Picturing It: Getting a story to unfold in images requires planning. Photo: Kaique Rocha, Pexels

As we noted yesterday, in previous columns for Mojo Workin’ I’ve written about mojo equipment, sound recording and editing on a smartphone. In one sense, I left out the best and most frustrating bit — developing and producing the story. So, here is part two of two, which focuses on equipment, coverage, and audio perspective.

Equipment Focus

The smartphone is a Swiss Army knife on steroids, in media terms, a creative suite in a pocket. The Mojo Kit will vary depending on the job and the region. In the Middle East and North Africa you wouldn’t have large kits because they’re too obvious. Sabbagh, a former Reuters correspondent and editor of the Jordan Times, says working small can be an advantage because it enables press to “work and move in oppressive situations where citizens and policemen can obstruct the work of journalists and where large cameras paint them as targets.”

Using a smart device properly is not always easy, and it takes some practice to effectively use powerful apps. The type of app you use is often determined by the story you need to tell. So, experiment with apps and make your own informed decision based on the job at hand (see: Essential Mobile Journalism Tools).

Coverage Focus

Video stories, even investigative ones, need pictures. There are two types of coverage — that which you set up and actuality, which doesn’t need to be set up.

Bromwell’s approach to filming with his phone is influenced by his work as a video journalist: “I shoot sequences, lots of close-ups; steady, well-composed shots, no pans, tilts or zooms.”

My experience working as a producer and cameraman on current affairs shoots in difficult regions, is that you won’t always pull out your tripod, which could also paint you as a target and slow your work rate. Of course, tripods are handy for long interviews and long, wide pans and that long-lens close-up. But much of your work will be hand held, so practice hand-held skills when working wide and close on a wide lens.

My tip: Press your elbows into your sides and hold the smartphone with two hands. This triangle creates added stability in much the same way that a smartphone cradle, like a Beastgrip, does. (Yes, it feels like a Dalek, at first.)

My tip: Press your elbows into your sides and hold the smartphone with two hands. This triangle creates added stability in much the same way that a smartphone cradle, like a Beastgrip, does. (Yes, it feels like a Dalek, at first.)

Irrespective of the type of coverage, it’s important to consider these questions:

- How will the story be set up? A dramatic close up, a telling wide shot, dynamic B-roll actuality, narration, an interview grab or a combination?

- What B roll is required to introduce interviewees, to cover edits in the interview and accentuate interview points?

- What B roll will you use to cover narration?

- What B roll and interviews are needed to give the story currency?

- How will you end the story finish and what vision and audio is required for this?

- Are you prepared to react to location inputs?

Following are a couple of templates for thinking about coverage.

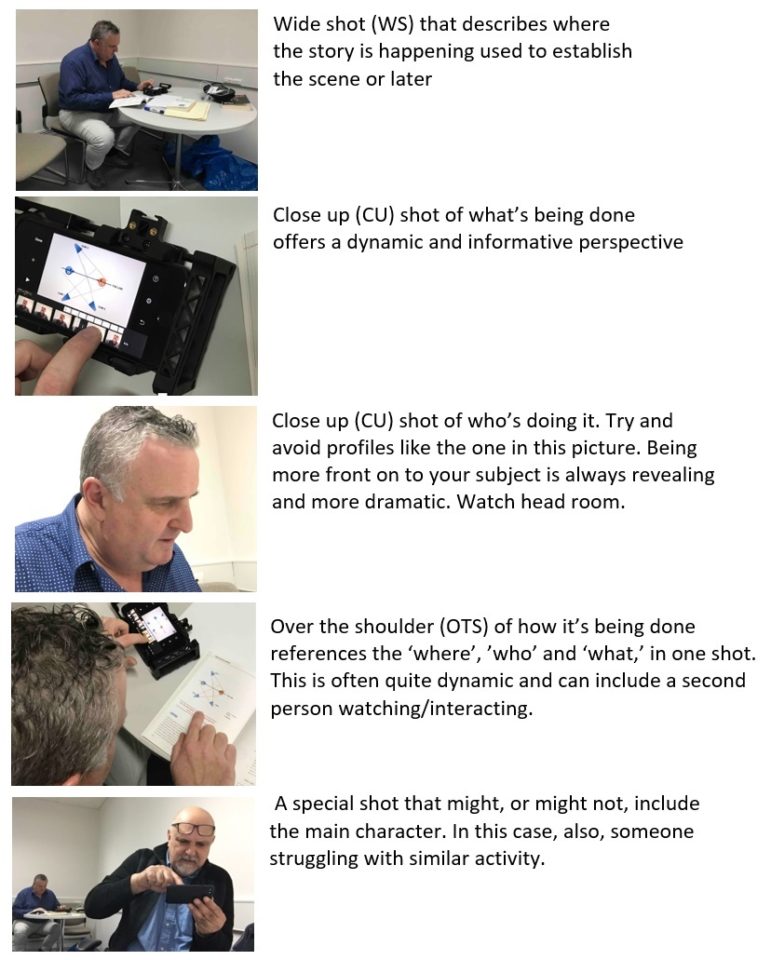

The classic five-shot rule, edited in the order that’s most effective. This template could be used to cover simple activity and a localized event.

The order in which shots are edited will give the piece its unique resonance. How shots are juxtaposed with narration and other elements gives the piece its pace and gravitas.

The order in which shots are edited will give the piece its unique resonance. How shots are juxtaposed with narration and other elements gives the piece its pace and gravitas.

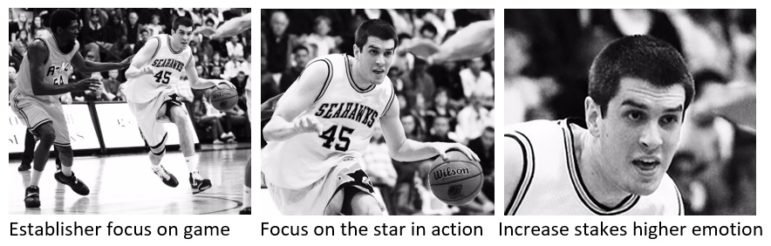

Take a look at these three shots. It is the same shot cropped. Each frame provides a different feel. So choosing your framing is essential to telling the story.

Add an interview, narration, relevant B roll and, if you’ve planned right, completed SCRAP, and captured some “emotion,” you’ll have a strong story to edit.

The five types of shot that form a sequence, plus the main interview and narration, will tell your basic story. But your story may have anything from five to 13 sequences, each identified by the style of shot(s) and a structural role. When planning these shots/sequences, whenever possible, it’s best to consider them in the order they might be edited. Hence, my tip is to learn sequence coverage by filming something that has a definite process and structure.

For example, practice filming someone cooking pasta, making eggs and bacon, or using a lathe to shape a block of wood into a table leg — how many different sequences are required to cover each of the above activities?

Bromwell says, “I always encourage people to do the simple things well if they want to achieve a polished piece.” Simple process shoots, where structure is evident, enable you to concentrate on coverage and, in particular, sequencing — emotion, information, B roll, interviews and the elements required to shorten a 30-minute process, into a powerful two-minute film.

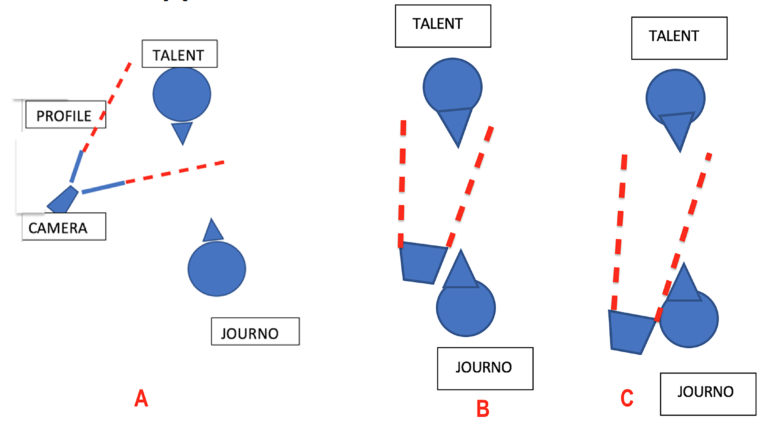

Understanding eye line is important. If you are setting up for a single camera location interview, you might consider the front on eye line set up in (B). In many regions it is quite acceptable to hold the camera in front — at chest or waist height — and have the interviewee respond over the camera. Other times it needs to be at eye level (B). In this case it’s difficult to shoot completely from the front because you might lose eye contact with the interviewee. In this case, place the camera as close to front as possible, and place the journalist (mojo) next to the lens (B). This is traditional location interview eye line. You would not, as has been suggested, have the camera sit behind your eye line (C), especially if you are working solo; this is done when working with a camera person, who can check the frame.

Understanding eye line is important. If you are setting up for a single camera location interview, you might consider the front on eye line set up in (B). In many regions it is quite acceptable to hold the camera in front — at chest or waist height — and have the interviewee respond over the camera. Other times it needs to be at eye level (B). In this case it’s difficult to shoot completely from the front because you might lose eye contact with the interviewee. In this case, place the camera as close to front as possible, and place the journalist (mojo) next to the lens (B). This is traditional location interview eye line. You would not, as has been suggested, have the camera sit behind your eye line (C), especially if you are working solo; this is done when working with a camera person, who can check the frame.

If you need the shot to be profile (A), it can be, but avoid profile shots for the following reasons:

- You get more variety of shots, without moving, if you shoot from the front.

- You can move the camera in on the wide lens.

- You can even zoom for a close up (not advisable unless imperative).

The front-on shot (or almost front on) is more powerful because you see the person’s face, their eyes and therefore their emotion, all without moving the camera away from their eye line.

Here are a few tips for shooting shots and sequences:

- Switch the smartphone to airplane mode to avoid unwanted calls and WiFi interference.

- Make sure your battery is charged.

- Make sure you have space on your phone.

- Let someone know where and when you will film.

- Use a plan to indicate clearly what you have filmed and how much is left to film; this will help during the shoot and during the edit.

- Prepare specific research and questions for your interviewee and set these out against your structure, so you know how they might be used in the story edit.

- Shoot with the light over your shoulder and on the subject.

- Don’t use the tripod unless you have to.

- Learn to hand hold the shot smoothly, something that is helped by using a wide lens. For stability create a V with your smartphone, hands and your elbows locked into your body (see figure above).

- Always switch the camera on and wait for the counter to roll before you ask questions, so as not to miss the beginning of the answer.

- Ask open-ended questions that don’t give you a yes or no answer, unless you want yes or no.

- Frame your interviewee in medium close-up unless they move their hands about, in which case choose a medium shot.

- Try and hold B-roll shots for 10 seconds to ensure they are steady and to enable multiple sections of the shot to be used.

- Always shoot a few seconds of static shot before and after a panning shot so your pan is steady at both ends and so you end up with three potential shots.

Shoot B roll before the interview, for example, as you enter a building, during actuality with interviewees and immediately after to record interview-specific B roll.

Shoot B roll before the interview, for example, as you enter a building, during actuality with interviewees and immediately after to record interview-specific B roll.- When it gets busy, think about information and not the shots — so think “story.”

- Movement within a frame, or that which is created by moving the camera, can create more dynamic shots. Be careful to be steady.

- Be aware of screen direction and the 180-degree rule, but learn how to break rules by using, for example, neutral close-up shots.

- Use the correct gear (see: Essential Mobile Journalism Tools)

Questions that should be considered are:

- How will interviews and narration create story bounce?

- How much B roll and what type do you need to set the scene, cover interview edits, and highlight and shorten specific moments? Don’t forget the detail, or location-setting shots. When you feel you have enough B roll, get more.

- Do you need additional audio, like a buzz track of the atmosphere in a room? This is usually recorded for at least 30 seconds and used to cover and smooth contrasting audio edits.

- Will graphics be required and how and where will these come from — created on your device or imported using Airstash or AirDrop?

- If it’s a historical piece, or an update, will archive be used and where will this come from, will it be copyright cleared and will it cost?

- Will stand-ups be needed and if so, why? Stand-ups can be effective when there is no B roll, interviews or actuality and to establish the journalist in location.

When shooting a stand-up keep the script short, one thought per sentence and one sentence per paragraph. Choose a key word for each paragraph. Roll into a retake without buttoning off. If there is a problem, it’s in the script. If you fix the script and still fluff it, put a sharp stone in your shoe and when your concentration is on the stone, record the piece to camera.

Audio Perspective

Recording audio in the field is about being ready with the right microphones and a sound strategy to enable you to react to location inputs. The recording task is made more complex because mojos predominantly work on their own. Renowned journalist and radio mojo pioneer, Neal Augenstein, from Washington, DC-all-news radio station WTOP, concluded that speaking into a built-in microphone on the iPhone was “approximately 92 percent as good as using an industry Shure mic.”

Augustine also found that by the time audio travels through “the broadcast processing chain,” its inferior quality “was not noticeable to the listener.” This is important to remember especially when working fast and when the location is not noisy and when the recorder, in this case a smart device, is close to the sound source. While possible with radio or audio-type journalism, placement can become increasingly difficult with video journalism (see: Recording Sound on a Smartphone).

My Tip: If you need translation, do it in the field, just in case pick-ups are needed, which you won’t know until the translation is completed.

I’d suggest:

- Always have a shotgun mic attached to your phone and a lapel mic in the bag.

- If you need an interviewee to walk and talk, use a radio mic (see: Microphone 101).

- If you need your questions cleaner, use a splitter and mic yourself with a lapel mic. Remember that both the interviewee’s and interviewer’s microphones will generally be recorded onto the same track on your smartphone.

- If you need a true split track, use a device like a Zoom H1 to record a second track (use a clap) and sync the two tracks in the edit (see: DIY radio microphone).

In summary, video stories are more than radio with pictures. Understanding the rubric nature of combining video elements to create a seamless story is a key step in the mojo workflow. As Bromwell says, “You need a certain discipline in your approach to successfully bring everything together.”

Working as a mojo is a holistic and organized process. You need to be smart and ready to react to location inputs. You need to think and work like a journalist. You need to focus, record and edit the story like a filmmaker. Staying ethically and legally healthy and understanding the technology – but not being limited by it – is also part of the job. Knowing how to do all this is difficult, but the control it provides mojos over their stories is uplifting. Give it a go and you’ll grin broadly at the possibility. Go mojo.

For past Mojo Workin’ columns, and more, see the GIJN resource page on mobile journalism.

Ivo Burum is an Australia-based journalist and award-winning television producer with over 30 years experience producing 2,500 hours of prime-time programming. A mobile journalism pioneer, Ivo runs the Burum Media consultancy and is a coordinator of Media Industries at La Trobe Univ.

Ivo Burum is an Australia-based journalist and award-winning television producer with over 30 years experience producing 2,500 hours of prime-time programming. A mobile journalism pioneer, Ivo runs the Burum Media consultancy and is a coordinator of Media Industries at La Trobe Univ.