In a world which is becoming increasingly complex to navigate with the rapid changes that technology has brought, all readers (including journalists) are faced with the increased presence of “fake news” and the difficulty of identifying it.

“Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts,” the late US Senator Patrick Moynihan once said. Today, telling the difference between the two is even more challenging.

Bellingcat, the investigative journalism outfit that began as a one-man show under journalist Eliot Higgins‘ pseudonym of Brown Moses, has become a reference point for accuracy and investigative journalism, breaking numerous cases from the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 to investigations into the chemical attacks in Syria and the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in the United Kingdom.

The group’s name refers to a fable about a group of mice that decide to place a bell around the neck of a cat to protect themselves. Initially crowdfunded, the website is now supported by donors such as the Open Society Foundations, and by the workshops it holds for journalists, human rights groups and others interested in open source intelligence gathering.

The New Arab recently talked to Higgins about what motivated him to start the website, how developing technology is playing a crucial role in disinformation platforms and fake news and what can be done to counter it. (Editor’s note: Higgins was recently named one of Foreign Policy’s Global Thinkers for 2019, and Bellingcat is one of GIJN’s 173 member organizations worldwide.)

Bellingcat has shown what is possible by combining different journalistic skills with new technologies. How do you see this evolving?

It’s about taking the promise of the digitally networked society and making something of it beyond everyone getting mad at each other on social media. We are focusing on two areas now: the use of open source investigations in justice and accountability efforts, and building an open source investigation community focused on local issues. To do this, a wide range of individuals and organizations are needed, not just focused on journalism, but potentially benefiting journalism by creating new ways to find and investigate stories coming from communities that are closely engaged in certain topics.

(Since 2012, as Brown Moses, Higgins had been investigating chemical attacks in Syria using new technology which included the use of Google Earth, Street View and maps which provided imagery previously not available, in addition to the analysis of online videos. This led to findings which linked the attacks to Bashar al-Assad’s government.)

How did you conduct the investigative OSINT work on the Syrian chemical attacks in Ghouta?

There were a number of small online communities sharing information and ideas about the attack at the time: arms control communities, open source communities and others. I had gained experience specifically on the munitions being used because I had been tracking it before. When the first videos surfaced online I had plenty of material to share with these groups, which produced more ideas and theories. So it was a collaborative process, even back then.

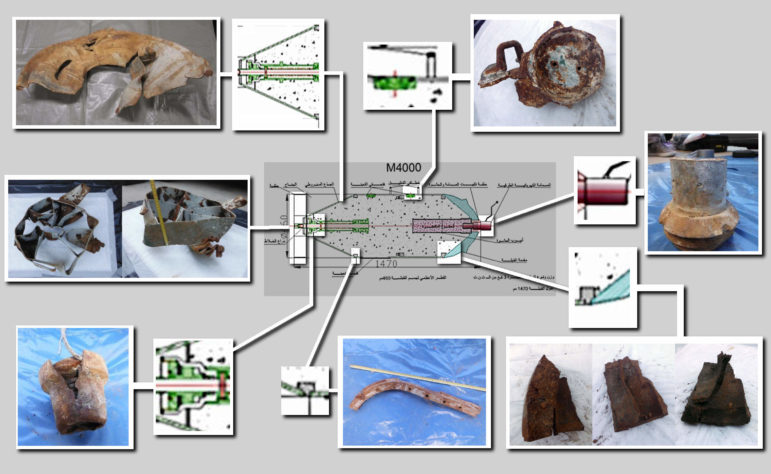

Debris found at a sarin attack site in Syria matched features visible in the diagram of an M4000 bomb. Image: Bellingcat

How did you manage to break investigative stories in Ukraine and, more recently, in Yemen?

With Ukraine, our work started with the crash of Malaysia flight (MH17), which was brought down by an SA-11 Buk missile on July 17, 2014 while flying over the country, killing 298 people.

During that investigation we found other avenues to explore, such as the presence of Russian soldiers and military equipment in Ukraine, cross-border artillery attacks from Russia, and even the activities of GRU (the foreign military intelligence agency of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation) agents in Ukraine, which made it clear that the claims of Russian involvement in Ukraine were true.

On August 9, 2018, a bomb struck a busy market area in the center of Dahyan, Saada Governorate, Yemen, killing 54 civilians, 44 of which were children. Following this strike the Saudi-led coalition spokesperson, Turki al-Malki, stated that they had hit a “legitimate military target,” as a response to a ballistic missile fired into Saudi Arabia the previous day.

However, as indicated in the Bellingcat article, this statement was disproved through video footage from inside the bus prior to the strike. It showed children crammed on the bus with few adults and no military personnel. Bellingcat proceeded to verify that the size of the bus in the video was consistent with photos of its wreckage taken after the airstrike, which was followed by additional cross-referencing with satellite images from Dahayan which showed no obvious military presence of the Houthi rebels there.

More recently we’ve been working with groups focused on the conflict in Yemen, and that involves training local groups, creating networks of organizations and, in the long term, improving the quality of reporting on Yemen.

How can you verify the authenticity and the origins of the videos you analyze?

A key part of verification is finding the origin of the image. With Reverse Image Search on Google and other services, it’s possible to do that with single images, but currently it is not possible with videos.

What this means is that it’s easier to get away with using a mis-attributed video than a mis-attributed photograph. If Reverse Image Search for videos were possible it would allow the same level of accuracy that we now have for pictures.

Have you ever incorrectly analyzed something that made you fine-tune the way you conduct research?

I’m sure if you ask the Russian government they’d say it was all wrong, but I’ve always been careful to state exactly what I know, and what the limits are of what can be known from the material we are examining.

My biggest concern is the risk of cyber attacks to our website and emails. The CyberBerkut, believed to be backed by the Russian government, hacked one of the contributor accounts on our website, and Fancy Bear, which is believed to be the GRU, has sent me and other Bellingcat team members dozens of phishing emails in an attempt to access our personal Gmail accounts. Fortunately, they failed. This is a greater concern than my physical safety.

Who makes up your team and what are their key skills?

Generally it’s the right level of obsessiveness to stick to a subject; those who have the drive to spend hours digging through material just because it’s something that interests them. Self-motivation is very important in this work. The contributors who make up our investigative team are experienced investigators; we’ve been doing this work since 2014 and our members have a broad range of experience. We also engage often with experts, learning from them and including their contributions in our work.

In the case of Russia, we’ve known journalists from The Insider (a crowdfunded citizen journalism news website) for a while and we found it beneficial to work with them on various projects as they have on-the-ground presence in Russia. We support their investigations with our open source research, which makes it a mutually beneficial and complementary relationship with a deep level of trust.

Bellingcat also receives tips and information from citizen journalists and volunteers, which are then fact-checked by the investigative journalism network staff, who are well-versed in exploiting social media and OSINT, and who are able to connect the dots that more traditional journalism might miss.

This post first appeared on The New Arab website and is reproduced here with permission.

Gaja Pellegrini-Bettoli is a freelance journalist based in Beirut. She has covered the Mosul offensive from the ground and since 2016 has made over 50 guest appearances as a Middle East analyst on Italy’s Mediaset TV. A former communications officer for the UN in Gaza, she has also worked for European institutions in Brussels.

Gaja Pellegrini-Bettoli is a freelance journalist based in Beirut. She has covered the Mosul offensive from the ground and since 2016 has made over 50 guest appearances as a Middle East analyst on Italy’s Mediaset TV. A former communications officer for the UN in Gaza, she has also worked for European institutions in Brussels.