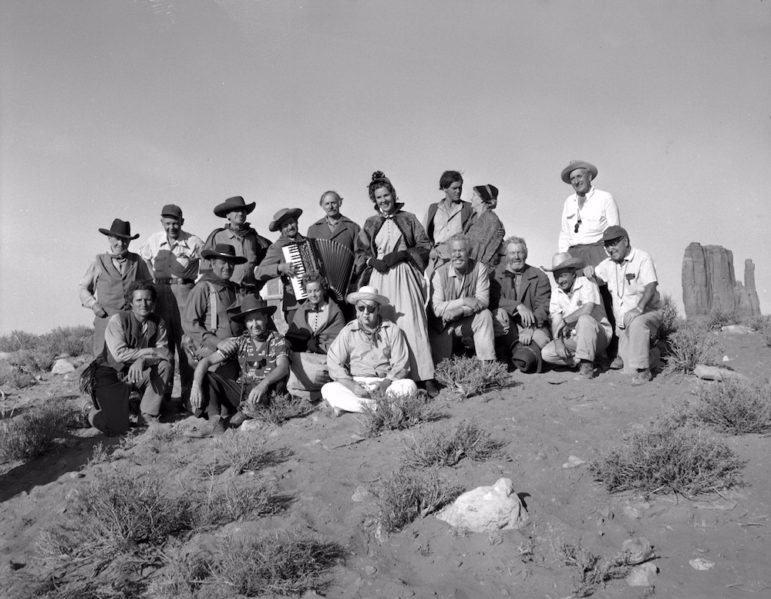

John Ford with the cast and crew of “The Searchers.” Photo: Allen Reed / Courtesy Gregory Reed

The first thing many people will tell you about researching and writing nonfiction books is that it’s nothing like writing news articles or feature stories. My own experience has been different.

For me, research is just a polite word for reporting, and what I do now in creating 125,000-word nonfiction books isn’t dramatically different from writing news stories and features at The Washington Post, where I worked for 27 years. The basics remain the same: Start by going to all the places where your story occurs, talk to anyone you can find who knows about the things you want to know about, track down any documents that exist and repeat the process again and again (and again) until you’re satisfied you’ve found, verified and understood everything you can.

My two most recent books have each taken an iconic Western movie and explored how it was made and the historical era it reflects. The first of these was about John Ford’s “The Searchers” (1956) starring John Wayne, based on a novel by Alan LeMay about the abduction of a 9-year-old Texas girl by Comanches and her rescue by her uncle and adopted brother. It took me about two days to discover, via a documentary, that the novel was based on a true story of the kidnapping of Cynthia Ann Parker in East Texas in 1836, who was held captive for 24 years and had three Comanche children. Within a few more days I discovered that both sides of the Parker family — Comanche and Texan — hold annual family reunions and send emissaries to each other’s events. I was soon on my way to Cache, Oklahoma, where the Comanches were holding theirs outside of the house built in the 1890s by Cynthia Ann’s son, Quanah.

A simple making-of-a-movie book became something much deeper and more ambitious. The research included visiting archives in Fort Sill, Lawton and Cache in Oklahoma, as well as in Canyon, Palestine, Fort Worth and Austin in Texas; interviews with historians, ethnographers and Quanah’s surviving grandson, Baldwin Parker Jr.; and road trips to the Texas Panhandle (where Quanah lived as a warrior), to Grosbeck, Texas (where Cynthia Ann was first captured) and to the Pease River (where she was later rescued). The book grew to pageantry, memory, legend.

In the Room

The main characters of both of my books were long dead, but each had a surviving widow or child who proved invaluable in helping me understand their famous relative.

For “The Searchers,” John Ford’s grandson Dan and John Wayne’s son Patrick (via email) were very helpful; Dan Ford granted me full access to his grandfather’s papers, which reside at the University of Indiana at Bloomington. Dan told me his grandfather’s personal copy of the novel “The Searchers” with handwritten notes were located in the papers, but when I arrived in Bloomington there was no record of it in the finding aid. But an enterprising librarian-archivist located the novel, which had been misfiled as a reference book in the library’s general collection. It had sat there, unseen and unread, for at least a decade.

For “High Noon,” Gary Cooper’s daughter Maria, screenwriter Carl Foreman’s widow Eve and son Jonathan, as well as producer Stanley Kramer’s widow Karen and director Fred Zinnemann’s son Tim were all generous with their time and memories. You can read endless books and articles about these famous people — and I tried to read them all — but nothing beats talking to someone who knew them intimately and can tell you how they handled adversity, what kind of music they liked and what they ate for lunch.

For “High Noon,” Gary Cooper’s daughter Maria, screenwriter Carl Foreman’s widow Eve and son Jonathan, as well as producer Stanley Kramer’s widow Karen and director Fred Zinnemann’s son Tim were all generous with their time and memories. You can read endless books and articles about these famous people — and I tried to read them all — but nothing beats talking to someone who knew them intimately and can tell you how they handled adversity, what kind of music they liked and what they ate for lunch.

Foreman, a former Communist Party member who was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in September 1951, during the middle of the film shoot, emerged as my main character. His relatives led me to a series of extensive interviews he did with his old friend and fellow writer John Weaver. Foreman had planned to use the tapes in writing his autobiography, but he died before he got started. I also got access to interviews recorded for a documentary film a decade earlier with Foreman’s first wife and a dozen friends and colleagues, most of whom had passed away in the years since. All of these materials helped me understand the ordeal Foreman faced when he had to choose between cooperating with the committee’s star chamber investigation of alleged Communist infiltration of the motion picture industry or sacrificing his very promising career. It was as if he was in the room with me explaining his actions and his terrible dilemma.

Paper Trail

I always launch a book project expecting to find new material, no matter how long ago the events I’m writing about took place.

There had been many fine books written about the committee and the Hollywood blacklist, but most had preceded the opening of many of the committee’s most sensitive documents due to the 50-year rule for confidential materials. Since 2001, the National Archives has released 94 boxes of the committee’s executive session transcripts, 89 boxes of investigative materials and 682 linear feet of “File and Reference” records, but few researchers had examined them in detail. Also, I had the advantage of focusing on a central character who had not been written about in any detail before. Anyone whose life had touched Carl Foreman’s in those years was fair game for my narrative inquiry.

One of the more intriguing and pivotal witnesses during the 1951 hearings was screenwriter and former Communist Party member Martin Berkeley. He had named at least 189 people as Communists and fellow travelers — including Foreman — during various public hearings and executive sessions. Berkeley had seldom been interviewed by the news media during those years, and left Hollywood soon after the hearings and died without having written his own account. The National Archives in Washington had three transcripts of Berkeley’s executive sessions that had never been published before. I also located his son Bill in North Carolina and interviewed him by phone, and also focused on propaganda pieces Berkeley had written for anti-Communist publications after his testimony. With these materials I was able to write the first extensive portrait of Berkeley and his role as chief informer and cheerleader for the blacklist.

Another crucial document I uncovered at the National Archives was the transcript of Foreman’s executive session in 1957, in which he admitted that he regretted his former membership in the party. For years, rumor and speculation claimed Foreman had named names during the session in order to escape the blacklist and be allowed to work in Hollywood again — something he always denied. The transcript supported his account.

A Perfect Day

A Perfect Day

Archives are wonderful places with the mission to preserve and make available historical materials. I’ve grown inordinately fond of the film studies collections held by the Margaret Herrick Library of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, UCLA, the University of Southern California, the British Film Institute in London and the New York Public Library’s Theater Arts branch at Lincoln Center. They’ve often got drafts of early scripts, letters, contracts and memos. The Hedda Hopper Papers at the Margaret Herrick Library, for example, has scrapbooks of all her right-wing gossip columns plus endless notes with salacious details and political slander. But I usually begin not with the files themselves, but with the dedicated people who work at these archives, most of whom consider it their duty to help serious researchers. These days many finding aids and indexes are available online. But archivists have often helped me locate stuff that isn’t listed in the finding aid.

For instance, with the help of Ned Comstock, a renowned archivist at USC’s Doheny Library, I was able to locate tapes of never-transcribed interviews with three major participants in the making of “High Noon.” One of them proved remarkable — a 90-minute 1973 interview with Stanley Kramer in which Kramer conceded for the first and only time I’m aware of that he had not played the dominant role in producing and editing “High Noon,” and that he could not explain why the movie was such a critical and box-office success over and above the distinguished films he had made.

Let me close by recalling one of my favorite research experiences for the “Searchers” book. I spent the morning at UCLA’s Special Collections room with Dan LeMay and his younger sister Mollie, pouring through 23 boxes of papers from their father, novelist Alan LeMay. When we finished, we got in the car for a tour of the various houses they’d lived in with their parents over the years as Alan’s career as a novelist and screenwriter gained momentum. We finished up at a house in Pacific Palisades, where the owner graciously allowed us to explore the room where their father had written much of “The Searchers.”

That’s my perfect day — visiting with people, places and papers, all in the search for a great story.

Glenn Frankel won a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting at The Washington Post and taught journalism at Stanford University and the University of Texas at Austin, where he directed the School of Journalism. His book The Searchers was a national bestseller and named a Library Journal top ten book of the year. His new book project is about New York in the 1960s and the making of “Midnight Cowboy.”