Vibrant Network: 101 Reporters works with more than 500 reporters across India.

In a building whose entrance isn’t more than three-feet wide, sharing neighborhood space with a busy public market, is the headquarters of 101 Reporters — Gangadhar Patil’s maverick venture, an online platform for journalists to pitch story ideas to be matched with publications.

The life of a freelance journalist is difficult in any part of the world and India is no exception. Payments can be irregular and editors can be unresponsive. So in October 2015, after more than four years of working with some of India’s biggest publications — The New Indian Express, DNA and The Economic Times — Patil launched 101 in Bangalore.

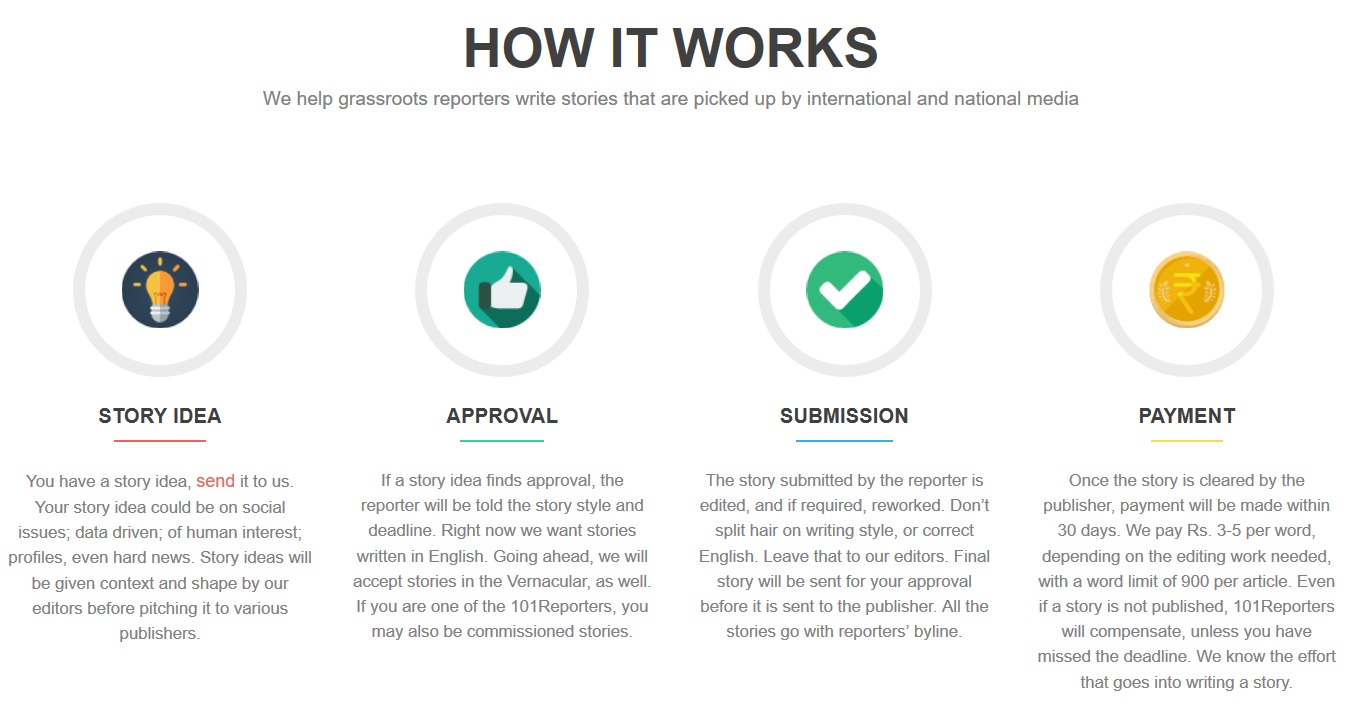

To pitch an idea using the 101 Reporters website, journalists fill out a form with details, including their story topic, why it’s important and how long they expect it will take to finish.

Although 101’s team has grown since it began, Patil personally reviews these submissions. If the idea is approved, the story is edited and pitched to a publication, to appear with the reporter’s byline. As long as the reporter makes the deadline, they are paid by 101, even if the story isn’t published.

Connections: 101 Reporters has links to 15 national and international news outlets and has a team to translate stories into English.

Patil’s career began with a two-month stint at a local television channel’s newsroom in an Indian town called Belgaum. His time in Belgaum, as well as working independently, showed Patil that reporters in small towns knew much more than “parachute journalists” from bigger media organizations who cover stories about areas and regions with which they have little experience.

“There was such a vacuum,” he says. “A journalist’s biggest skill is to source information and verify it.” However, it was difficult for mainstream publications to find the right sources.

101 Reporters is currently a vibrant network of more than 500 journalists all over India that grew organically. “Anything in isolation is not important,” says Patil, “but you can do wonders with a network.”

Saikat Datta, South Asia editor for Asia Times, says, “Because of people like Gangadhar Patil, we have solid journalism.” Asia Times has been buying stories from 101 since December 2017.

“It’s a real democratization of news,” says Datta, “which tends to be urban [and] privileged. 101 attempts to move beyond that.”

Syeda Ambia Zahan is the state editor for 101 in Northeast India, based in Assam. “Because of demography [and], topography, this is one of the least covered regions in India,” she says. “But with 101, it is possible to report stories from the ground, which even local media haven’t reported.”

The organization is partnered with about 15 national and international news outlets, which includes Nieman Lab and The Times UK, and raised approximately $125,000 during two rounds of funding in 2017 from individual donors. But it isn’t profitable yet.

Saurabh Sharma, an independent journalist in Uttar Pradesh is part of the core team of 101. He was bored at his previous job with a digital national because he wanted to be out reporting. He says that organizations like 101 are necessary for independent, unbiased journalism, particularly in an environment flooded with fake news.

“They don’t confine you to a desk,” he says, “[They] believe the story is only done by reporting on the spot.”

With 101, Sharma manages about 200 reporters across Indian states like Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Chhattisgarh. His stories have appeared in publications like CNN International and he writes on a variety of topics. He makes more than he did at a full-time job with the added bonus of being in charge of his time.

Manoj Kumar, a reporter with a Hindi newspaper in Chandigarh, has been working with 101 for the past year. He says there are many problems in mainstream media, like the financial pressure of advertisements and language requirements that are confining.

“We don’t see the commercial value of a story at 101,” he says, which allows for more stories about social issues. He also files all his stories in Hindi.

“101 has a team to translate, which makes [the process] so much easier,” he says. “[Otherwise] I couldn’t dream of publishing in English.”

Zahan explains that it is a great organization to work for as a woman. “I report on violence in remote areas,” she says. “With 101, they have such a good network and Gangadhar is in constant touch. I don’t have to worry about my safety. And it’s a gender-friendly team — they don’t discriminate between men and women for an assignment.”

Jaideep V Giridhar, executive editor at Firstpost, says 101 gives digital newsrooms in India access to reporters. “There’s only so much opinion you can write. It needs to be mounted on reportage.”

When the recent emergency was declared in Sri Lanka, for example, there was a cricket match scheduled for the same day in Colombo. Giridhar says he wasn’t sure if the match would take place so he called 101. Within an hour, 101 had found a reporter who provided live updates. “They’re very enthusiastic,” Giridhar says. “I’ve never asked [for a story] or they’ve never pitched a story and haven’t delivered.”

This post first appeared on the IJNet website and is cross-posted here with permission.

Ayesha Aleem is a freelance journalist. She was previously a features writer for Condé Nast Traveller India, correspondent for India Today and a business editor for CPI Media Group. She graduated with a master’s degree in journalism from Boston University in 2010.

Ayesha Aleem is a freelance journalist. She was previously a features writer for Condé Nast Traveller India, correspondent for India Today and a business editor for CPI Media Group. She graduated with a master’s degree in journalism from Boston University in 2010.