Satellite imagery of a Uighur detention camp in Xinjiang, China. Photo: Courtesy Geospatial World

Satellite imagery has become an indispensable tool in investigative journalism for fact-finding, gauging the impact of a particular situation and figuring out the exact details. It has also become an effective tool in conflict zones and for correctly and precisely pinpointing human rights violations or assessing developmental patterns.

Investigative journalism often weaves reportage, narratives of people on the ground and storytelling.

In conflict zones and other volatile regions that are constantly rated as the “most hazardous places for journalists,” satellite imagery can emerge as a reliable alternative.

Be it the satellite imagery that shows the extent of electrification in North Korea or satellite imagery that shows houses of Rohingyas bulldozed by the Myanmar army, a lot of path-breaking stories have been broken with the help of satellite imagery.

Before-and-after imagery shows Rohingya villages bulldozed.

In 1995, satellite images provided evidence of mass executions in Srebrenica, in the former Yugoslavia.

Images of Srebrenica in the former Yugoslavia. Courtesy: NSA archives

In the year 2007, satellite imagery was used to expose the construction of an airstrip in Botswana, at the private home of then-president Ian Khama.

Construction of an airstrip in central Botswana.

In a historic moment in Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, the president since the country’s independence and former hero of the liberation struggle turned authoritarian strongman, was ousted after 37 years at the helm by a 2017 coup.

This image, taken by DigitalGlobe‘s WorldView-2 satellite, shows Mugabe’s palatial home in Harare, nicknamed “Blue Roof,” where he was briefly kept under house arrest.

“Blue Roof,” Harare, Zimbabwe.

Iran has long tried to clandestinely obtain nuclear weapons. The contentious Iranian nuclear deal under US President Barack Obama aimed to curb Iran’s nuclear program. Satellite imagery by Planet shocked the world when it exposed secret Iranian facilities that were developing nuclear rockets.

Planet imagery shows Iran nuclear site.

Satellite imagery has also shown the detention camps or the euphemistically called “re-education camps” where thousands of Uighur Muslims from the Xinjiang province of China are held.

Satellite imagery of Xinjiang, China.

DigitalGlobe satellite imagery also showed the massive influx of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, highlighting the acute humanitarian crisis.

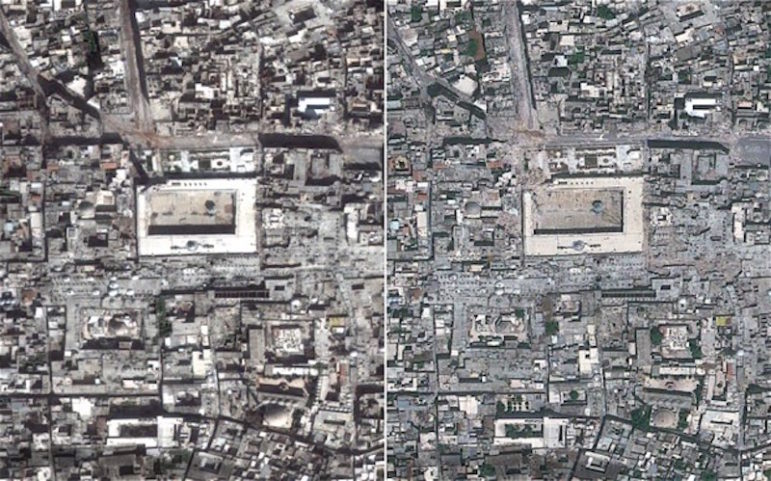

In the protracted conflict in Syria, satellite imagery identified strongholds of the terrorist group ISIS; the extent of devastation in Syria’s former industrial and financial hub Aleppo; the havoc wreaked in the third-largest city Homs; and the archaeological and heritage sites that have been ravaged in the ongoing conflict.

Before-and-after satellite imagery showing the destruction of Aleppo, Syria.

In Afghanistan – which is at the strategic crossroads of Central Asia and has witnessed intermittent conflict for more than three decades – Copernicus satellite imagery monitored internal displacement and helped the UN to know the extent of the man-made catastrophe.

In the newly-carved and conflict-prone South Sudan, satellite imagery showed the miserable conditions in refugee camps, and DigitalGlobe satellite imagery was instrumental in tracking food scarcity and eventually assisting in relief. In the conflict in Darfur, satellite imagery highlighted the destruction of villages and the egregious violation of human rights.

DigitalGlobe satellite imagery of the Darfur region in Sudan.

In 2014, DigitalGlobe released five satellite images that showed Russian troops and heavy artillery crossing the Ukrainian border. The images were picked up by NATO and they contradicted the Kremlin’s claim that there had been no Russian-backed infiltration in Eastern Ukraine.

In 2017, North Korea sent shock waves throughout the globe by declaring major successes in its intercontinental ballistic missile program and nuclear program.

Factory in Pyongsong, North Korea.

The above image was taken by DigitalGlobe’s WorldView-2 satellite on November 21. It shows the factory in Pyongsong where the Hwasong-15 ICBM is believed to have been developed.

Other than conflict zones and wars, satellite imagery also helps journalists investigating natural disasters or studying deprivation patterns.

These are just a few prominent examples highlighting the importance of satellite imagery in unearthing information, separating hard facts from the miasma of speculations, deliberate obfuscations and hearsay.

Bygone is the era when investigative journalists had to rely on reams of data and sources and then do the painstaking task of not only winnowing the wheat from the chaff by themselves but also ensuring the information was reliable.

Satellite imagery is opening up new frontiers in journalism and vindicating the old motto of empowering people through knowledge.

This article first appeared in Geospatial World and is reproduced here with permission.

Aditya Chaturvedi is Assistant Editor of Geospatial World. Chaturvedi is an electronics engineer by qualification. His curiosity is piqued by modern history, contemporary socio-political events, literature, geopolitics and travelogues.

Aditya Chaturvedi is Assistant Editor of Geospatial World. Chaturvedi is an electronics engineer by qualification. His curiosity is piqued by modern history, contemporary socio-political events, literature, geopolitics and travelogues.