Collecting the pieces: Sociologist Andrés Suárez explains the challenges experienced in the process of building the Observatory of Memory and Conflict. Photo: Ginna Morelo

For five years, about 100 people processed 10,236 datasets from 592 sources and documented 353,531 facts for the Memory and Conflict Observatory, a project that seeks to document the violent events that occurred during the Colombian war. The results can be summarized into a shocking number: 262,197 fatalities over 60 years.

The project also reviewed individual stories, one by one, to provide a more complete perspective of the country’s memory and history of conflict.

The latest research now includes who did what to whom, when, where and how, starting in 1958 through July 2018. The project was led by a 41-year-old sociologist from the National University, Andrés Fernando Suárez, who is the founder of the Memory and Conflict Observatory at the National Center of Historical Memory, with researcher Gonzalo Sánchez.

The work of summarizing the violent events that occurred in Colombia faced a major challenge early on — the team had to first list what needed to be told.

“We published the report “Enough!” in 2013 and some relatives of victims told us, ‘We are not there,'” says Suárez. “So we worked, expanded our research and generated an answer.”

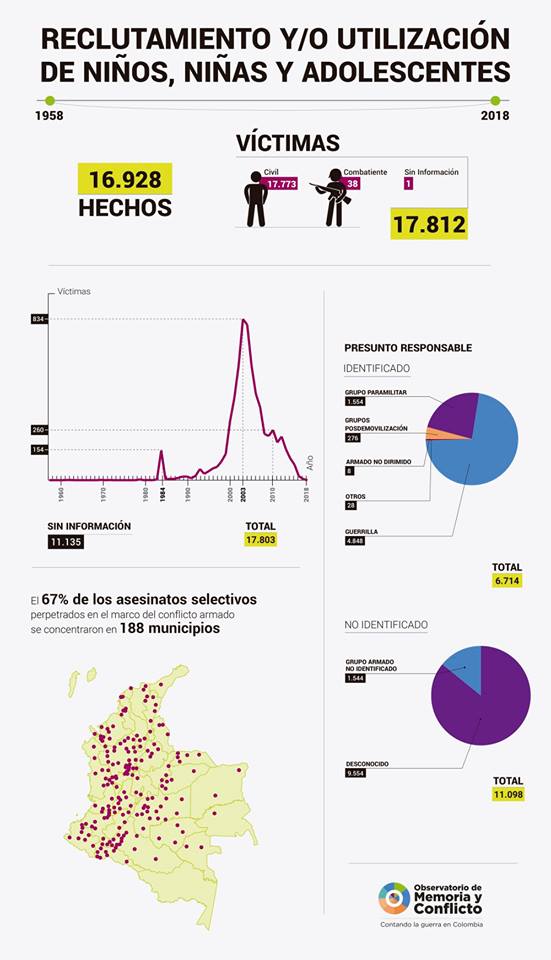

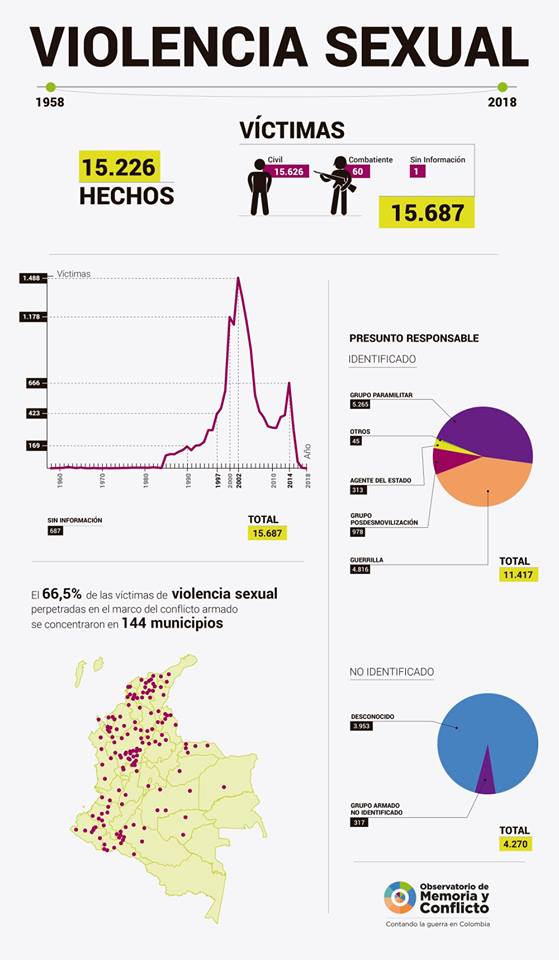

The latest research has logged the 46,533 victims of the armed conflict and the damage to civilian property; the 178,056 victims of selective assassinations or executions; the 80,514 enforced disappearances; the 37,094 of victims of kidnapping; the 15,687 victims of sexual violence; the 24,518 victims of massacres; the 1,532 victims of attacks on populations; the 748 fatal victims of terrorist attacks and the 3,686 injured; the 17,812 victims of recruitment of children and adolescents; and the 9,597 victims of antipersonnel mines.

Source and graphics: Observatory of Memory and Conflict.

The project sought out conflict data provided to Colombia’s Truth Commission, Search Unit and Special Justice for Peace. Suárez, who prefers to remain behind the scenes, explained the implications of the project in this interview:

Why did you decide to work on this project?

We saw the public interest generated by the fact that 220,000 people were reported dead, according to the “Enough!” report. When President Juan Manuel Santos received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016, we were very surprised to find out that the head of the prize committee had read our numbers. So we decided to document more cases and to create databases; we felt a responsibility and a need to do that. But behind each number there is a story and a name, and now we have all that information at the Center.

What challenges did you face with so many sources of conflict information with such different data?

We had to fight against the fragmentation of information, which not only meant that it was in many places, but there were barriers to accessing and sharing it. In Colombia there is a very strong tendency to keep information private, including public records. There are access to information laws, but vetoes are sometimes used to prevent it. There are organizations which provide figures, but you cannot tell where they got their information from — they do not share their sources.

What about civil society?

In civil society we also saw many efforts, but it was also fragmented. There are tensions and mistrust between NGOs and also between NGOs and the state. The different sorts of data is what generates confusion in society.

Source and graphics: Observatory of Memory and Conflict

Throughout the investigation, what surprised you most about the victims?

Seeing the way grandmothers cling to their newborn grandchildren. Without the new life that came, that person would not have been able to continue. Death took away a lot, but their grandchildren give them a link to the world, an anchor. The second thing is that, in religion, the victims found a balm for life.

You also investigated disappearances. What stories had an impact on you?

The stories which delved into everything that was done to search for those “disappeared” victims, including when we would go to talk to armed groups; how people were humiliated; how the armed groups affronted the dignity of relatives by saying: “Do not look for that person anymore, we threw him into the river.” Or, “You are already a widow, get yourself a new home, start a new life.” There was a succession of very painful humiliations that we did not know about.

There is a story that I will never forget, which is about an area controlled by an armed group where, if a relative wanted to visit, the armed group had to be given advance notice so the visitor could enter the place without risk. In one story, a man was not warned about this. They stopped him at the checkpoint and killed him. They did not try to find out who this stranger in the territory was, they just killed him.

This post first appeared on the website of El Tiempo, and is cross-posted here with permission.

Ginna Morelo is president of Colombia’s association of investigative journalists, GIJN member Consejo de Redacción, and also currently serves as editor at El Tiempo’s Data Unit. Consejo de Redacción co-hosts, with IPYS and Transparency International, the Conferencia Latinoamericana de Periodismo de Investigación (COLPIN) on November 8 to 11 in Bogota.

Ginna Morelo is president of Colombia’s association of investigative journalists, GIJN member Consejo de Redacción, and also currently serves as editor at El Tiempo’s Data Unit. Consejo de Redacción co-hosts, with IPYS and Transparency International, the Conferencia Latinoamericana de Periodismo de Investigación (COLPIN) on November 8 to 11 in Bogota.