العربية | 中文 | Русский | Español

In the past few weeks we have confirmed that one country can indeed derail the public debate of another during a critical election period, infesting the information waters with piranha-like social media bots and fake profiles carefully crafted to deepen divisions and erode faith in democratic systems.

It’s no wonder that the media, as one of the protagonists in this muddled ecosystem, is particularly worried about losing trust. In the last two years, universities, philanthropic and non-governmental organizations and digital platforms have been developing diverse projects to study how the media loses the public’s confidence, and find practical ways to reverse this trend.

The recently published paper Bridging the Gap, Rebuilding Citizen Trust in Media, by Anya Schiffrin, director of the Technology, Media and Communication specialization of Columbia University’s School for International and Public Affairs, Beatrice Santa-Wood, Susanna de Martino, Ellen Hume and other contributors, probably offers the most complete list of the current projects around media and trust.

The recently published paper Bridging the Gap, Rebuilding Citizen Trust in Media, by Anya Schiffrin, director of the Technology, Media and Communication specialization of Columbia University’s School for International and Public Affairs, Beatrice Santa-Wood, Susanna de Martino, Ellen Hume and other contributors, probably offers the most complete list of the current projects around media and trust.

The News Integrity Initiative at CUNY University, The Ethical Journalism Network’s report Trust Factor, the Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy (whose main report will be published later this year) and the Trust Project started by the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, are some of the initiatives explained in the document. (See other projects listed below.)

But this is not the first time in the short history of mass media that people have been worried about the impact bad information could have on societies, said Bridging the Gap. This was a research topic at the end of the 19th century and again after television became massive in the 1960s. The interest then resurged in the 1980s, when the idea of “citizen journalism” was created, and media literacy was promoted as a way to bring the media and audiences closer.

After reviewing the academic literature on media and trust, the report found that there is no conclusive evidence about how trust in media is built or lost. Another key finding of this review is that “each media environment’s unique characteristics make it almost impossible to generalize across societies.” For example, liberals in the United States tend to trust media more, while in the United Kingdom it is the conservatives. Similarly, while correcting errors could consolidate trust for a newspaper in one country, it could breed more suspicion in another.

However, researchers have found some common traits. Unsurprisingly, people tend to trust media outlets that agree with their beliefs and content that seems familiar to them. This last tendency could be particularly dangerous in the internet era. For instance, if a lie is reposted so many times it becomes familiar, people begin to think it’s true.

Professor Schiffrin’s paper also explored how some individual journalistic enterprises from different parts of the world are responding to the trust challenge. Not all the 15 editors interviewed see the digital environment in the same way. For about half of them, regardless of the digital era, journalism is still fundamentally about telling the truth and therein lies their credibility. The other half thinks that indeed the honest search for truth is still at the heart of journalism, but, in the new era, they must also actively convince readers and society that they are credible.

Beyond their different views, all initiatives seem to rely on two principles to optimize trust. The first is transparency: revealing sources of funding, explaining the inner workings of newsrooms and their story selection and openly admitting mistakes, among other practices. The second is participation: giving readers a voice in editorial and business decisions, appealing to readers’ expertise when reporting, verifying and editing a story, and collaborating with other media outlets, sometimes even with competitors.

As the report points out, building quality media outlets that are both transparent and participatory takes a lot of extraordinary work and resources, which are not easy to come by these days. Could these efforts be sustainable? Or do they just provide spaces for future leaders of the field to experiment? It is too early to tell. However, editorial models like these are already saying a lot about what journalism — the trade that specializes in searching for mostly uncomfortable truths — needs to do if it wants to survive in the murky environment of disinformation.

Some Projects Around Media and Trust

News Integrity Initiative

The News Integrity Initiative announced last year is a joint effort to advance news literacy, increase trust in journalism and better inform the public conversation through grants, events, research and a network of people across sectors to share ideas and collaborate on solutions. The global consortium is focused primarily on projects that increase empathy among people with opposing viewpoints, amplify marginalized voices, cultivate diversity within news organizations and mitigate the effect of news misinformation.

TruthBuzz

Initiated in 2017 by the International Center for Journalists with support from the Craig Newmark Foundation, the TruthBuzz contest aimed to find new ways to help verified facts reach the widest possible audience. The competition sought creative solutions to take fact-checking beyond long-form explanations and bullet points, and the winning entries used humor, animation and social media campaigns to help the facts travel far and wide.

The Building Trust in Media in South East Europe and Turkey Project by the Ethical Journalism Network

Launched in 2016 in line with the guidelines for EU support of media freedom and media integrity in the enlargement countries, the project seeks to build trust and restore confidence in the media in Southeast Europe and Turkey through:

- Supporting self-regulation mechanisms and the inclusion of professional standards, freedom of expression and media integrity in the basic education of journalists;

- Improving the internal governance of media organizations through the implementation of internal rules and good practices that recognize human rights and labor standards, as well as improved levels of transparency in ownership, management and administration and the enforcement of ethical codes within media outlets;

- Increasing public demand for quality media and empowering citizens through media literacy.

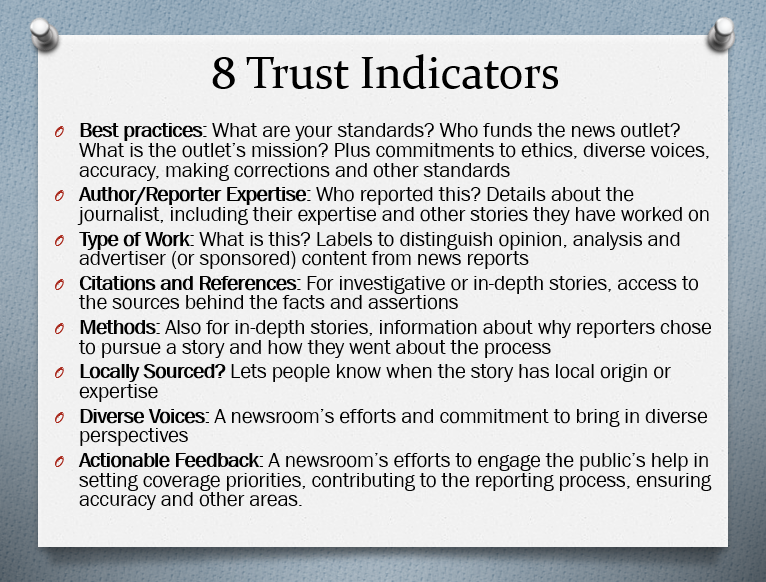

Transparency Standards by The Trust Project

Started in 2015, the Trust Project is an international consortium of more than 75 news organizations collaborating to restore the trusted role of the press in civic life. It has recently released “8 Trust Indicators” to help readers identify reliable news sources.

How Media Can (Re)Gain and Increase Audience Trust

The Coral Project’s Community Guides and Tools for journalists

The Coral Project was founded as a collaboration between Mozilla, The New York Times and The Washington Post. The guides designed are aimed to help people who work in journalism improve their strategy, skills and understanding for effective community engagement.

Their two open-source tools are built to help newsrooms engage more effectively to bridge the gap:

- Ask is a form/gallery builder to collect, manage and display user-generated contributions.

- Talk is a highly flexible discussion platform, designed for better dialog.

Krautreporter in Germany

Krautreporter is a digital journalism outlet founded in 2014 in Berlin by 25 journalists following a successful crowdfunding campaign. It is a nonprofit cooperative-based organization which does not publish advertising, relies on revenue mostly from subscribers, and has a porous “pay wall.” Its editorial/business model is innovative, as its members/users have a say in the stories, and journalists often count on their users’ geographical or thematic expertise when reporting. The mission of Krautreporter is trust. It wants to experiment with how media can be more trustworthy for citizens today.

GroundUp in South Africa

GroundUp is a niche news platform publishing mostly on health, education and human rights issues in relation to South African townships, which are often neglected by mainstream media. Started in April 2012 as a joint project of the Community Media Trust and the University of Cape Town’s Center for Social Science Research, it has developed into a community-centered news agency. Today, all GroundUp pieces are original stories of high daily relevance to its readers – with popular pieces including, for example, tip sheets on how to apply for social grants and housing – and made available for republication, usually under a Creative Commons license, to other media outlets.

This piece originally appeared on the Medium site of the Open Society Foundation’s Program on Independent Journalism and is reprinted with permission. Note: OSF is a funder of GIJN.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine.