Promises Checked: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s election promises are tracked by a fact-checking site based in Canada. Photo: Tasnim News Agency, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When he talks about fact-checking, Farhad Souzanchi alternates between a stony face and wide grin. But two weeks ago, he was almost all smiles.

In a hotel ballroom in Toronto, Souzanchi — who uses an alias to protect his identity — led a conversation about misinformation during the December and January protests throughout Iran. He showed off a beta version of a new fact-checking chatbot he created for Telegram, a hugely popular messaging app that was recently blocked in Iran. He was in his element.

“It’s one of those things that I didn’t know I was passionate about, but I was,” Souzanchi said about fact-checking. “When I was in Iran, I was kind of annoying among my friends by constant, simple Googling.”

“Have you seen the meme that says, ‘Hey, come to bed’ and the character is someone on the internet? That was me.”

About 100 people from civil society organizations, media outlets and technology companies gathered at the Iran Cyber Dialogue (ICD) on May 14 and 15 to discuss how to deal with government censorship and address geopolitical obstacles like the Iran nuclear deal. In the past, ICD helped inspire ASL19, a digital rights organization that hosts the event, to create its own fact-checking projects after learning from The Washington Post Fact Checker and Morsi Meter at the 2015 ICD.

“That obviously helped us, by being exposed to their work, developing our own projects. That’s when we realized we can do fact-checking as well,” said Souzanchi, a research manager at ASL19.

As the front of a notebook passed out to ICD participants read: “There is always a way.”

Fact-Checking Authoritarians

The fact that anyone has managed to fact-check Iranian politics at all is perhaps surprising.

ASL19 hosts Fact-Nameh and Rouhani Meter — the latter keeping tabs on how Iran President Hassan Rouhani treats his campaign promises while the former fact-checks statements and debunks viral hoaxes. Since launching Rouhani Meter in 2013, Souzanchi has learned a lot about how to fact-check a repressive regime.

For starters, being based in Toronto instead of Tehran — where Freedom House says there’s no press freedom — helps.

“It can get dangerous. In Iran, proving a statement made by the leader wrong is not like fact-checking the US president — it’s a totally different thing,” he said. “We couldn’t do this if we were inside the country. We couldn’t address certain promises and issues easily the way we do it here if we were inside Iran. We would have to watch out for the red lines or risk harsh reaction from the government.”

Keeping Tabs: Rouhanimeter tracks how Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani treats his campaign promises. Screenshot: Rouhanimeter.com

The tactic of fact-checking a regime from outside its borders — executed by Rouhani Meter and Fact-Nameh, which both remain unblocked in Iran despite rating claims false and promises unachieved for President Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei — may be key for getting fact-checking off the ground in other repressive regimes around the world, where the format has either failed or never been introduced in the first place.

According to the Reporters’ Lab, of the approximately 150 fact-checking projects worldwide, none is currently operating in Russia, where the government openly controls the mainstream media, and North Korea, where a free press doesn’t exist. In China, one fact-checking project covers health misinformation while steering clear of politics — a taboo subject in a country where censorship is the norm.

“Access to publicly held information is often impossible for a reporter, therefore political fact-checking is moot,” said Robert Mahoney, deputy executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, in an email. “Power in authoritarian countries is about control of information. Getting around those controls is a major challenge for the independent press.”

Alternative Sourcing and Distribution Methods

So how can fact-checkers make headway? Aside from being located outside of the regimes themselves, Souzanchi said they should consider alternative methods of sourcing and distribution.

“One thing that we did was ask people to participate in terms of suggesting us topics. That’s one thing that we did and was well-received,” he said. “They’re always constantly suggesting stuff for us to fact-check.”

Distribution Plan: Fact-Nameh relies on messaging app Telegram to reach its audience in Iran. Screenshot: Fact-Nameh.com

Although it’s still blocked inside Iran, Telegram is still a major part of Fact-Nameh’s distribution and sourcing strategy. In the same way that fact-checkers around the world rely on users to send them viral hoaxes from WhatsApp groups and distribute their resulting fact checks, Souzanchi said Fact-Nameh has leaned on Telegram as a key tool for reaching its audience in Iran — where mainstream social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram have consistently been blocked.

Still, it can be hard to find an audience. Ershad Alijani, an Iranian journalist for France 24, said that, while ASL19’s fact-checking sites have had more success than most, they’re still limited in their reach among Iranians.

“Fact-checking is a ‘fancy’ product still in Iran — maybe like everywhere in the world — so their impact is limited to a very thin part of society: educated, well-connected and passionate about the ‘facts,’” he said. “Despite the professionalism that Fact-Nameh or Rouhani Meter or the others have in this field, the impact of fact-checking is very limited in Iran unfortunately.”

Alijani compared Fact-Nameh’s social media following (more than 4,000 on Twitter and more than 6,000 on Telegram) to the myriad disparate accounts that publish fake news on a regular basis. Because of fact checks’ inability to scale, he said he commonly sees debunked stories circulating in Telegram groups ranging from hundreds of thousands of members to small groups of his family and friends.

Transparency Is the Key

Keeping a Watchful Eye: Two fact-checking sites keep tabs on the accuracy of statements by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Photo: Flickr

Meanwhile, in Turkey — which Freedom House also says has no press freedom — two fact-checking organizations have sprouted up. Teyit and Doğruluk Payı have both doggedly covered the regime, keeping tabs on the accuracy of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s statements in a country that CPJ says has more journalists in prison than anywhere else in the world.

So what’s their secret? Baybars Örsek said it all comes down to transparency.

“Turkey has never been a friendly environment for journalism in general, and the current political atmosphere in the country is absolutely a higher level in terms of challenges experienced by journalists,” said the founder of Doğruluk Payı.

“All of our fact checks are sent automatically to all political actors, no matter what our scorecard indicates. Having this sort of a proactive communications strategy has enabled us to have the space we utterly need.”

Gülin Çavuş, a journalist at Teyit (and a 2017 International Fact-Checking Network fellow), agreed. Her advice for fact-checkers when their transparent methodology isn’t enough is to consider self-censorship so that they can continue to operate.

“Staying alive and surviving is the most important strategy in order not to risk yourselves and your organization,” she said. “It may sometimes be the best solution to postpone some of the projects and topics you desire to do, but you consider dangerous, to periods in which more democratic and freer press.”

In spite of their separate challenges, both the Turkish fact-checkers and ASL19’s sites have at least been able to get fact-checking projects off the ground. That’s a harder sell in China — job security, surveillance, harassment, lawsuits and arrests are all huge barriers for journalists there.

“We should keep in mind that politicians in China are not elected through a fully democratic process,” said Masato Kajimoto, an assistant professor of practice at the Journalism & Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong. “Also, promise-tracking requires documented records and data that are trustworthy, which do not exist in China in many areas.”

Learning from Other Projects

Promising Start: ZimFact launched in Zimbabwe in March to fact-check political claims. Screenshot: Zimfact.org.

ASL19’s fact-checking sites aren’t the first — or even the latest — to cover a repressive regime.

In Zimbabwe, another country that Freedom House says has little press freedom, ZimFact launched in March with support from the Swedish Fojo Media Institute at Linnaeus University. The project aims to fact-check political claims and previously told Poynter that it was concerned with government censorship.

“The new administration has so far been exhibiting a position of Zimbabwe being open for business,” said Jean Mujati, the Zimbabwe program manager for Fojo. “The environment so far has been welcoming to the idea of a fact-checking project and stories from the platform are therefore being used in both print and online publications.”

On a continent with several authoritarian regimes, ZimFact is a rarity. According to the Reporters’ Lab’s database, Africa Check is one of the only other fact-checking organizations in the region — and for good reason.

“There are a number of places in Africa where I think it would be very hard, if not impossible, for fact-checkers to operate,” said executive director Peter Cunliffe-Jones. “Eritrea, Ethiopia, even countries like Rwanda have — if you look at the records of things like the Committee to Protect Journalists — a very poor record on media freedom.”

And that manifests in myriad barriers to entry for prospective fact-checkers, such as registering with the government, prospective detentions and raids for publishing political content online. In Tanzania, the government is close to passing an approximately $920 fee for bloggers — in a country with a nominal per capita income of less than $900.

However, breakthroughs are possible.

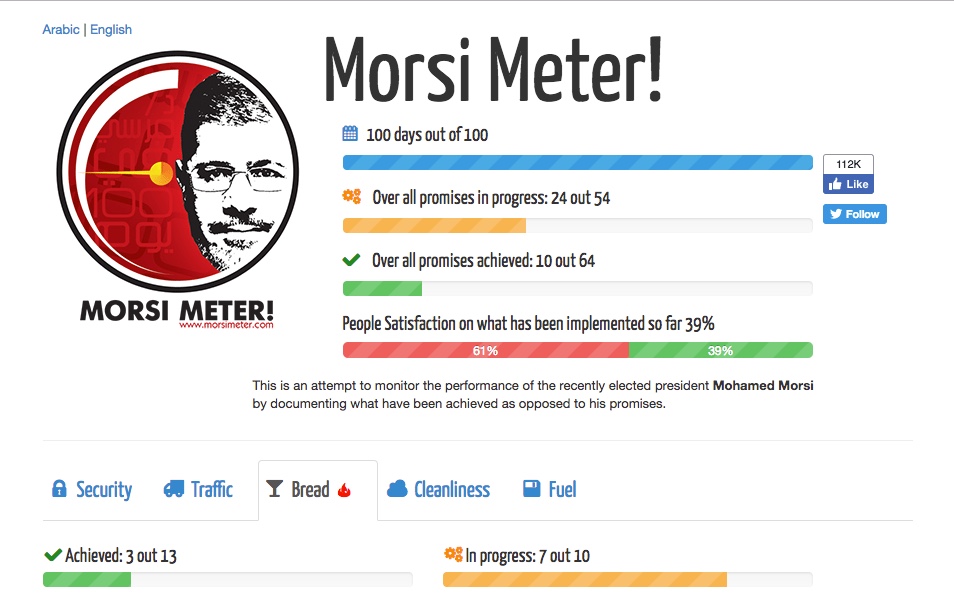

Good Timing: The Morsi Meter was launched during the Arab Spring to keep Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi accountable and lasted for his first 100 days in office. Screenshot: Morsi Meter

In 2012, Morsi Meter launched amid the ongoing Arab Spring in order to keep the then-newly elected Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi accountable for his promises. Inspired by PolitiFact’s Obameter, the project operated with support from Zabatak, a now-offline nonprofit group aimed at ridding Egypt of corruption.

But figuring out the means of distribution and coverage isn’t enough to guarantee a fact-checker’s success in a regime like Egypt, which Freedom House also says has no press freedom. It has to come at the right time.

“Something like this in the Middle East is extremely dangerous,” said Abbas Adel, founder of Morsi Meter. “We took the risk and were anonymous at the beginning but eventually the media and public attention gave us the power to challenge the president publicly.”

Once that happened, the project worked fairly seamlessly for Morsi’s first 100 days in office — in spite of partisan attacks from other media outlets and conspiracies that Morsi Meter was funded by foreign intelligence officials, Adel said.

“It actually worked pretty well, because the timing was right,” said Amr Sobhy, an Egyptian information activist who worked on Morsi Meter. “The website was well-received by all local media and has helped traditional media focus on the first 100 days mission. The presidency also at that time dealt with the website as legitimate accountability effort.”

The project ended after Morsi’s first 100 days and no fact-checking outlet has taken its place since. But other fact-checking projects in authoritarian countries are lucky to even start — and it might have as much to do with the regime itself as with its effect on prospective audiences.

Making an Impact

In 2015, Alexey Kovalev launched a fact-checking site called Noodle Remover, a play on a Russian expression that equates lying to putting noodles in someone’s ears. But he gave up after a while because of a lack of interest. His most popular debunk got about 150,000 page views in a country with about 90 million internet users, and he said he didn’t see his fact checks have any discernible impact.

“To be honest, I just don’t have any time for it or any will to carry on,” said Kovalev, who’s now managing editor of Coda Story. “I was speaking to a very small part of the population that is aware enough to know that much of the news they’re consuming is state-related.”

“Even though some of my articles that I posted on my project received dozens of thousands of views, it did very little to have any significant impact on the discourse. If anything, there’s even more manipulation and fake news in the Russian media right now.”

The flagrance of state propaganda in Russia can be jarring to Americans. But for Russians, it’s common — so common that Kovalev said Russians approach any kind of media with a healthy dose of skepticism that carries over to even the most objective news outlets.

With that in mind, Kovalev said there’s a critical need for more fact-checking to sort through what’s bunk.

Organizations outside the country like Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty have tried their hand at debunking. But foreign media are a hard sell for Russians. Some domestic projects are making small strides, such as The Insider, an investigative news site that publishes a weekly debunking section. But still, Kovalev said the project struggles to maintain an audience that needs fact checks in the first place.

“Nothing comes even close to becoming a single authority that everyone would trust — that’s why I think fact-checking is so politicized,” he said. “There isn’t a single journalist that everyone in Russia, on all sides of the aisle, trusts.”

Ongoing Challenges

While some strategies for fact-checking oppressive regimes can be the difference between publication and censorship, they also can cause headaches for fact-checkers.

Souzanchi said that while being based in Toronto is a major reason why he’s able to fact-check the Iranian government, it also makes some readers doubt their credibility. To them, location matters.

“‘We don’t know what’s going on because we’re not based in Iran or we’re just foreign agents.’ People might not say it, but that’s always an obstacle for us,” he said. “We try to get around it by being open about our sources and being straightforward in our arguments so that you can see it for yourself.”

In Russia’s case, a domestic fact-checking project is not only preferable — it could be essential for success. Kovalev said that any incoming fact-checking organization would have to be located within the country in order to get buy-in from prospective audiences.

“Even in a politically-minded segment of the population, there’s a distrust of foreigners telling us what’s fake news and what’s not,” he said. “I don’t think there’s any market for (foreign) fact checks in Russia. Why would Russians trust foreigners telling them what’s true and what’s not?”

Meanwhile, in China, Kajimoto said the only viable strategy he could envision for political fact-checking would be to set up an organization operating outside the country. But even that approach is flawed.

“I don’t think real, independent political fact-checking is possible within China,” he said. “One strategy may be to establish an organization in a foreign country but then you will likely be blocked by the Great Firewall and won’t be able to reach people in China that way.”

Coming Under Attack

When a fact-checker does manage to launch and establish an audience, blowback can be severe. Alijani said that receiving harsh criticism on social media is a fact of life for fact-checkers covering Iranian politics.

“Fact-checkers are under attack by extremists on both sides — supporters of the regime and opposition groups. I’ve been a victim of these attacks as well,” he said. “I’ve heard from some colleagues that they just gave up a fact-checking article because they did not want to become a target of these attacks and trolls on the social media.”

Souzanchi said that, after launching Rouhani Meter, the site was soon blocked by the government and readers had to use virtual private networks (VPNs) to access it — a circumvention tool that’s become a daily reality for Iranians who want to access an uncensored internet.

“And then some articles came out, especially coming from some more hardline groups, conservative hardliners, talking about how we’re a puppet of the CIA and that kind of stuff,” he said. “That was the first reaction from the government.”

Rouhani Meter has since been unblocked and adds new features to its site every few months or so. And, according to Souzanchi, it has an impact.

In the past few years, he said there’s been a bigger focus from both sides of the Iranian political spectrum on Rouhani’s promises — one that didn’t exist before Rouhani Meter. During the past election year, Souzanchi said he saw people citing the promise-tracker on social media. Once Rouhani’s own Twitter account even tweeted about a promise that Rouhani Meter rated, using their own language in the process.

“These small things are signs that we’re seeing, and the fact that he’s constantly talking about how he hasn’t forgotten his promises — this repeating of doing good on promises — hasn’t died out,” he said. “I think Rouhani Meter has played a part in that in terms of always being present in this conversation about the government’s actions.”

Even despots understand the power of fact-checking.

This article was first published by Poynter.org and is cross-posted with permission

Daniel Funke covers fact-checking, online misinformation and fake news for the International Fact-Checking Network at The Poynter Institute. He previously reported for Poynter as a Google News Lab Fellow and has worked for the Los Angeles Times, USA Today and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Daniel Funke covers fact-checking, online misinformation and fake news for the International Fact-Checking Network at The Poynter Institute. He previously reported for Poynter as a Google News Lab Fellow and has worked for the Los Angeles Times, USA Today and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.