Tunisia is often cited as the most liberal country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and the only country which has truly benefited from the regional uprisings in 2011.

Tunisia is often cited as the most liberal country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and the only country which has truly benefited from the regional uprisings in 2011.

“In Tunisia, I think we can have higher expectations than just that the police don’t arrest people for being activists,” says 42-year old Malek Khadhraoui, the publishing director of the Tunisian online publication Inkyfada.”This is behind us, okay, but we still (have) a lot of other problems. Corruption is killing the state, we have a big economic crisis and there is a problem of management and the distribution of resources.”

Since 2014, the publication has focused on investigative journalism supported by visual storytelling and interactive reading experiences.

Not long ago, Inkyfada published a piece on uneven development policy in Tunisia, focusing on the fact that big cities and coastal regions have been prioritized over the rural parts of the country. Using Kasserine, one of Tunisia’s poorest regions, as an example, reporters discovered that for the past five years, 80 percent of the money set aside for development in the region had not been spent.

“It was not only a question of money because the state did not even succeed in implementing things for which they already had the money,” Khadhraoui says. “It was a question of inefficiency, corruption and mismanagement. Our story explained to the people of Kasserine why their situation is so bad. And this gets at the heart of what we want to do — give more insight into complex issues and go beyond the superficial explanation. We want to counterbalance the voice of the mainstream media who just broadcast the official (government) version without any contextualization, without any critical questions.”

The DNA of Inkyfada

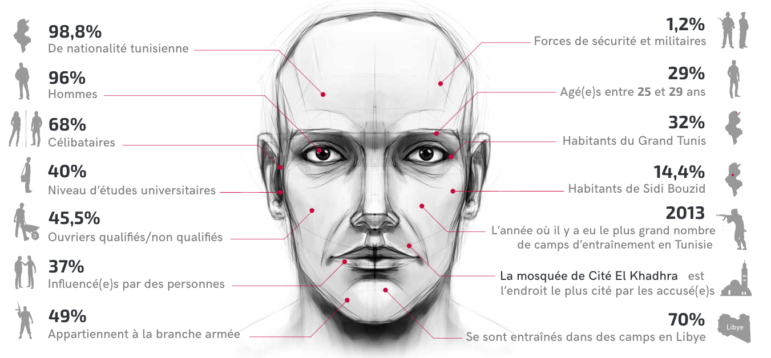

Portrait of a Terrorist? One of the visuals developed for Inkyfada’s story on presumed Tunisian terrorists.

With a focus on visual storytelling and interactive experience, the team often spends weeks developing special designs to accompany and help tell the stories.

“This is the DNA of Inkyfada,” Khadhraoui says. “It works just like a media lab with journalists, developers and graphic designers.”

An example of this approach is their story on presumed Tunisian terrorists, a visualization which provides interesting information of people on trial for acts of terrorism, moving past the usual stereotypes.

“This is a quite typical story for Inkyfada,” says Khadhraoui. “A lot of visuals based on a lot of data; 1000 judiciary cases. The story had a significant impact both in Tunisia and abroad, especially for people working on the terrorism issue.”

Drawing the Line

Aside from their journalistic approach — which alone makes Inkyfada quite unique in the Tunisian context — their structure also sets them apart.

Inkyfada is part of an NGO, a structure designed to protect their independence and their journalism. Called Al Khatt — which means “the line” in Arabic and refers to the editorial line of Inkyfada — the NGO was started in 2013 by Khadhraoui and seven others who all used to work with the influential Tunisian blog collective Nawaat.

“The idea from the beginning was to create a (publication), but also to protect it from any interference in editorial content, which can happen if you receive grants,” says Khadhraoui, who is currently the president of the NGO, though a new president will be elected in the spring. “So, we created Al Khatt as a structure which ensures the arm’s length principle between Inkyfada and the donors.”

Besides Inkyfada, Al Khatt has two other dimensions: An advocacy arm which promotes press freedom and a web engineering laboratory that provides technical innovation and solutions for both Inkyfada and advocacy arm of the group.

Going Long, and Deep

The editorial team has recently grown and now includes a staff of 11, something which has allowed the team to quadruple their journalistic production from two to eight pieces a month — two of which will be longform stories.

Because Inkyfada does not publish daily, their stories often have a longer shelf life than other more time-bound news articles. For example, the very first story published on the site — an interactive timeline of attacks and activities related to terrorism in Tunisia — continues to be relevant and in use.

Terror timeline: Inkyfada’s first data-heavy interactive on terrorism in Tunisia continues to be relevant.

“This kind of content creates a long-term relationship with readers and generates regular traffic on the website,” says Khadhraoui. “The map has become very valuable for researchers, other journalists and people who write about Tunisia.”

The stories are published in both Arabic and French and, though the vast majority of readers are from Tunisia and France, the site regularly receives traffic from US, Canada and the rest of the MENA region. Every month, between 70,000 to 100,000 visitors visit the site. But big stories – such as Panama Papers, Swiss Leaks or in-depth investigations on Tunisia – see the number explode, and can reach up to 1 million.

Working for the Future

Though conditions for media and for civil society organizations have improved since the years of former President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, it is still too early to call it a day.

“I do not want to paint a dark picture of the situation but at the same time, I’m not being completely optimistic by just saying: ‘Yeah, we are a democracy now and everything is fine.’ It is still about fighting for what we have achieved and not going back.”

One issue Inkyfada is dealing with constantly is access to information.

Though the right to information is granted through the constitution, it remains difficult either because the state simply withholds certain information, or because civil servants have not been informed on how to reply to such a request. No official explanation exists on how to provide the data, where to find it and in what format it should be delivered.

As a response to this tiresome struggle, Inkyfada has chosen a consistent response. Every time an administration refuses to give them information, Inkyfada sues it.

“It is work for the future – in two years we will have a lot of decisions proving that it is our right to access information. It is a matter of holding the state accountable,” Khadhraoui says.

But struggling with an administration not yet geared to serve its citizens in the new post-revolution reality is one thing. Fighting the bleak forces who want to downright repeal the advances in Tunisian society is another.

A recent leak from a whistle blower showed that certain powers in Parliament want to re-evaluate and limit the association law, which was changed in 2011 to protect NGOs and acknowledges their role in society.

Though Khadhraoui sees this as a negative development, he is still confident that civil society has gained enough power and has enough support in Parliament to efficiently fight back.

International Media Support (IMS) partners with Al Khatt through the Danish-Arab Partnership Programme and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and is currently working with them on podcasts. Inkyfada is one of seven digital frontrunners supported by IMS in the MENA region.

This post first appeared on the International Media Support website and is reproduced here with permission.

Gerd Kieffer is a communications and press officer at International Media Support. She was previously a freelance writer, whose work appeared in Berlingske, Udvikling, Politiken and Bouffe Media.

Gerd Kieffer is a communications and press officer at International Media Support. She was previously a freelance writer, whose work appeared in Berlingske, Udvikling, Politiken and Bouffe Media.