Shahin Gheiybe is a convicted criminal hiding in Iran. Photo: Instagram

A fugitive convict from the Netherlands had been taunting Dutch police with provocative pictures and videos from Iran, playing a game of “catch me if you can” on Instagram. “I love my freedom. And the weather,” he has stated.

Bellingcat was able to reveal the last known location of the criminal with the help of over 60 Twitter users. Here’s how we did that.

The Escape

The fugitive, 35-year-old Shahin Gheiybe, is on the Dutch “Most Wanted” list. On July 5, 2011, Gheiybe was sentenced for two attempted murders. In the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, on July 6, 2009, he tried to kill two individuals by shooting at them. He also robbed them of 175,000 euros. Gheiybe, born in Iran, was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 13 years.

He managed to escape from prison on October 6, 2011, and has been on the run ever since. The police in the Netherlands have searched for this individual since then.

The convict posts on Instagram (there are over 170 photos and videos) about his whereabouts (here is the original link to his private account, and a backup link), mostly in Iran. He has almost never tagged himself with a specific geolocation, just towns and places. Only once, for a street in Teheran, the coordinates were very precise. Gheiybe’s Instagram account was created in July 2015. It became private in March, after he landed on the list of most wanted criminals.

His last Instagram post is a clip from Scarface (archived post). Gheiybe’s Instagram account contains provocative material, like personal videos accusing the ruling judge in the Netherlands, claiming “the truth is very different.” He tries to explain to his followers that he is a nice guy who made a mistake.

A Dutch police spokesperson called this “shocking” and added, “It is unbelievable how he distorts the facts and that he cares so little about his victims and our society. Apparently he considers himself untouchable in Iran.”

Problems to Solve

A problem with scrutinizing any of the Instagram posts is that the convict can deceive the police by using bogus location tags in Instagram, backdating the information or otherwise hiding his real whereabouts. We looked mostly at clues where the convict is clearly visible and, at the same time, is near a traceable object (Gheiybe near a car, in a club, holding a branded knife).

Using that method, we tried to reduce the risk of being deceived ourselves.

Another problem centered on the ethics of impacting the investigation. If we can find a last known location — as we ultimately did — any convict undoubtedly becomes aware that they are being zeroed in on.

Without crowdsourcing, any fugitive’s last address will be much harder to find. Bellingcat got the help of over 60 people who researched with us via Twitter. That research was conducted mostly on March 18, 2019.

The police told the public they didn’t know the location. But the public (via crowdsourcing) ultimately did.

This is an example of how transparency works both ways: It can be used by both good and bad people. We decided that we would send the police even the tiniest leads during our investigation. And that we would alert them the moment we would find something actionable, so they had at least a head start.

Technical Preparations

To get our hands on all the Instagram posts, we needed to prepare first. We followed these three steps:

Browse Instagram On Desktop

We didn’t want to fiddle with a mobile or tablet, but work on a desktop computer. To do that, we downloaded Desktop for Instagram, a Chrome plug-in.

Download Videos

Downloading over 170 Instagram videos and photos manually is time consuming. We used a plug-in for Chrome called Downloader for Instagram. It’s fast, downloads all material in full resolution, and also supports Instagram stories downloads.

Find Hidden Connections

To find the hidden connection between Instagram users, to find what our target liked, and much more, we used Helper Tools for Instagram, again a plug-in for Chrome.

In the picture above, for example, the convict is next to a liquor display — focusing in on specific objects can sometimes lead to finding connections. Or, at the very least, you find something about the target’s likes and lifestyle.

Question 1: Whom Did He Meet?

Dutch police asked the Dutch public for help with this case on TV.

For English followers: translation of "Opsporing Verzocht" (17/17) so you understand my last tweets a little better. Full explainer coming up tonight. pic.twitter.com/3aplJ1Yz6F

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 19, 2019

One question was: Who did the convict interact with? Maybe his interlocutors know his possible bogus identity, like a false passport or a false name. We concentrated on that question first.

A Man And A Statue:

This picture, uploaded on Nov. 27, 2018, shows our target play-fighting a statue, which perfectly suits our need to have an identifiable object and our target in the same photo. We did reverse image search in Google and Yandex — and, as it is often the case, Yandex was the better choice.

This is how we found Kish Island, some 200 kilometers away from Dubai.

A slightly bizarre promotional story about this island tells you what you can do there:

“Women sit with cigarette in hand, wearing colorful headscarves pushed right back to reveal plenty of make-up and expensive hair-dos,” and “the wide, palm tree-lined boulevards that circle the island of 100 square kilometers are full of top-end cars, including luxury American models.”

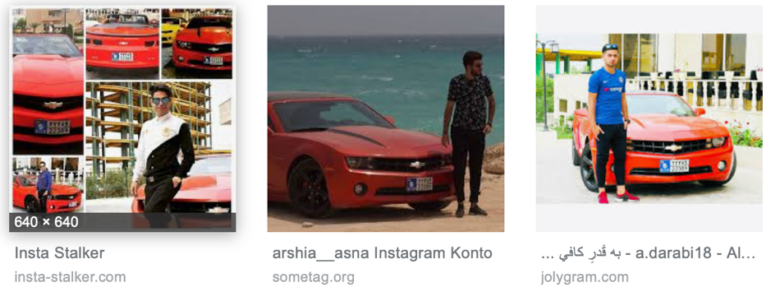

On the same day, Nov. 27, 2018, we found a video where our target was near a car with a recognizable license plate. The video shows our target getting into a red car and driving away in it.

The next step was for people with a great amount of patience. We tried to find hotels in Kish via Google Streetview that matched the building in the video background. In the end, we found the exact spot (pictured here in daylight):

Reverse imaging the license plate didn’t work at first. Sometimes, Google simply doesn’t recognize a blown-up detail of a photo.

You can, however, approach this problem by just typing in words you can see into Google Images, without reverse searching the photo itself:

This leads to images of tourists driving the same red Chevrolet Camaro with the same license plate.

Eventually, we found the Camaro supplier by clicking on some Instagram posts featuring happy clients.

Our convict didn’t steal the car. After he drove the Camaro, people were still renting it, as we found out after checking another series of posts by satisfied renters. So, we assume he had rented the vehicle as well.

Kish Rent Car, a local car rental place, can shine a light on the current identity of our target. We have a first possible answer to our initial question: Whom did our target meet?

Finding Replies Sent to Other Instagram Accounts

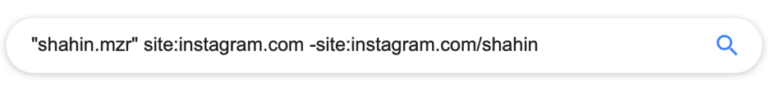

Did our target reply to other Instagrammers? To find out, we used this formula in Google.

We don’t want to see postings from the target’s own account (hence we exclude site:instagram.com/shahin) but are still interested if he (hence shahin.mzr) posted comments on the Instagram posts of others (hence site:instagram.com). This is what we found:

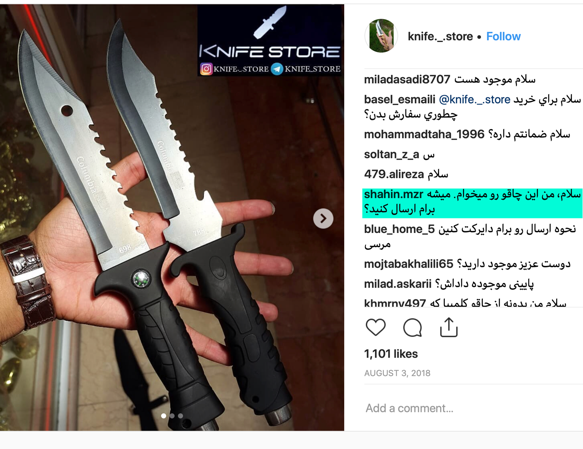

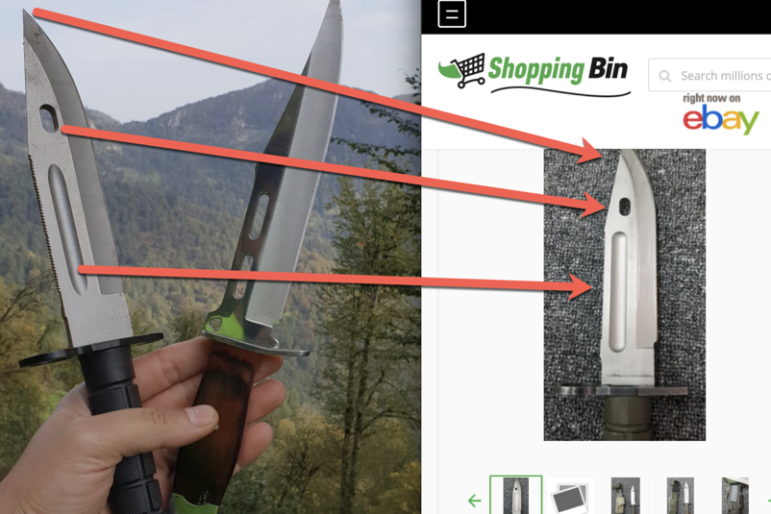

Around Aug. 3, 2018, our target asks knife._.store, the Instagram account of an Iranian knife seller, if he can buy a knife and if it can be sent to him. He was prepared to pay 65,000 toman, which is around around $15, for the knife.

Later that year, on Oct. 22, 2018, Gheyibe posted a photo of two knives on his own Instagram account. The one to the left (see photo above) is the Phrobis III Buck Gen 4 Fighting Knife M9 Scabbard USGI Military Wire Cutter. This model had gone on sale for a short moment in the autumn of 2018, at the previously mentioned knife store in Iran.

We were able to find the Farsi Telegram account and exact address of the dealer, another answer to the question as to whom our target was contacting.

A summary of our findings up until finding the specific knife reference on the target’s account was given to the police and later published in a Dutch newspaper, which had asked Bellingcat for assistance. I also presented the preliminary findings at a conference of the VVOJ.

#LROJ19: scoop van Bellingcat https://t.co/IQkmPrieUE

— Bellingcat (@bellingcat) March 19, 2019

Question 2: Where Is He Now?

Because things were going smoothly, we tackled the hardest question: Where is the target now? We concentrated on a video from March 9, 2019.

Here is the original footage. And no – I am not sure. Why does it look like further north? pic.twitter.com/syEgIRW87K

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

In this video, Gheiybe mocks the police while standing in front of a house.

More Technical Preparations

We dissected the 35 seconds of video from March 9, 2019, and exported it into over 1200 separate images, each covering a different part of the area, resulting in just one photo of all of the frames the video. For that, we used a sophisticated program called Agisoft Metashape, and this method (the description is currently only available in German). You see our target more than once because he was moving in the frame.

The reason behind doing this conversion is that we get a better view of all the details of the video, a method that was also used in “Inside the Trenches of an Information War.”

Problems to Solve

Our target posted the video on March 9, 2019, but he may have filmed it months ago.

We needed to find something in the video that helped with chronolocation, i.e., finding out exactly when it was shot.

Besides the when, we needed more proof of the where: There is no hint of a location and no geotag in the Instagram post itself.

Staring at the Magnolias

We stared long and hard at the white flowers, but only thanks to botanical experts was our next lead found.

The plant is called the Magnolia stellata. It bears large, showy white or pink flowers, most of them in early spring, before its leaves open. These flowers don’t last long. The magnolia from the video probably blossomed at the end of February or in early March, very near to the publication date of the video. It was probably shot in the northern part of Iran, because Magnolia stellata wouldn’t be comfortable with the climate in the south of the country. We believed it to be a wealthy neighborhood, because of the well-maintained garden and the size of the house.

The Garbage Can

The garbage bin in front of the house is of a color and model that is sold in Iran.

We were able to sharpen the Iranian (?) bin. Now compare this bin to some bins we are sure that they are from Iran. Can they be the same? What do you think? (7/7) pic.twitter.com/NlOo9iEOUR

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

A Reflection Offers More Clues

If you look closely at the house in the background, you see a window:

And there is a reflection in the window as shown here. There is another house in that reflection.

We had to focus on a wealthy area in the north of Iran with at least three houses in the middle of what looks like the woods.

The Architectural Style

And our public @bellingcat quest continues! Look at the architecture of the building in video compared with something @Tohn_Jitor found in this area https://t.co/IUcE9xo2x7 Can you help to find the building in first photo? (7/7) pic.twitter.com/aNog8jEq9Y

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

The details from the balcony are typical of some buildings in the Iranian province of Mazandaran, local people told us via Twitter.

Going Through Reference Material

We went back to the Instagram videos of Gheiybe looking for material that could be from Mazandaran. In one video, published on Oct. 5, 2018, he is driving through the rain.

In front of him is a car, and to the left of him you can see a sign of some sort of shop (1). The shop is a real estate firm in Abbasabad, Mazandaran. The license plate (2) is also local. It starts with the number 82, which is specific to the area, as Iranian journalist Ershad Alijani from France 24 Observers found out.

We have a new clue. In one of his videos, this still can be found. The real estate firm to the left is from Abbasabad . And the license plate is also from Abbasabad/ Tonekabon Can all #osint lovers research for a house near Abbasabad that matches the house on the right? (8/8) pic.twitter.com/eFiY61orSk

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

The architectural style we previously honed in on is present in Abbasabad. At this point, Twitter was going wild. Some Iranians started spontaneously hunting for magnolias and orange garbage cans in the area, by car.

The mystery, however, was solved in London. Nathan Lee, a reporter for ITV, recently followed a workshop from Bellingcat with Eliot Higgins and the author of this piece.

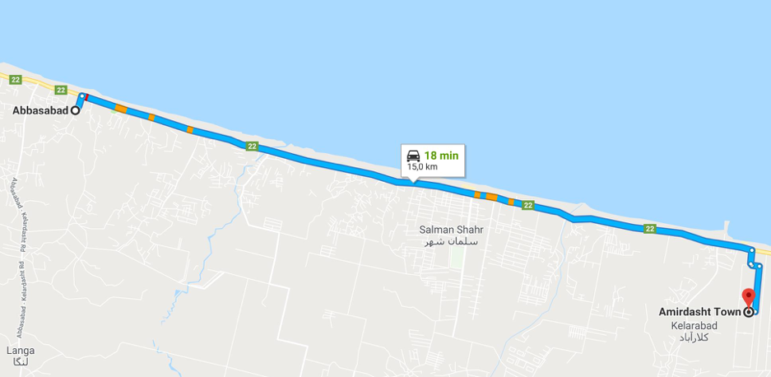

“The Bellingcat course helped a lot. I did various Google image searches of Abbasabad, Tonekabon, Amirdasht and went on the premise of it being a rich/well-to-do area of Iran,” he wrote. Just 15 kilometers from Abbasabad, in Amirdasht Town, Nathan spotted the house of the convicted fugitive.

Hi @henkvaness , @bellingcat @EliotHiggins – I think I've found it. Amirdasht in Iran. 36.691453, 51.258657

Matching pillars, lamp outside directly above doorway and to the side, shrubbery, plinths outside which can be seen at the end of the video. pic.twitter.com/Wf5mlGAyEC

— Nathan Lee (@NathanLeeTV) March 18, 2019

If you turn the 360 view around, to the house across the street, there is a clear view of the same orange bin we found earlier.

With the help of crowdsourcing, the second question was finally answered. I couldn’t find the right words, as evidenced by my typo:

I am tremendous proud of all the #OSINT people who helped @bellingcat this morning in finding a fugitive criminal person. The exact location is https://t.co/FVlIweW1wF and the police has been notified. Thanks all! Unsung heroes are @ErshadAlijani and @NathanLeeTV ! (10/10) pic.twitter.com/bxmqtKNHkT

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

We asked a local Iranian to find out more about the house. It is guarded.

The dessert; here is the entrance of the place were the criminal fugitive is hiding (12/12) pic.twitter.com/CfpZgS5W7W

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 18, 2019

The houses in the area are not vacation homes, and the neighborhood consists of people who own their own places.

Once more we went back to older Instagram postings. We wanted to find out if some of the videos were shot inside the house we saw in his Instagram feed. We found three videos that were probably made in that house because they matched the placement of windows and other details we saw on the exterior.

We found similar footage on another Instagram account. That account belongs to a friend of the fugitive. She is a lawyer. The fugitive attended this friend’s wedding, according both to his and her postings. The groom is Gheiybe’s best friend. The bride claims it’s her house. Therefore, our target most likely lived at a friend’s house.

@bellingcat @henkvaness Short movie placed on Shahin Gheiybe instagram this morning was filmed in a female's friend house (same as the wedding pictures). See attachment for proof. pic.twitter.com/BLMbmcV5eQ

— Erik Wassenaar (@ErikLambooy) March 21, 2019

Now that we knew what the inside of the house looked like, we could chronolocate this Instagram post, from Christmas 2018, in the same house. Therefore, our target has probably lived for months in that house.

The wanted fugitive has since confirmed that the location is right:

For what it's worth! Dutch most wanted fugitive just said about @bellingcat article "Yes, they found the exact location" in a chat with one of the editors. Check also https://t.co/qwtglUn1HE (17/17) pic.twitter.com/tCet2hEbiJ

— ʜᴇɴᴋ ᴠᴀɴ ᴇss (@henkvaness) March 21, 2019

Can you trust the statement of a wanted convict? We don’t need to answer that question ourselves. We found the exact spot thanks to open source investigation. But what now?

Epilogue

Gathering all of our findings, we went to the Dutch police. They were very happy with the information and used it in their daily briefing, when they decided what to do next. But their hands were tied.

The Dutch Public Prosecutor’s office announced that they would not be able to arrest our wanted convict: “We have no extradition treaty. We studied our options, but we don’t have any legal basis to arrest him or ask the Iranian government to do that.”

While this answer may be underwhelming, our quest demonstrates how social media and crowdsourcing can help pinpoint a criminal’s location. Even if said criminal thought he was playing a clever cat-and-mouse game.

This article first appeared in Bellingcat and is reproduced here with permission.

Dutch-born Henk van Ess teaches internet research, social media, and multimedia/cross media. The veteran trainer travels around Europe doing Internet research workshops. His projects include “Fact-Checking the Web,” Handbook Datajournalism, and speaking as a social media and web research specialist.

Dutch-born Henk van Ess teaches internet research, social media, and multimedia/cross media. The veteran trainer travels around Europe doing Internet research workshops. His projects include “Fact-Checking the Web,” Handbook Datajournalism, and speaking as a social media and web research specialist.