I discovered investigative reporting while still in school, and decided it was my calling. But I also wanted to travel the world, try new things and experiment with different mediums — signals that pointed me to freelancing.

But what does it mean to freelance as an investigative reporter?

Freelancers get paid upon publication, but investigations can take up to a year to produce, or longer. These days, a story will often net well under $1,000 for deeply reported, longform articles. On the other hand, a salaried American reporter averages around $50,000 a year. You can see the disparity.

And besides money, there’s the issue of time. Living in the US state of Louisiana, I have a bottomless font of government accountability and public service stories I could produce, if I had the time. The phrase “time is money” is more brutally true for freelancers than almost anyone else.

After a few years of trying to map investigative stories against a freelance reality, I came up with a framework I refer to as “tiers.”

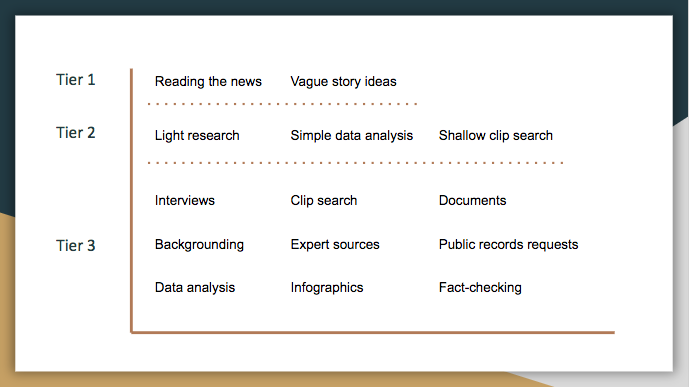

Tier 1 is just vague story ideas or things bouncing around in my brain from local news stories. Tier 2 is a bit more digging, and Tier 3 is basically the whole investigation. Think of it like breaking ground for a new building.

If an idea strikes my fancy enough, or if I think it has potential, I will take it to Tier 2. The key to Tier 2 is that it’s basic digging, no more. In this stage, I’ll examine one or two sources that will shed some light on the issue. For instance, I’ll pull some data and do a quick analysis to see if it shows anything interesting.

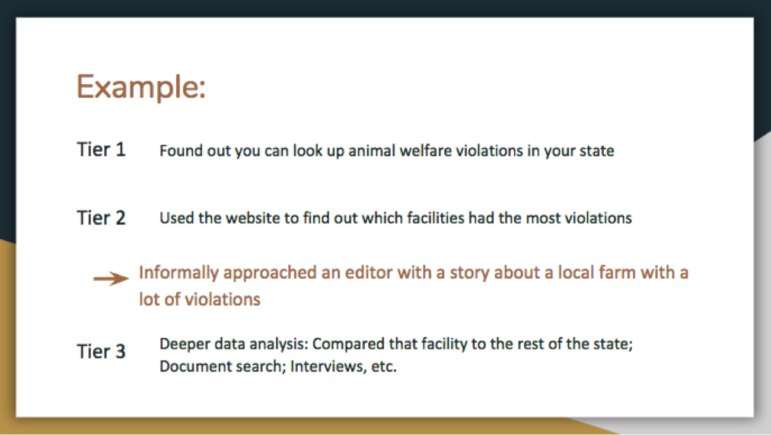

Here’s an example: I read that in the US you can get data from a national agency on animal welfare violations. I headed over to the agency’s website and downloaded the data for my state. Then I sorted it in order of violations — the sum total of my data analysis. Lo and behold, one of the worst spots in the state was an exotic animal farm in my college town.

At this point, the story is in Tier 2, so I pause. I don’t go to Tier 3 until I’ve got at the very least interest from an editor.

The reasoning for this is pretty clear: I don’t want to delve all the way in — interviews, public records, even travel costs — if I’m going to end up with nothing. If I don’t get a signed contract, or at least interest from an editor, I will drop the story.

That can be harder than it sounds. As a reporter, it’s sometimes harder to not do a story than to do it. But the less time you spend on inconsequential projects, the more you can spend on consequential ones.

The Tier 1 ideas typically come from reading the local news, hearing about stories that other reporters have done, or ongoing relationships with sources.

Tier 2 can also show that there’s not much of a “there” there. I pulled up a tax filing for a local arts nonprofit that I thought was slightly sketchy. I didn’t have to pay for the document, or even file a formal request — I just downloaded it from a website. The report showed some interesting stats (they don’t pay artists very much, apparently, even though they pull big-name musicians), but nothing pinged me as a full-blown story. So I dropped it and moved on.

With the animal violations story, I did find something good — exotic animals, bad actors, a local business — so I reached out to an old editor of mine. He said he was interested.

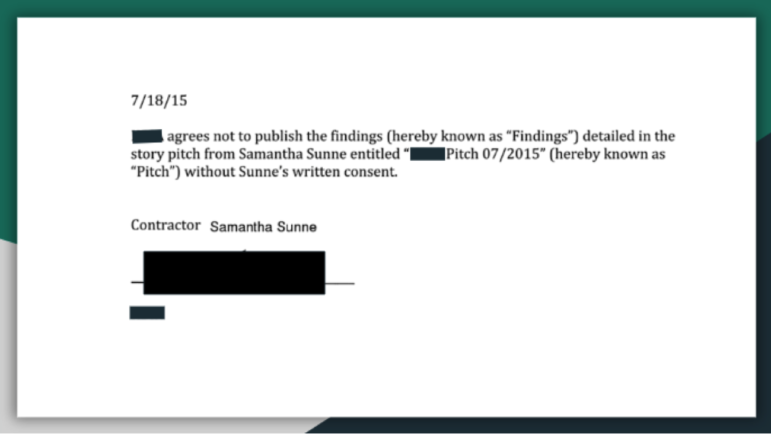

With this particular project, I went a step further and asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). In the US, an NDA is a formal agreement to keep the information shared between two parties. A very short agreement — even just a sentence! — can be legally binding as long as both parties agree in writing.

This gets to another pitfall of investigative freelancing: How do you pitch a story without giving the whole thing away? I’ve heard horror stories from other freelancers about outlets that turned down their story pitch, and then published the story using their in-house writers.

Luckily, agreements can be legally binding even if they aren’t spelled out with legalese. This is the sum total of the NDA I asked my editor to sign:

He was nice enough — and we had enough rapport — that he printed out the paragraph, signed it, scanned it and sent it back to me. In the future, I would just have us both agree to the terms via email.

An NDA might be overkill, depending on the project. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it for every story, because I tried it again with an editor I had never worked with before, and he simply turned me down.

Finally, once I’ve secured that contract or interest, I’ll move on to Tier 3, reporting the rest of the story. That way if I’m spending money on copying fees, doing face-to-face interviews or even committing a serious amount of time, at least I’m doing it with the strong likelihood that it will get published.

A very important piece to this puzzle is grants. Many organizations, like the Fund for Investigative Journalism or the International Women’s Media Foundation, are aware of the dilemma for freelance investigative journalists. They design their grants to keep reporters funded up until the point of pitching to publications. You can learn more about grants and fellowships from GIJN’s Resource Center.

Of course, the funding model and pitching tiers are going to look different for every project and every reporter. What’s your process for handling stories without a payday or publication guarantee? Let me know on samanthasunne@gmail.com.

Samantha Sunne is a freelance reporter in New Orleans, Louisiana, where she writes data and investigative stories. She also teaches digital tools to journalists around the world and publishes a newsletter called Tools for Reporters.