Picturing It: Getting a story to unfold in images requires planning. Photo: Kaique Rocha, Pexels

In previous columns for Mojo Workin’, I wrote about mojo equipment, sound recording and editing on a smartphone. In one sense, I left out the best and most frustrating bit — developing and producing the story. So, here goes. This first part focuses on developing your idea and having a story and investigative focus. Part two, tomorrow, focuses on equipment, coverage, and audio perspective.

In 2007, for those working in TV, the advent of the iPhone was a game changer. It became apparent, at least to me, that mobile technology would redefine the way we produced TV content. Even the way we did investigative video journalism. It was a lightbulb moment.

In 1993, while working in television, I began producing a self-shot TV series that gave our audience an opportunity to be part of the production process. Participants learned to use digital video cameras to tell their own personal stories. By 2010, they were using smartphones and could complete the whole production process on their phone, including the all-important edit.

“A journalist in today’s digital world will have no edge if he can’t use mojo,” says Rana Sabbagh, GIJN board member and director of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism. “Especially journalists in the Arab world where the state, politicians and agenda-driven publishers try to muzzle media and free speech.”

Nearly all types of video stories can be shot and edited using a smartphone. But working solo has drawbacks as well as advantages.

Recently, acclaimed director Steven Soderbergh shot a feature on his iPhone, adding that he’d shoot all his future films using a smartphone. Soderbergh’s reasoning, apart from technical excellence, was that it gave him the freedom to work outside the studio system. This is also true for investigative and citizen journalists who use smartphones to create complete stories.

Sabbagh sees these journalists, who are often first on the scene, as bearing “witness to a first draft of history.” She believes their mobile investigations can provide “the prima facie evidence at international criminal tribunals,” potentially providing a level of editorial control essential to achieving transparency and accountability.

Following are some development and workflow points investigative journalists might consider when working in the mobile story space.

Developing Your Idea

Choose a topic and, before deciding on the story that will best convey your idea, ask:

- What’s the investigative focus? What’s the topic and how will I make it?

- Who’s the audience? Who’s watching, what is the demographic, what’s the political and the cultural imperative?

- What’s the angle? Why is the story being told, what’s the focus and how will this be best achieved creatively and editorially?

- What’s the style? Is it current affairs form, a series of short stories, a long investigative exposé, narration or interviewee driven?

- What’s the structure? what is the beginning, middle and end; who will speak when and what elements will be required to support the story structure?

Investigative Focus

From the get-go, as Mark Lee Hunter at INSEAD‘s Social Innovation Centre suggests, it’s imperative to ask what your thesis, or research question, will investigate. “We use stories as the cement which holds together every step of the investigative process, from conception to research, writing, quality control and publication,” Hunter says.

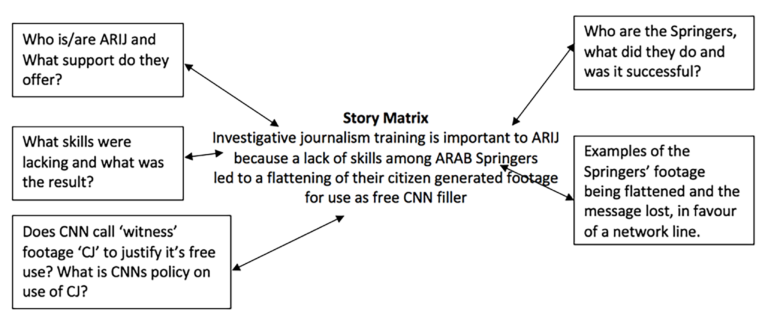

Following is a simple example of a story statement, which Hunter might call “a hypothesis,” and the various investigations that might be asked around its research question:

Not unlike a current affairs-level of inquiry, an investigative focus insists that story dictates technology and workflow.

Phillip Bromwell, a video journalist from Ireland’s RTE who works in the mobile space, says: “My job requires me to tell stories, and we have to remember the audience doesn’t really care how content is created, but they will engage with a good story.”

Bromwell’s focus on the story, ahead of the technology behind it, is important.

“Although I can film and I can edit, my primary skill is as a storyteller,” he says. “I am certainly not a ‘techie’ and I am not as obsessed as others are with having the very latest piece of mojo gear.”

He’s right — allowing story to dictate the right technology for a specific job is also important. For example, shooting a story on lions in Africa may require a hybrid DSLR and long lens kit to be able to shoot the required shots from a distance, so as not to get eaten. Conversely, in war-torn Aleppo, a small mojo kit can make a journalist less of a target.

The Story Focus

So how do you find the story? As Hunter says, “You need to follow your passion.” That’s a perfect start. Before asking if the story is worth the investigative effort, you have to consider who’s affected, how much are they suffering, can that be shown, is there a journey, are there bad guys and/or good guys and do we have access?

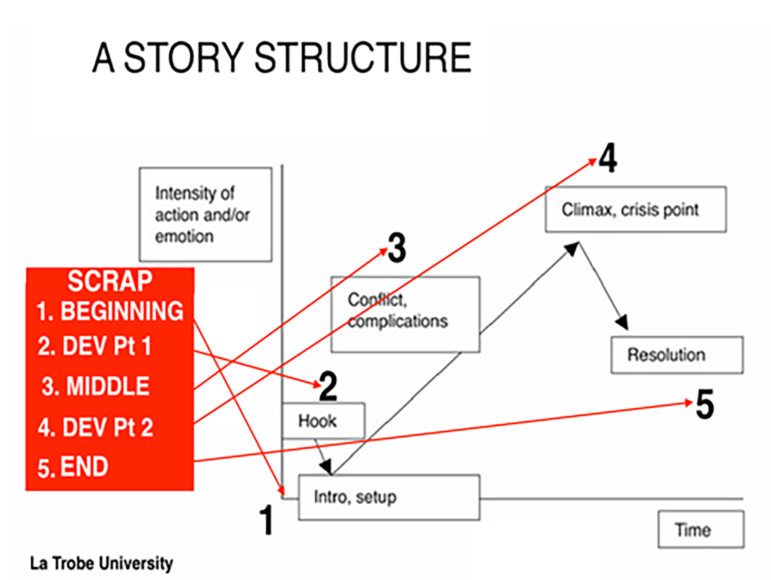

As the concept gets more of a story focus, complete a more specific SCRAP check list:

- Story: what is it?

- Characters: who is best to tell it?

- Resolution: what’s the structure and why?

- Actuality: what will be filmed and why?

- Production: where is it happening, what are the logistics and how will I produce it?

SCRAP helps answer journalism’s 5Ws — who, what, when, where and why.

Next, I create a simple five- to seven-point edit plan — a structural road map of how my story might go. The following road map articulates the various plot points and my story bounce and acts as an on-location story and character checklist, and the beginning of my edit plan (see: Editing on a Smartphone).

I continue to answer my 5Ws:

I continue to answer my 5Ws:

- What/who will I film and how?

- Where and when will I film?

- Why did it happen and why am I producing this story?

Shooting video is more cumbersome than writing a print story. A plan keeps you on schedule. It is a checklist to help decide if everything is covered before wrapping location.

Finally, to understand the relationship between your mobile story and its audience consider the following:

- Currency of the story.

- Significance of the story will be impacted by its Currency.

- Proximity of the story will impact Significance.

- Prominence of story talent can trump Proximity.

- Human interest can increase with Prominence.

A Character Focus

Knowing who, what and how much to film is important when planning a mojo video production. For example, we can’t ring someone for a quick phone interview — they need to be on camera, so managing time and expectations is critical.

Notwithstanding this, mojo news stories may be breaking, so therefore unplanned. In this situation it’s even more important to quickly ascertain a story focus to determine the best characters/interviewees to help tell the story.

For example, who do I interview at the scene of an accident and, importantly, who do I interview first? Can I ask the ambulance driver for a comment while he is inserting an IV line into an injured person’s arm? If not, how do I cover this as B roll, so that I can ask my questions when the paramedic is free? What’s most relevant in a breaking story at, let’s say, a Bosnian war grave? More bodies, longer interviews with a witness or the man with photographs of his missing family, who he believes are among the dead? Do I need it all? If so, how will I include it all in a short video story? The best way to decide who’s relevant is to:

- Map your potential interviewees against your structural story notes (see plan above) and your audience.

Once you decide on your interviewees, go back and adjust your story structure to plan accordingly, and consider the following story character notes:

- When will we hear from the main interviewee and will that be as actuality or interview?

- Which interviewee will be used to develop the story, or will you use B roll and narration?

- Who will I use to tell the climax and how will I create this?

- Who will I use and how will I close the story?

- Do I have clearance?

- Do I have B roll to introduce my interviewees?

You can generally work the above out at the research stage, pre-interviews and once you begin mapping your structure. Because real research happens on the ground, and because things change, you need to understand your options and be prepared to shift your views on location. That’s where a simple structural plan helps.

My Tip: If it’s a choice between a smart interviewee and an engaging one, choose the latter, if you can’t have both. You can always add the factual smarts using narration and B roll.

For past Mojo Workin’ columns, and more, see the GIJN resource page on mobile journalism.

Tomorrow, look for part two of “Developing And Producing on a Smart Phone,” focusing on equipment, coverage and audio perspective.

Ivo Burum is an Australia-based journalist and award-winning television producer with over 30 years spent producing 2,500 hours of prime-time programming. A mobile journalism pioneer, Ivo runs the Burum Media consultancy and coordinates Media Industries at La Trobe Univ.

Ivo Burum is an Australia-based journalist and award-winning television producer with over 30 years spent producing 2,500 hours of prime-time programming. A mobile journalism pioneer, Ivo runs the Burum Media consultancy and coordinates Media Industries at La Trobe Univ.