently purchased an aerial drone, launched a fact-checking initiative, pursued ambitious stories, and won seed funding to produce video stories in seTswana on a new mobile platform. (While English is the country’s official language, seTswana is the most widely spoken indigenous language in the country.)

Recognizing that some 5 million people around Southern Africa speak seTswana — and that mobile data is increasingly affordable for even rural communities — the new INK24 platform aims to produce both investigative and human interest stories in multimedia, smartphone formats, and in the dominant language of Botswana and communities near its borders.

Joel Konopo, managing partner at INK, says the video and mobile-first platform could help solve the problem of impact in the region by delivering stories in a simpler and more understandable form.

“Our story on the president’s residence got a few ‘wow’ comments on social media. When you expose that level of corruption, you expect mass outrage, but we are just not getting the level of public reaction that leads to pressure on government,” say Konopo. “We need to reach grassroots communities with stories they can easily digest.”

A satellite image showing the lodge built using state funds. Photo: Courtesy INK Centre for Investigative Journalism

Botswana is the size of Texas, but has less than one-tenth its population, at 2.25 million. While its economy is widely considered a model for the region – with per capita GDP rising above $8,200 per year – press freedom has lagged amid other development indicators, and its news media have suffered arrests of reporters and state censorship. This year, Botswana was ranked 44th on the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index, behind African countries like Namibia and Burkina Faso.

The former editor of the Botswana Guardian newspaper, Konopo has taken on public officials at every level of power, including the former president of Botswana’s Court of Appeal. Co-founder and senior reporter Ntibinyane Ntibinyane began his career as a reporter at the Botswana Guardian, and later became head of investigations for the Midweek Sun and its sister publications. (He is a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists; read ICIJ’s interview with Ntibinyane here).

Konopo says he and Ntibinyane both “took big salary cuts” to launch INK in 2015, and that they had done so to avoid commercial and political interference in editorial independence.

In just a few years, INK has published a string of big investigations. In 2016, it showed that funds and equipment meant for the Botswana Defense Force had been diverted for the construction of a vast compound at Mosu, owned by then-president Ian Khama. In its first year – 2015 – it revealed extrajudicial killings of suspected Namibian poachers. Its reporters have also contributed to the Pulitzer prize-winning Panama Papers collaboration. INK has published stories on its own website, as well as sharing stories with publishers throughout Botswana and South Africa.

However, INK recently ran a survey of both urban and rural communities which revealed that thousands of Botswanans were not engaging with traditional investigative reporting, and that many preferred streamed video stories in their home language. Konopo says that they now plan to reach new communities by breaking stories down using bullet points and short video clips, and translating all investigations into the local language.

He says the INK24 platform has received seed funding from the Open Society Foundations, and that a small team of videographers and multimedia reporters will be assembled to report in parallel with the INK investigations team.

“Prices of mobile phones have dropped, and data bundles aren’t that expensive anymore — with the help of the government, it must be said, who have helped to liberalize telecoms,” Konopo says. “You can now access mobile data for $6 per month, and the service providers have enabled greater access to social media. We are also seeking equipment that does Facebook Live for events of interest: Almost no one is doing this in media in Southern Africa.”

He says INK plans to soon pursue its first video-for-mobile story – choosing a “simple elephant-poaching” exposé for the pilot. This choice of issue illustrates a contrarian story angling approach that has set INK apart from other news media in the region since its inception. While many publishers show little sympathy for wildlife poachers, INK took the risk of championing the basic human rights of alleged Namibian poachers in its “shoot-to-kill” series.

Ntibinyane says: “Elephants are killing some people in the rural areas as a result of policies that [put them in proximity], and no one talks about that. Everyone [in the media] talks about the welfare and population of elephants, and about tourism — but what about the father who leaves behind a wife and children as a result of these contacts? People out there tell us that this is a real concern for them, and so we feel that we must respond.”

Last year, the team exposed the plight of another group widely ignored in the media — 500 refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo — and revealed the appalling conditions they were living in.

Dr. Letshwiti Tutwane, a journalism lecturer at the University of Botswana and a former Fulbright scholar, describes INK as a “good work in progress.”

“INK is still relatively new, but it is slowly making its way into the media landscape in Botswana,” says Tutwane. “A few of their stories such as the Panama Papers and investigations into fraudulent academic qualifications were quite shaking, and have had the attention of the public. So was the story on the illegal use of state resources to finance part of the construction of the private residence and landing strip for the former president.”

While he believes that stories produced in seTswana will definitely boost impact, Tutwane says he is not sure how INK will pull off a successful mobile platform in Botswana.

“Seeing is believing,” he says. “They will face several challenges. [But] in the age of fake news, visual evidence is necessary to achieve credibility. There is a lot of corruption in Botswana which needs to be uprooted.”

As an investigative reporter for Botswana’s independent Mmegi daily newspaper, Innocent Selatlhwa has watched INK’s development closely since 2015.

“INK has taken investigative journalism to a new level in the country, and they continue to set the pace,” says Selatlhwa, adding that he was one of several newspaper reporters who benefited from training programs thanks to initiatives and invitations from INK and its nonprofit partners. “INK has developed a lot of reporters to be [more] investigative and not just give you the ‘he said, she said’ stories,” he says.

INK’s team currently comprises two full-time investigative reporters — in addition to Ntibinyane’s reporting contributions — and four admin and support staff. Ntibinyane says INK has also received a commitment to fund a dedicated fact-checker for a year.

The potential of the mobile platform forms just one element in a complex set of options for INK’s future sustainability. For Ntibinyane, the first problem is that INK is not only expected to provide publishers with its stories for free, but that it sometimes has to actually pay to provide free content.

“We did a 32-page pull-out on the plight of refugees and gave it to the Botswana Gazette – and we actually had to pay for the printing for that insert!” he chuckles. “Publishers don’t even help us negotiate the print prices. Meanwhile, donor support is declining. The current situation is not sustainable, and so we are exploring several options not only to continue, but to grow.”

One option is INK’s potential participation in a new Shared Services Centre (SSC): a centralized fundraising hub for investigative journalism nonprofits that is currently being set up by South Africa’s nonprofit investigative center, amaBhungane. The purpose of the SSC is to reduce the fundraising administrative burden on small nonprofits, and to make it easier and cheaper for donors to assess grants.

Konopo says targeted paywall revenue is unlikely for the INK business model. Instead, INK plans to explore new, modest revenue streams from publishing partners, crowdfunding, possible media platform revenue, and larger foundation grants for deeper and broader impact.

“We are ambitious,” he says. “First of all, we are trying to position ourselves as a Southern African investigative journalism unit, and we already have an audience far beyond the borders of Botswana. And we know that you are considered less of a risk for donors, the larger that you are.”

While Ntibinyane sees mobile-first platforms as ideal for data journalism, the source of that data will pose a major challenge, as Botswana has no freedom of information law.

“The previous president made it easy for public servants, in particular, to distrust journalists. That is changing,” he says. “But we still don’t have laws that allow access to information [or to] protect whistleblowers — and we still have to deal with a hostile government.”

He adds that their everyday challenges lie in changes to regulations: “For example, regulations have been changed so that if you want to see a deed of ownership, now you need consent from the property owner to see the deed at the registry.”

Last year, Konopo completed a John S. Knight fellowship at Stanford University studying journalistic innovation.

“And I took advantage of my presence in Silicon Valley to buy this cool gadget — this [aerial] drone,” he recalls. “We are going to apply for a license to operate it. We will use every tool.”

Rowan Philp is a multiple award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.

Rowan Philp is a multiple award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.