Taking it to the Streets: Chequeado set up giant board games in five Argentine cities to spread word about their investigations. Credit: Chequeado’s Facebook Page

It was a sunny day in May when members of the Chequeado team carefully laid out a large board game in Plaza Moreno in La Plata, Argentina. The whole scene had an air of whimsy: dice that required two hands to hold, icons that stood four feet tall and circus performers that called passersby to try their hand at the fact-checking site’s version of “La Oca,” or the Game of the Goose.

But there was something important going on, beneath all the fun and games. The board told the story of the progress — or lack thereof — of public works in the city three years after a historic flood. The findings were a result of investigations by Chequeado, alongside local media outlets, journalists and a hackathon that counted on the participation of neighbors, engineers, programmers and high school students.

During that month, the same process was repeated in the plazas of four other cities around the country, focusing on local issues. The results of the investigation were also published in local publications.

The project, produced with support from the United Nations Fund for Democracy, was one of the online site’s biggest so far, according to Chequeado project coordinator Olivia Sohr.

Now in its seventh year, the site, says Sohr, is “always trying to think of new ways to present information so that it is more accessible and reaches the whole world.”

This kind of innovative presentation and rigorous investigation is what has made Chequeado a leader in data verification in the region — and around the world.

“Chequeado is a remarkable organization,” Alexios Mantzarlis, director of the International Fact-Checking Network, told the Knight Center. “They were among the first digital fact-checking projects and can now be considered one of the global leaders. They have continuously innovated their formats, channels and approaches in order to seek the greatest possible impact for the benefit of their cause: increasing accuracy in the public sphere.”

Launched in October 2010, the journalistic gamble has been rapidly gaining prominence and now counts 15 media partners from different Latin American countries among its ranks.

Founding Fathers

The history of Chequeado is unique. That’s because its founders do not fit the profile expected for this kind of journalistic project: they were not journalists, didn’t come from the world of politics and did not have experience in the nonprofit sector.

They were three professionals –a physicist, Julio Aranovich; an economist, José Alberto Bekinschtein; and a chemist, Roberto Lugo. All were veterans in their fields who had studied and lived for years outside of Argentina, and all were over 60 and either about to retire or already there.

But, as Chequeado’s director Laura Zommer explains, they “were consumers with a need not satisfied by traditional media; informed citizens who identified a deficiency.”

Sohr was Chequeado’s first employee and is currently the site’s project director. She told the Knight Center that Aranovich lived in the US for a long time, which is where he learned about FactCheck.org.

When he returned to Argentina, he thought that an initiative like that could work well in his country at a time – the year was 2009 and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was president – when the political and communication environment was extremely strained.

“According to what they read in Argentina (and what they read outside the country),” said Zommer, “they were told about two very different Argentinas.” And that was not acceptable for professionals who came from the scientific world.

Sohr, who studied sociology, was attracted to the start up for the challenge as well as the “idea of helping build a richer public debate” based on verifiable data and not just uncontested opinions.

“The spirit of Chequeado,” Sohr says, “is that if we want a citizenship that participates actively in democracy, we need for them to be informed with basic data to be able to arm their opinions.”

Team Chequeado.

Sohr and Matías Di Santi – who is now the newsroom coordinator – created a closed blog in November 2009 “where we started to try out the first articles, to see how the tone came across, to show it to friends, to see whether it worked,” Sohr explains. Almost a year later, in October 2010, Chequeado was officially launched with a team of five people.

A year and a half after later, they hired Zommer, a journalist and lawyer who had been teaching for two decades at the University of Buenos Aires on the right to information, with a focus on access to information and open data. At 22, she began her career at La Nación, where she covered judicial issues, civil rights, corruption and transparency in politics, among other topics. After a temporary stint as chief of staff at the Ministry of Internal Security, she returned to La Nación and also started working as communications director at Argentine think tank CIPPEC. It was there that she learned about Chequeado and fell in love with the project.

Joining the team had its economic risks, but Zommer says that she accepted the challenge because “I was quite convinced that I wanted to return to journalism and none of the Argentine journalism spaces had the freedom that I expected to work with.”

Since joining , Zommer has been in charge of executive management combined with coordinating the group’s journalism, hoping to be able to focus one day exclusively on the journalism. Her first goals: make Chequeado independent from its founders, increase its impact and create a more professional organization.

Going Pro

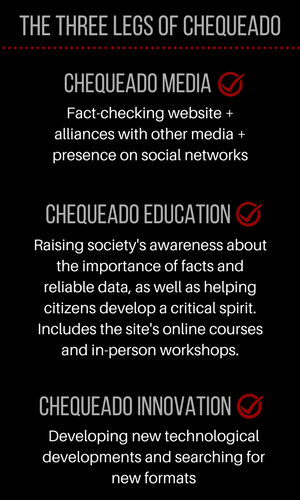

Transforming Chequeado meant establishing a rigorous approach to its methods along with the ability to share them with users and other sites interested in data verification. It also involved better defining the type of checks to be carried out, improving the presentation formats and growing the team with skilled professionals.

The site started out with two very young journalists with little professional experience. As Sohr explains, “it was very hard to go out and say that what the president says is false.” So, from the beginning, to gain credibility, they applied great transparency to their work, developing a method that, when Zommer arrived, was put in writing and published on the site for everyone to see.

“The method at Chequeado,” Sohr added, “helped us to better organize what were already doing. If we followed all the steps, it would be difficult to make a big mistake. ”

Now that fact-checking method has been shared with sites around the world. It is also used by Chequeado at checkathons and by its teams of volunteers – students in communications, economics, law or political science, who are trained by Chequeado to help with investigations.

The current Chequeado team consists of 16, mostly young, professionals. Three people are over 30, but the rest are under 30 and Chequeado has been their first job in many cases.

Checks, daily articles or explanations are the central part of the site’s work. As explained on the site, “we check the statements of politicians, economists, businessmen, public figures media and other opinion-forming institutions, and classify them as ‘true’ to ‘false’ according to how consistent they are with the facts and data to which they refer.” Chequeado also works with outside journalists for certain projects.

“Whether it is through their GIFS, their wildly successful educational programs, or their live debate visualizations, Chequeado always has the user (the informed citizen) in mind,” said Mantzarlis, of the IFCN. “Besides that, they have been generous in supporting new fact-checking projects across Latin America.”

Investing in Innovation

Pablo M. Fernández started working in media in 2002 at 20 years old, covering technology issues. After serving in leadership roles at magazines Information Technology and Apertura, working as homepage manager at La Nación and completing a brief stint at venture ElMeme, Fernández joined Chequeado in 2015, first as coordinator of innovation, moving up to director a year later. He is, in practice, the number two of the Chequeado team.

On the Bot: Chequeabot

One of the innovation team’s main challenges is to “think in terms of new formats” to present the information and reach a wider audience while maintaining journalistic quality. The team also develops technological tools to make Chequeado content more attractive.

One of the most innovative fields which the team is working with is artificial intelligence and the use of algorithms to automate tasks.

“We are creating an automated checking system that will help us to check faster,” Fernández explained. “It is our own development with open tools. It’s called Chequeabot.”

Each day this tool locates checkable phrases from about 30 media outlets and presents them at a weekly newsroom meeting, “as if it were a journalist,” Fernández said. In this way, the Chequeado team can review more media sites, especially from areas of Argentina that were not previously covered. Chequeabot produces a ranking of the phrases that it considers most testable. “Generally speaking, it is correct,” Fernández said, “but it also has an automatic learning component” since the editorial team can indicate whether it was right or wrong.

The technology that the Chequeado innovation team is developing also allows it to gain speed.

“The robot,” Fernández explains, “lets us know when it finds a similar phrase that we already checked. In real time. That is a great plus.” Thus, the team can react with great speed and “that generates a lot of visits, a lot of engagement.”

“The content generators are always going to be faster than us because it is easier to invent than to inform,” Zommer says. “Just as they use technology for viralization, we have to be able to use artificial intelligence in all the checking processes where we can do without humans.” Fernández adds that this “will allow humans to focus on the part of explaining and putting the data in context; things that artificial intelligence still doesn’t do better than us.”

Another function of the Chequeado bot, which is still in development, is to provide the best possible data on a current topic. For example, if the president of the country talks about poverty, the robot can present the journalist the best data available on that subject.

The team is very clear that this robot will be an important aid, but will never have the last word. That will always belong to the editorial team.

Fernández stressed that currently “nothing is being done in Spanish in this regard, and we believe that it can be something that other newsrooms can replicate.” In English, this same project is being developed by the British media outlet Full Fact.

Independent of the technological work based on algorithms, perhaps the clearest – or at least the most daring– example of innovations in format has been the presentation of results in the form of animated GIFs. This was a project made in collaboration with Argentine media outlet UNO, which is primarily aimed at millennials and is geared toward mobile phones and social networks. Zommer explains that “readership of the original articles that have GIFs increases because they circulate more.”

Fernández explained that “it was quite revolutionary for Chequeado because we had been working in a very rigid manner.” The practice of presenting a summary of the checks through animated illustrations “worked great,” he said. It also worked because “a lot of people read us on social networks,” and for a non-profit media outlet like Chequeado “it is very important to reach people through networks, even if they stay there.”

Down to Business

Chequeado is part of La Voz Pública Foundation, an NGO set up for verification of public discourse. The diversification of income channels is one of the keys to its business model.

The site has four main sources of income. The most important is international grants, which in 2017 represented 59 percent of total revenue. According to Zommer, each year Chequeado counts on between nine and 13 grants or institutional donations including the Omidyar Network and Open Society Foundations, though they have also received aid from the embassies of New Zealand, Canada, the Netherlands, Great Britain and the USs.

The second source is from companies; 17 percent in 2017. As a strategic decision, Chequeado does not offer advertising on its pages. The help of companies comes through events such as “La Noche de Chequeado,” the site’s main fundraising event held annually on the Monday before Journalist’s Day (June 7). Companies pay to be present in order to expand brand recognition among journalists, academics and social leaders in attendance. Participation has increased every year, with around 350 journalists attending in 2017. There are also companies that support particular projects of the Chequeado Education or Innovation programs. Chequeado’s other revenue-generating activities are the third source of income, at 14 percent in 2017.

Zommer believes that nonprofit organizations must “be able to monetize the social capital they generate.” In its case, they receive income for the publication of Chequeado content which appears in other publications or for online courses.

Finally, individual donations represent 10 percent of total income. They range from US $5 per month to US $10,000 per year, the latter of which is donated by the founder and CEO of e-commerce websites Mercado Libre, Marcos Galperin. Currently, there are about 400 individual donors and the number increases year after year.

The site receives approximately 300,000 monthly visits, but according to Zommer, its “audience exceeds one million people” when all the platforms and media in which its content is present are taken into account. “And surely,” she adds, “among that million are all the politicians, academics and relevant journalists” of Argentina.

In terms of audience, the main jump took place during the first presidential debate in Argentina in 2015. “Traffic grew 700 percent that year, and then our challenge was not to lose it,” Zommer said.

Despite this growth, one of the great – and most difficult – challenges faced by the Chequeado team is to measure impact. It is not simply about knowing how many clicks a given story achieves, how a topic circulates through social networks or how many times a particular work is cited in other media. These are important, but those responsible for the project want to go much further to “work on the things that really have the most impact” on society, as Sohr explained.

It’s a project the team is constantly working on. They conduct surveys and focus groups with the audience and also participate in the International Fact-Checking Network –Chequeado is part of its steering committee – where common tools are developed that can be used by organizations that are part of the network “to make it cheaper for all and also to be able to later compare the impact achieved with these tools in different places.”

Taking stock of the first seven years of the site, Zommer reflects on Chequeado’s achievements. They’ve developed a financial model that allows quality journalism, they’ve established a brand associated with trust, and they’ve created a self-demanding team that works to hold people accountable. But she still sees room for improvement. They need to figure out how to better disseminate their research and to take a closer look at what Chequeado produces, not moving so quickly to the next project.

The excitement that’s felt among the Chequeado team regarding the possibilities offered by data verification, along with its permanent commitment to innovation, foretell a bright future for this project. Don’t take our word for it. Check it out for yourself.

This is an edited version of a story which first appeared on the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas blog as part of a special project on Innovators in Latin American and Caribbean Journalism. The Innovators in Journalism series is supported by the Open Society Foundations (also a funder of GIJN) and covers digital news media trends and best practices in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Ismael Nafría is a journalist, consultant, professor and lecturer who specializes in digital media. He is also the author of La reinvención de The New York Times (The Reinvention of The New York Times).

Ismael Nafría is a journalist, consultant, professor and lecturer who specializes in digital media. He is also the author of La reinvención de The New York Times (The Reinvention of The New York Times).