ProPublica Illinois’ narrative investigation about a problematic clinical drug trial featured a mother’s online journal, which records the disastrous side effects experienced by her 10-year-old boy. Image: Courtesy ProPublica Illinois

Effective reporters prize public records — documents produced, and often concealed, by government officials or others in power. Coupled with interviews and other research, such records buttress investigative reports with authority that can lay bare official misdeeds and bring about important reforms.

Few writers, however, take advantage of another documentary source that can be just as illuminating: private records that add unforgettable ingredients to stories.

“People record their lives in all sorts of ways,” Louise Kiernan, editor-in-chief of ProPublica Illinois, said in a 2003 story I wrote for Poynter Online extolling private records. “And often what they write or is written about them is more true than what they tell you.” When she was at the Chicago Tribune, Pulitzer Prize winner Kiernan had used journal excerpts to describe the postpartum depression of a woman who committed suicide; a colleague mined teacher evaluations to profile a dying professor. (You can find other examples in the story linked above; the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine retrieves expired links.)

This past October, a team of ProPublica Illinois journalists under Kiernan’s direction used an unusual private record as the primary material in “We Will Keep on Fighting for Him,” an investigative narrative that exposed the human impact of a clinical drug trial of children with bipolar disorder. Following an investigation by reporter Jodi S. Cohen of flawed clinical trials at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Cohen teamed with engagement reporter Logan Jaffe. Jaffe fashioned a call-out to from families who participated in the study, and obtained an online journal kept from late 2010 to early 2011 by a woman named Aline. The journal records the disastrous side effects experienced by Aline’s 10-year-old son, Wilson, while participating in one of the studies. (Aline and Wilson are middle names used in the ProPublica story as part of an agreement to protect the family’s privacy.)

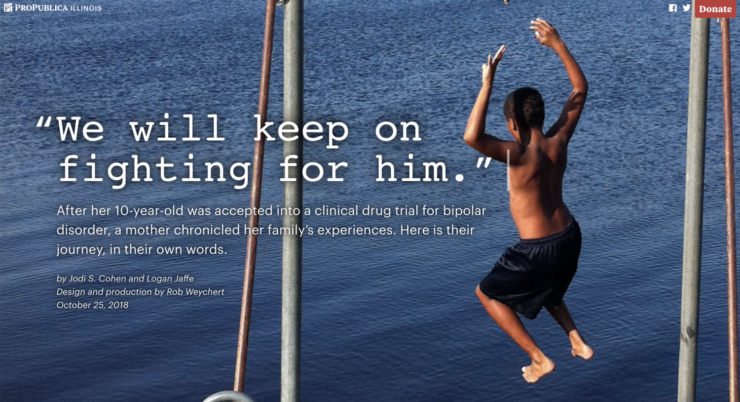

Wilson, the young boy who was part of a flawed clinical drug trial to treat children with mental health issues. Photos were chosen to illuminate Wilson’s personality while protecting his identity. (Family photo, used with permission.)

Then, in an unusual move, ProPublica turned nearly half of the published story over to the mother and son. Rather than hew to the tradition of having the journalists control the bulk of the material in a standard interview/quote fashion, this story cedes control to the sources’ personal narrative. Or, as Kiernan says, it “breaks the ‘rules’ in all the right ways.” Together the reporters crafted a digressive structure that shifts from Cohen and Jaffe’s contextual narrative — based on the traditional tools of documents, interviews and research — to the private record of a family’s torment, in what one colleague called “an emotional piece of evidence.” They also persuaded mother and son to reflect back on the devastating impact of Wilson’s treatment. These were used as real-time annotations linked to Aline’s eight-year-old reflections and paired in a scrolling interactive presentation produced by designer Rob Weychert.

The result is a story that is infuriating because of what it reveals about abuse of power and heartbreaking because of what it reveals about the individual costs. As a masterful piece of craft, it also demonstrates the power of private records. It serves as an object lesson for narrative writers who can use yearbooks, letters, diaries, photos and other personal ephemera to enhance storytelling with intimate and revealing details. Such stories don’t always require a FOIA or hours toiling in a courthouse basement; by simply asking sources to hunt in their attics and basements and memory boxes, writers can locate records that reveal a character’s inner life and history.

Nieman Storyboard reached out to the ProPublica Illinois team, which included deputy editor Steve Mills, for a behind-the-scenes look at the reporting, writing and collaboration that produced this remarkable story. Our email conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Normally, journalists write their own stories, based chiefly on interviews with sources. In this case, ProPublica Illinois let two sources — a mother and child — tell more than half of “We will keep on fighting for him.” What led to this approach?

LOGAN JAFFE: We should rewind a bit and talk about how we ended up hearing from Aline, the mother, in the first place. We had put out a call in Jodi Cohen’s earlier investigation, hoping to hear from participants in [University of Illinois psychiatrist Dr. Mani] Pavuluri’s studies. We did that because UIC was providing little information about how participants were affected, in part due to privacy rules. But we still wanted to tell that part of the story. (Read: What We Learned From Letting a Mother and Her Son Tell Their Own Story, from our newsletter.) One of Aline’s daughters, who works in a university research lab, read Jodi’s earlier story, and emailed it to her mom, who then emailed us to say her son had participated in Pavuluri’s studies and that she had kept a journal about the experience.

First, Jodi, Louise, Steve and me all read through her journal. It moved all of us. We realized it was much more than just about the study’s impact on one child; it was about a family struggling with mental illness, about the love, desperation and hope that led them to enroll in the study in the first place, and what led them to make the decision they ultimately did by the end.

I think we all felt the rawness, emotion and even typos of Aline’s journal writings were part of the story. And that story is her and her family’s story. Investigative journalism relies on documents to tell stories, and Aline’s journal is a document – already in narrative form. We wanted to preserve the document, in a way, because it’s the most true form of her story.

Describe the decision-making process that went into securing that personal material.

JODI S. COHEN: Aline emailed us a few days after we published our first investigation into the UIC research problems. She mentioned that she had kept a fairly detailed journal of her son’s experience. I remember thinking “What are the chances?” I recently heard another journalist speak about how she wrote a story based on a diary and played it cool and didn’t act too excited with the source when she heard about the journal. I can’t say I acted that way.

Aline and I spoke by phone the next day and at the end of the conversation I asked if she would be willing to share her journal. She said she would discuss it with her son first, and then she sent it to me the following week.

As soon as I finished reading it, I knew we had to find a way to share her journal with the public. It was too powerful not to. About a half-dozen reporters and editors read the journal and we jointly decided to use it. The next step was figuring out the best way to do so.

The journal was written eight years ago and, as our reporting revealed, much has happened since then with the doctor who oversaw the lithium studies and the university’s lax oversight. The family knows more now than they did then, and the developments in their family and with UIC’s research problems is part of the story. We came up with the idea of the annotations and the mom and son were on board with it. We met with them, each separately, several times to do the interviews that became the annotations.

Example of how ProPublica annotated an eight-year-old family journal to help fill in gaps and add current context.

One of the more challenging aspects of this design was getting the right photos, and enough of them, to make it work while still using only the family’s personal materials. We wanted it to feel like a family scrapbook. Also, we needed to make sure none of the photos revealed the family’s identity. We looked through their photos several times until we found the ones that would work.

Investigative stories rely on public records, as did your initial investigation into the clinical trial that devastated the life of Wilson and his family. How did you feel, in terms of the story’s credibility, about relying so heavily on a personal journal as a primary source?

COHEN: The family’s recollections, as told through the journal, are backed up by other records. There is a lot of reporting that the reader doesn’t necessarily see but that is interspersed in the parts written by Logan and me, and that provides the editorial context. We obtained documents about the UIC studies through the Freedom of Information Act, including consent forms. The family obtained some documents that the university wouldn’t provide to me because of privacy laws. Those records backed up the journal, and we used them like other pieces of evidence. For example, there were tests results that showed Wilson had lithium toxicity — which Aline mentions in the journal – and there were doctor notes describing the adverse reaction Wilson had from medication.

Once you had the journals, how much material did you have to deal with? How did you decide what to use and what to leave out, and which passages to annotate with their thoughts and feelings? How much editing took place and how involved were the mother and child in the process?

COHEN: The journal is probably twice as long as what we published. We wanted to keep readers’ attention and still stay true to the main messages in Aline’s journal. The time readers spent with the story was more than double the average time.

During the interviews, we asked questions tied directly to the [journal] entries. We used Trint, an online transcription service, to transcribe the interviews. For the annotations, we generally picked ones that either explained their current thinking on what happened in the past, or helped the reader understand what they were thinking at the time. All the material surrounding the journal — the annotations and the ProPublica Illinois text — is designed to help the reader through the journal and to provide the necessary context.

The mother and son did not have any input or decision-making in which annotations we used, just as sources in a story can’t choose which quotes are used.

JAFFE: We also sat with Aline and went through photos she had taken in 2010 and 2011. We worked with her to select photos from her home computer that would still maintain their family’s privacy but also provide a glimpse into their lives from that time. Then Louise [Kiernan] had the great idea of asking Aline to write one last journal entry that tied up her reflections and also how their family is today. Aline was so willing to participate and be part of the process — but, as Jodi mentioned, there were also clear editorial lines.

Logan, what does your job as engagement reporter entail?

JAFFE: My job is to find and create ways for our reporting to be informed by people at the center of it, and then deliver that story and information back to those people and communities in a way that makes sense to them. (Read: ProPublica Illinois is Listening).

What role did you play in this story?

JAFFE: My role at first was to help get Jodi’s first investigation in front of people who may have been most affected by it — participants of the study. It was also to encourage people to share our call-out for study participants to contact us.

Once we heard from Aline, my role shifted a bit, and I focused on how we could best involve Aline and Wilson in our actual reporting and help bring their story into the present. Jodi and I crafted specific questions to ask them based on the journal. I have a background in radio and multimedia, so I recorded their interviews and helped think through how we should be using all of our different assets to tell the story in a way that also maintained the family’s authenticity.

In the writing, a lot of my role was to preserve the transparency of our process about the call-out and how we ended up hearing from Aline. When the story came out, I kept track of where various conversations surrounding the story were happening, and invited Aline to get involved in the comments section of the story, which she did. I also managed our Reddit “Ask Me Anything” we hosted with Aline a week or so after publication.

Louise, you’ve used private records in narratives before. What is so valuable about them for writers of narrative nonfiction?

LOUISE KIERNAN: The ways that people document their lives for themselves and for their family and friends — whether it’s a journal or a postcard or even a text — can be incredibly powerful reporting tools. These records transport you to a moment that would be almost impossible to recapture or reconstruct with the same authenticity. The passage of time inevitably alters the narrative of any event and if you’re lucky enough to come across these kinds of materials, it’s like you’re opening a secret door to step back inside it.

Logan, there’s a great photo of you in front of a board covered with strips of paper. Could you explain what’s going on there?

JAFFE: Whew. We definitely made up our workflow as we went along. Our four major “assets” or building blocks to the story were 1) the journal entries 2) the annotations 3) the family photos and 4) whatever text we would write to help link the pieces together. We wanted all of these pieces to really speak with each other, and not be redundant. We also wanted to be able to try different combinations depending on which worked the best.

Reporter Logan Jaffe works the project’s visual storyboard, a color-coded outline of the various elements: the family’s journal entries, the reporters’ contextual passages and the annotations adding explanation and clarity. Photo: Courtesy ProPublica Illinois

First, we printed out the journal. Then, we printed out the possible annotations. We cut each journal entry out with scissors. Then we cut each annotation out, too, and mounted each on two different colors of paper to indicate whose annotations they were. We used large rolls of paper for each journal entry, and highlighted text within the journal entries that corresponded with the colors on which the annotations were mounted. Then we started taping annotations for those entries onto those sheets of paper. That’s how we also figured out where we should write between them, depending on what we knew from our reporting and what parts of the story needed to be linked between entries.

Essentially, what you’re seeing is a storyboard with lots of literal moving parts. It allowed us to be a bit more flexible and visualize the full presentation of the story in a way we couldn’t really “see” in a Google doc. It’s kind of like a manual Google doc, but instead of control-C and control-V we’re using actual scissors and paste (or tape). We used Sharpies to edit and trim text at first, then when Jodi and I felt we had a pretty solid first draft, we made a Google doc that replicated our “art project.”

What was the goal of the interactive presentation?

ROB WEYCHERT: The design’s goal is to orient the reader as the story moves back and forth in time and among multiple perspectives. There are eight-year-old journal entries written by Aline, full of uncertainty and emotion; recent reflections on those entries by Aline and Wilson, offering the benefit of hindsight; and supplemental text by ProPublica which provides additional context from a somewhat clinical distance. To manage those shifts in a reasonably subtle fashion requires careful attention to typography and layout.

Aline’s journal entries anchor the story and are set in a monospace font (the sort you’d see on a typewriter), which helps establish the journal text as personal, unpolished, and from an earlier time. When the journal is interrupted by annotations or supplemental text, a sans-serif font helps the reader manage the shift in time frame back to the present day, and the speakers are color-coded: Aline and Wilson, the subjects of the story, get saturated colors; ProPublica, a bystander, gets a muted gray. And when there’s enough space on the screen, the annotations get their own column to the right of the journal, making their role even more explicit.

Despite our best efforts, though, some readers might still find all this code-switching a bit overwhelming, which is why we included the option to hide annotations.

Example of the interactive design of ProPublica’s annotated narrative investigation. Courtesy: ProPublica Illinois

The narrative structure is digressive, juxtaposing a chronological third-person narrative with first-person journal entries and annotations by Aline and Wilson. How did you decide when to shift gears — from narrative to journal and vice versa — as you structured and wrote the story?

JAFFE: In the storyboarding, we got a sense of where some holes were that we could fill in with our reporting. Those decisions were made based on narrative gaps, but also on whether we had information to clarify or expand on anything Aline wrote about in the journals. We also used it to build character and context to clarify the stakes throughout the story.

COHEN: We wrote when we felt like the reader needed more to understand the narrative or the family. This includes background about the family members and about how the family discovered the severity of Wilson’s mental illness. We also wrote about the problems with UIC’s research and about the confusion over what studies Wilson participated in. We had obtained other documents that help explain what Aline wrote in the journal, so we included some of those, as well as the responses from the university and Pavuluri. Also, since we didn’t publish all the journal entries, there are some points where we summarize entries to catch readers up.

How and when were editors involved?

LOUISE KIERNAN: We are a small operation and we all work together in one room, so I think everyone is essentially involved in every story from the beginning. We had informal conversations with one another and as a group from the moment Jodi got the journal, as well as scheduled story meetings. Our editing process is very collaborative. Steve [Mills] did the primary hands-on editing and I jumped in as needed. I think I had a sense of what we wanted the story to communicate narratively and emotionally and tried whenever I could to help us get there — but it didn’t take much work on my part.

STEVE MILLS: I saw our goal as letting the family speak for itself as much as possible, in the journal and in the annotations. So I think we wanted to keep that interstitial material — the parts Jodi and Logan wrote — to a minimum, to just help guide the reader. I think that’s what has made it such an intimate experience for readers.

How did Aline and Wilson respond to their story?

COHEN: Aline told me at one point that her goal for the story was “to tell our family story in a way that would give hope to others.” She also wanted to be the person that she wished she had been while going through the most challenging times with her sons, both of whom have severe mental illness. The story ends with her saying: “I want this to be the story for other families that I was looking for eight years ago.”

In her effort to try to help others, she has directly responded to comments written in response to the story and she participated in a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” to answer questions. Every time I thank her for working with us to tell her story, she turns around and thanks us for getting her story to the public despite how difficult it was to relive that challenging period in their lives.

How long did it take to produce the story, start to finish?

KIERNAN: Jodi and Logan started putting the pieces together in the summer but we set the story aside for a couple of months while Jodi worked on a series of investigations into shelters for immigrant children in Chicago. Then we picked it back up in late September and the story ran in late October. The story required far more reporting than might be immediately apparent; it wasn’t simply a matter of republishing the journal. Jodi obtained and reviewed hundreds of pages of documents to confirm what had happened to Wilson. She and Logan conducted hours of interviews with Aline and Wilson for the annotations. They worked together to edit the journal entries and line them up with the annotated comments to tell a clear, compelling story. In addition to all that, we had to build the presentation from scratch.

The story gives the last word to Aline, Wilson’s mother, in a present-day reflection. Why end the story this way?

KIERNAN: The idea to do that just popped into my head during one of our story meetings. I remember saying, “Okay, I have this wacky idea…” I wasn’t sure what Jodi, Logan and Steve would think but we all immediately liked it. The journal had always felt as though it needed a conclusion and, most importantly, if our guiding principle was that Aline and Wilson should be able to tell their own story, it seemed only fitting that they should write the ending.

In its use of private records and ceding so much story landscape to sources, the story departs from usual norms. Were there any other out-of-the-ordinary decisions?

KIERNAN: Because this was such a personal story, we decided to let Aline and her family review it before publication. They didn’t ask to see the story in advance and we didn’t promise to change anything they might object to, but they had placed so much trust in us that we wanted to make sure they saw the story before it ran and that we could talk through any potential issues. Jodi drove out to their house, which is some distance from Chicago, with her laptop to show them the presentation. Aline didn’t ask us to change a word.

This article first appeared on Nieman Storyboard and is reproduced here with permission.

Chip Scanlan

Chip Scanlan