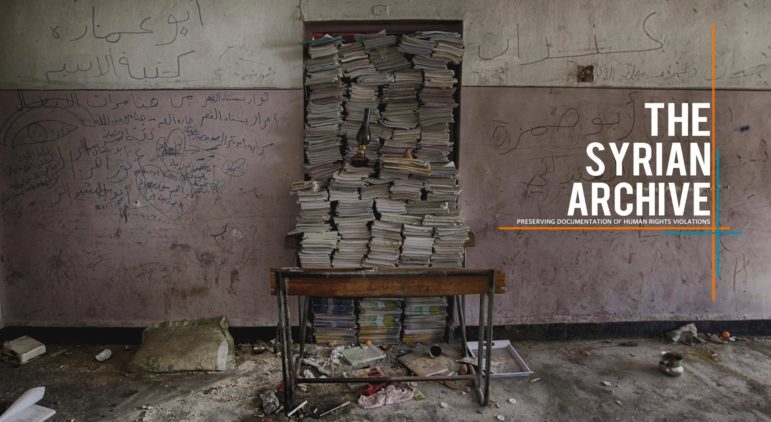

Seeing is Believing: The Syrian Archive curates documentation relating to human rights violations in Syria. Image: Muzaffar Salman via Syrian Archive Facebook

Like many of the stories coming out of Syria’s war zones, it was distressing to listen to.

“We were trying to do CPR on dead people,” Jasmeen, the survivor of a chemical weapons attack, explains at an event in Berlin, Germany. “But we did not know they were dead. Nobody knew what to do. People were having fits, as though they had epilepsy,” she pauses, searching for words. “Foaming at the mouth. I had never seen anything like it. I find it very hard to describe.”

Jasmeen, a former activist who cannot give her full name for security reasons, took part in the Syrian revolution but now lives in Berlin. She was with her family in the outer Damascus suburb of Muadamiyah on August 21, 2013, when the area was struck by chemical weapons at around 5am. Later, inspectors from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons would find sarin, a deadly nerve agent, on most of the munitions fragments recovered in Muadamiyah and the other areas targeted that night.

As Jasmeen points out, the attack on her hometown occurred exactly one year and one day after former US president Barack Obama said the ongoing use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime was a “red line” for the US. There have been many more since too, including the latest chemical weapons attack in eastern Ghouta, in which at least 42 people died.

Jasmeen is here tonight, talking about her personal experience of death and chemical weapons, at the behest of a small group of researchers also based in the German capital, known as the Syrian Archive. The group, which has been collecting, investigating and analyzing human rights violations in Syria since 2014, has just launched the world’s first publicly accessible database of chemical weapons attacks in Syria between 2012 and 2018.

Collecting the Data

It all started with the Syrian Archive’s founder, Hadi al-Khatib. While working as a project manager for an NGO called No Peace Without Justice in Gaziantep, Turkey, he had come to a worrying conclusion: Despite the fact that the Syrian crisis, which has mutated from a popular revolution in 2011 to a bloody civil war today, is widely acknowledged as the “most documented” conflict in human history, al-Khatib realized that digital reports coming out of Syria were not being catalogued or fully checked for veracity. Even worse, given that citizen journalists and first responders were risking their lives to provide the information, some reports were being lost altogether.

So when al-Khatib returned home to Berlin in 2014, he began collecting everything he could find. He started out single-handed, armed with only a few Excel sheets and open-source verification techniques — which entail using data collected from publicly available sources, like social media and maps, to cross check things like locations, sources and dates, and ensure videos and pictures are real.

Since then, the Syrian Archive has grown, in both content, recognition and professionalism, and today al-Khatib has seven colleagues in Berlin, Denmark and Turkey, between 20 and 30 specially trained student-assistants at universities around the world, including Berkeley, Hong Kong, Essex and Toronto, and over 1.5 million pieces of digital content archived, of which around 4,400 have been fact-checked. The archive’s mission statement points out that it is not on the side of any party to the Syrian conflict and that it simply tries to document all human rights violations, no matter who committed them.

The new chemical weapons database is part of that. It includes 212 verified incidents from 193 sources and 861 fact-checked videos. And there are more coming — in fact, as we spoke, al-Khatib was being sent evidence of further previously unknown attacks.

The Syrian Archive’s long-term aim is to create a database that can be used in future legal cases against the perpetrators of human rights violations. The fact that a video on Facebook can be used to convict a war criminal is not as crazy as it might once have sounded: The first case built solely around evidence from social media, against the leader of a Libyan military group, went to the International Criminal Court in the Netherlands late last year.

And al-Khatib says the Syrian Archive is already sharing information with a comparatively new body, the United Nations-mandated International Impartial, Independent Mechanism for Syria, which was set up to ensure “accountability for the horrific atrocities that have been committed in Syria.” The Syrian Archive also works with organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, providing them with information that is often included in their reports on the situation in Syria. The rights activists also provide the archive with their own verified reports, which are also included in the new database.

“Whenever you’re doing an investigation, you’re not just looking at one image or video,” says Eliot Higgins, the British founder of Bellingcat, one of the world’s most respected open-source investigation platforms, who has himself advised the International Criminal Court. “It is always part of a network of information and corroboration.”

“Relevance, authenticity and objectivity” are some of the main requirements for being able to present digital evidence in a court, Patrick Kroker, a lawyer with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, explains at the Berlin launch.

Open Data: The first publicly accessible database of chemical weapons attacks in Syria between 2012 and 2018. Screenshot

Digging In

Which is why the Syrian Archive can also be very useful to journalists. Following are five ways that investigative reporters can now dig into the new chemical weapons database.

New Stories, Leads and Unexpected Connections

“How many chemical weapons attacks have most people heard of?” Higgins asks. “Maybe five.” The Syrian Archive has documented over 200. And Higgins says he was investigating one particular 2017 attack, using the nerve agent, sarin — of which Syrian stocks were supposedly destroyed in 2014 — when he found three other chemical weapons attacks he had never even heard about. “Only two people died so they didn’t get as much attention,” he explains.

Still, he contacted sources inside Syria and it turned out they had kept remnants of bombs in the lesser known attacks. Higgins was able to find a link between the type of munitions used in those and the 2017 sarin attack in the area of Al Lataminah, that made many more headlines.

Search Your Specialty

It is possible to search the database using key words. Say, if you’re looking for attacks specifically using certain chemicals or if you’re investigating the bombing of medical facilities. Results can be sorted by relevance, date or the number of clips and reports provided for each incident. The map can be used if you want to know how many chemical weapons attacks occurred in one area.

Al-Khatib adds that some specifics — for example certain chemicals between certain dates — may only be accessible to the archive researchers themselves. In this case, he is happy to help download the required information. Just send him an e-mail (info@syrianarchive.org).

Follow the Data

Use the collated data to seek out patterns. For example, the rise and fall of casualty rates from certain types of attacks; whether bombings are random in certain areas or follow a designated schedule; or, as data reporter Lylla Younes did recently, create a timeline of suspected Russian air attacks in Syria.

Find Better Contacts

You’re looking into a certain Syrian event and you need an eye witness? Many of the videos in the archive come from either activists, citizen journalists or the local media centers that sprang up to document protests when the Syrian revolution began in 2011. Follow the archive’s documentation back to the source (a video may be reposted by others but the Syrian Archive researchers have usually traced it back to the original) and contact the eye-witness directly, via their own online accounts — for instance, a channel on YouTube or Facebook page.

Al-Khatib says the researchers at the Syrian Archive are also happy to help. Recently analysts at the archive contributed to a New York Times story on the increased targeting of medical facilities in rebel-held areas, telling journalists about changes they had seen over time with regard to this.

New Methods to Aid Your Research

Get a primer on how the Syrian Archive works with open-source intelligence (or OSINT). And to find the latest tools for doing this kind of work, check the Bellingcat site. Despite the fact that their work is accessible to everyone, the Syrian Archive restricts who can work on their own verification because of the sensitive nature of the work and potential legal ramifications. Bellingcat tends toward a more crowd-sourced approach and they update a list of tools regularly, which anyone can access.

The latest weapons in the fight against disinformation: Logo recognition software, that allows users to input an unknown logo and find out to whom it belongs, and 3D modelling, where researchers can add the model of, for example, a tank to the scenario they are researching to aid analysis.

Cathrin Schaer is a freelance journalist whose work has been published in such publications as The New York Times, the South China Morning Post, The Guardian, Spiegel Online and Vogue magazine. When not writing her own stories, she is editor-in-chief of the Iraqi current affairs website, Niqash.org.

is a freelance journalist whose work has been published in such publications as The New York Times, the South China Morning Post, The Guardian, Spiegel Online and Vogue magazine. When not writing her own stories, she is editor-in-chief of the Iraqi current affairs website, Niqash.org.