The Whistleblower: Edward Snowden

Holger Stark and his colleagues have broken global, policy-changing stories, thanks to the proactive courage of whistleblowers like Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning.

But these journalists had to wait, passively, for those mass surveillance disclosures. And Stark, the investigations director at Die Zeit, recalls at least three occasions where potential whistleblowers have withdrawn and his own major stories have collapsed because he and his colleagues lacked the knowledge and resources to guarantee the legal, physical, reputational or psychological cover his sources needed to release their bombshells.

In response, a new investigative journalism model has launched as an organized effort to separate the responsibility for the welfare of at-risk sources from the responsibility for the content they provide, so that reporters can focus wholly on their own areas of expertise.

Protecting Whistleblowers

Set up by The Signals Network – a San Francisco-based nonprofit formed in 2017 to support whistleblowers — the model involves a collaboration between the investigative teams at The Telegraph, Die Zeit, The Intercept, Mediapart and WikiTribune.

In the model’s pilot project – launched in late June – the five media groups have called for whistleblowers to use the project’s secure communications system to report on the misuse of big data, a notably broad subject that they chose in a vote at a meeting organized by Signals in March.

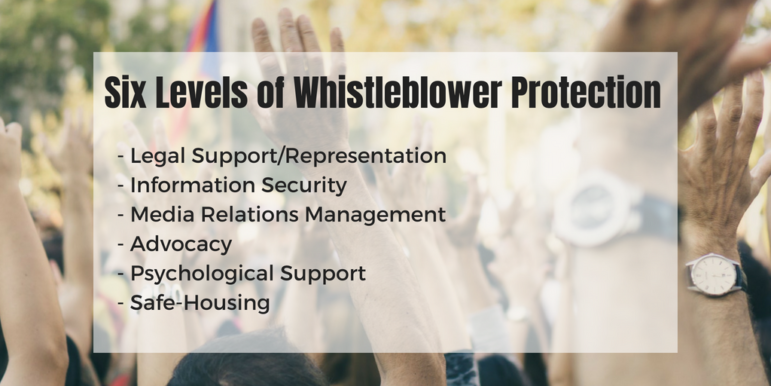

According to Delphine Halgand, executive director at The Signals Network, the parties made formal agreements about a co-embargo, a rotational system to monitor a shared encryption information system and the use of Signals’ resources which, they say, offer six levels of whistleblower protection.

Halgand, however, conceded that not all invited media signed on to the project.

And interviews with two of the media parties revealed the two central unknowns of the project: which of the myriad big data sectors might be tackled and, in general, how the five media groups will actually work together in verifying and reporting the incoming claims.

And interviews with two of the media parties revealed the two central unknowns of the project: which of the myriad big data sectors might be tackled and, in general, how the five media groups will actually work together in verifying and reporting the incoming claims.

Here is how the overall architecture is supposed to work:

For the pre-reporting phase, the five media groups make themed calls inviting whistleblowers to make disclosures on encrypted channels; the groups take turns monitoring the incoming messages; and they can refer sources, on request, to a list of pro bono lawyers provided by Signals. For the reporting phase, Signals remains strictly uninvolved, while the five news organizations – having received the disclosures simultaneously – choose stories and reporting strategies collaboratively. In the post-publication phase, the 30 journalists within the collaboration step away, and the Signals Network steps in to actively support the whistleblowers with their legal, emotional, logistical and PR needs.

“In the past, (investigative teams) were like a one-stop shop – where the journalists were also the guys who had to handle or at least try to pass on all the legal problems, personal problems and logistical challenges facing these potential sources,” said Stark. “For example, I worked with the Chelsea Manning documents in 2010, when I coordinated Der Spiegel’s coverage of the diplomatic cables on Iraq and Afghanistan and, in 2013, I worked with the Snowden documents. In those cases, we had to deal with whistleblowers facing astonishingly complex pressures, and as journalists we found it overwhelming. In this case that Signals has established, we have separated those two fields. It’s a really remarkable idea.”

Collaborating for Impact

In an impact incentive for whistleblowers, the model offers a potential combined audience of 46 million readers and users between the five groups, although Halgand said individual partners could elect not to publish.

Doug Haddix, executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE), said the project “offers a promising approach to tackle a complex story.”

Stories run by each media partner will likely be different, with agreed-upon pieces then contextualized to their local markets; the groups currently hold a weekly call.

Dedicated to creating “a proactive dynamic toward whistleblowers,” The Signals Network is registered as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit in the US — and is currently seeking equivalent status in France – and was founded on the belief that “we need more whistleblowers to build a more transparent society … (and that) those who risk their lives and livelihoods to bring us the truth deserve our support.”

Its founder, entrepreneur Gilles Raymond, provided seed funding of around $300,000 for the group after his second media venture, News Republic, was acquired for $57 million.

The nonprofit claims to offer whistleblowers six levels of protection post-publication, including legal help, PR, safe housing, advocacy and counseling. And it has provided the five media partners, and potential whistleblowers, with two channels of secure communication: an encrypted app and an email system featuring PGP encryption. All five media partners have included the app on their home pages, where they have also broadcast the call for sources.

Jimmy Wales – founder of WikiTribune and co-founder of Wikipedia – said he was confident in the security of the twin systems: “Nothing is perfect, or impenetrable, (but) strong encryption is one of the most important tools that we have … and they are using the right tools.”

Jimmy Wales – founder of WikiTribune and co-founder of Wikipedia – said he was confident in the security of the twin systems: “Nothing is perfect, or impenetrable, (but) strong encryption is one of the most important tools that we have … and they are using the right tools.”

Halgand said the foundation has set up a network of pro bono lawyers with expertise in public interest disclosure, including Ben Wizner, Snowden’s lead attorney, and William Bourdon, who has acted for several high-profile European sources. She said that – to their surprise – whistleblowers consulted on the project indicated that psychological and emotional support represented key unaddressed needs.

Having previously served as US director for Reporters Without Borders, Halgand was involved in the release of Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian in Iran and worked closely with the family of imprisoned CIA whistleblower Jeffrey Sterling. Referring to her motivation for joining The Signals Network, Halgand recalled her frustration in highlighting the injustice and lack of help suffered by Sterling with this emotional summation: “And nobody cared.”

Snowden has also voiced support for the project in a statement which, Halgand said, he insisted include concerns about the existing ad hoc infrastructure facing whistleblowers: “When I came forward in 2013, sources had to try and patch together this kind of reporting infrastructure journalist by journalist, in total secrecy, and with crude tools … The Signals Network is sending a message to whistleblowers that this time, the newsroom is ready.”

However, the architecture of the model involves some fascinating legal wrinkles.

According to Halgand, while the five media partners will initially refer whistleblowers to a list of local pro bono lawyers provided by Signals, the nonprofit is to actively engage with whistleblowers only after publication in order to protect identities.

“This preserves the privileged relationship for the source with the journalist and lawyer; we don’t want to be a potential weakness in any legal case, in terms of protecting identities,” she said. “Post-publication — and especially once their identity is known — it is much easier for us to provide psychological support, legal support, PR management and so on.”

Starting with Big Data

Meanwhile, Stark revealed that the exact wording of the “Big Data Call” – the message now broadcast by all five media – was the subject of intense legal wrangling, due to statute differences between the countries that are home to the media partners. Language that might have been fine in Europe, he said, needed to be pared back out of concern that US prosecutors might deem that language an incitement to commit a crime, or illegally breach a contract. And so all five media now simply “welcome(s) information from whistleblowers within the technology industry,” and there is no mention in the joint call for “confidential documents,” for instance.

Halgand said a “second call” on a new subject – and possibly involving new media partners – could take place this fall.

She revealed that the finalized pilot project was born at a late winter meeting in France, in which representatives of more than half a dozen news outlets were invited to submit three subject areas that they felt would most benefit from a source-protection media collaboration that featured an active call to whistleblowers. Halgand said abuses in the pharmaceuticals industry and government corruption featured on many lists, but that the misuse of big data was the area common to all.

Of course, leaks on the abuse of big data – including illegal surveillance and invasions of consumer privacy – have already characterized some of the most dramatic recent media investigations.

Indeed, Halgand said, “It is notable that this choice was made just two weeks before the Cambridge Analytica scandal exploded.”

And the Signals Network’s pilot project call is remarkably open-ended, “whether the data in question is being used for social media, marketing, healthcare, law enforcement, machine learning/AI … or, for example, why companies have chosen specific product updates and their effect on consumers.”

“Our interest is not just with the big tech firms like Google and Microsoft,” said Stark. “For instance, the big car companies and the automotive insurance companies are collecting a huge amount of data about people; way beyond traditional business models. There is the sensitive data that health insurers possess. And personal voice assistants monitor almost everything. We’ve spoken to prosecutors who speak of this like it’s a new gold era for investigation. So the project has no limits here.”

Rowan Philp is a multiple award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.

Rowan Philp is a multiple award-winning journalist who has worked in more than two dozen countries. Currently based in Boston, Philp was the chief reporter and London bureau chief for South Africa’s Sunday Times for 15 years.