In a favorite old Doonesbury cartoon, reporter Rick Redfern is having a birthday. His girlfriend Joanie Caucus presents him a special surprise — a secret document!

But serendipitous leaks wrapped with paper and ribbon are rare. Most information is hard earned. Still, if good luck is earned, it never hurts to ask. And asking is getting easier and more sophisticated.

Boring old boilerplate appeals for help are being made more inviting. Communication channels are being fortified to protect informants.

Creative use of social media provides new ways for journalists not just to solicit tips, but also to tap readers’ expertise, opinions and personal experiences.

A stronger ethos of reader engagement is resulting in more sophisticated appeals from journalists for assistance with investigations, including:

- Seeking tips on very defined topics

- Asking readers to talk about their experiences on broad subjects

- Inviting comments after publication

Here are examples of what your colleagues are doing:

Hey, Shell Employees!

Dutch reporter Jelmer Mommers of Dutch news site De Correspondent appealed directly to Shell employees for information in a lengthy blog post, as described in this article. The resulting investigation revealed that Shell had detailed knowledge of the dangers of climate change more than a quarter century ago.

Dutch reporter Jelmer Mommers of Dutch news site De Correspondent appealed directly to Shell employees for information in a lengthy blog post, as described in this article. The resulting investigation revealed that Shell had detailed knowledge of the dangers of climate change more than a quarter century ago.

Along the way, in what Jelmer calls “the most romantic moment,” came the surprise delivery of a box full of internal documents. De Correspondent’s emphasis on communicating with subscribers is described here.

Call for Childbirth Experiences

Getting reader input in advance was key to a major U.S. story on maternal health to which thousands of people contributed. ProPublica engagement reporter Adriana Gallardo and her colleagues published a questionnaire in February of 2017 aimed at women who had experienced life-threatening complications in childbirth.

Using a variety of social media channels, Gallardo, along with ProPublica’s Nina Martin and NPR’s Renee Montagne, received several thousand responses. The personal stories fueled a series and the connections made are still being maintained for follow-up work. Read more in this this GIJN article.

Using a variety of social media channels, Gallardo, along with ProPublica’s Nina Martin and NPR’s Renee Montagne, received several thousand responses. The personal stories fueled a series and the connections made are still being maintained for follow-up work. Read more in this this GIJN article.

Testimonials from Mexico’s Drug War

“Anyone’s Child Mexico” is a documentary about the families affected by Mexico’s drug war. To gather stories, the producers of the documentary publicized a free phone line through local partners and asked people across Mexico to call in and recount their stories.

“Anyone’s Child Mexico” is a documentary about the families affected by Mexico’s drug war. To gather stories, the producers of the documentary publicized a free phone line through local partners and asked people across Mexico to call in and recount their stories.

Callers could also listen to other testimonials. With funding from the University of Bristol’s Brigstow Institute, producers Matthew Brown, Ewan Cass-Kavanagh, Mary Ryder and Jane Slater created a website to bring together audio, photos, video and text and tell harrowing stories of a country ravaged by violence.

Using Social Media While Traveling

Johnny Harris, a video reporter at Vox, has been exploring the impact that borders have on people living on either side of them. He asked for suggestions via social media on where to go for the series, netting 6,000 replies from around the world. While traveling in six countries he inquired about what to see and do. “The fact that we can use the internet to have real-time interaction with the audience is, to me as a reporter, the pinnacle of the use of this medium,” Harris told Journalism.co.uk.

Johnny Harris, a video reporter at Vox, has been exploring the impact that borders have on people living on either side of them. He asked for suggestions via social media on where to go for the series, netting 6,000 replies from around the world. While traveling in six countries he inquired about what to see and do. “The fact that we can use the internet to have real-time interaction with the audience is, to me as a reporter, the pinnacle of the use of this medium,” Harris told Journalism.co.uk.

After Publication: Tell Us More

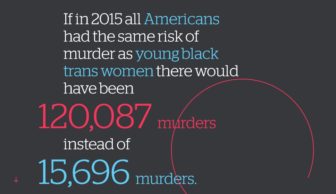

Creating a database on transgender murders in the United States was a difficult challenge successfully met for a prize-winning story, “Unerased: Counting Transgender Lives.”

Creating a database on transgender murders in the United States was a difficult challenge successfully met for a prize-winning story, “Unerased: Counting Transgender Lives.”

Written by Meredith Talusan, with Mathew Rodriguez, Anna Swartz, Brianna Provenzano and Marie Solis, the story won the Al Neuharth Award for Innovation in Investigative Journalism sponsored by the NLGJA — The Association of LGBTQ Journalists. Looking to continue their work, the opening page of their story has a “Submit a tip” link to a page that invites readers to “tell us about an instance of transgender violence we’re missing, or use this form to give us tips on other stories we should cover.”

Lessons from Crowdsourcers

Reaching back further, to 2015, ProPublica and The Virginian Pilot crowdsourced 3,352 stories from persons exposed to Agent Orange and wrote about the experience. The Five Things We Learned Collecting 3,352 Stories About Agent Orange Exposure boiled down to:

Reaching back further, to 2015, ProPublica and The Virginian Pilot crowdsourced 3,352 stories from persons exposed to Agent Orange and wrote about the experience. The Five Things We Learned Collecting 3,352 Stories About Agent Orange Exposure boiled down to:

- Holy crap, email!

- The right community isn’t always the largest.

- If you’re not listening, you’re doing it wrong.

- Iterate with your community.

- Have a plan for finding stories.

Questions at the Bottom

Yet another recent technique, used by The Guardian, involves asking questions at the end of articles. Readers are invited to vote for topics they want more detail on. The data from the tool, called Reader Questions, is fed back to editors to shape future coverage.

Term Just Decade Old

The term crowdsourcing originated in a 2006 article by Wired writer Jeff Howe and the technique has been employed with multiple variations.

“The research shows that crowdsourcing is credited with helping to create amazing acts of journalism,” according to the 2015 Guide to Crowdsourcing by Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

“The research shows that crowdsourcing is credited with helping to create amazing acts of journalism,” according to the 2015 Guide to Crowdsourcing by Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

Notable crowdsourcing history was made in 2007 when Josh Marshall and Paul Kiel of TalkingPointsMemo.com late one night asked readers “to Comb Through Thousands of Pages.” The research helped them report on the politically motivated dismissals of eight Justice Department attorneys.

In 2009, The Guardian asked the public for help to analyze 700,000 pages of documents about the expenses of members of the British Parliament.

The Tow Center researchers said that real crowdsourcing involves a call for specific information, not just an open invitation to readers. “A structured call-out” means asking people to respond to a specific request. (GIJN wrote about its use in investigative journalism in a 2010 article by Nils Mulvad.)

Over a 21st Century Transom

Open invitations to readers for tips aren’t new, of course, but they have been getting a makeover. Some are very short, like this one from Huffington Post:

Give Us the Scoop

Give Us the Scoop

Do you have a news tip, firsthand account, information or photos about a news story to pass along to our editors? Send a news tip or email us at scoop@huffingtonpost.com

Others get into more persuasive detail, such as this one from the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia:

GIVE US A STORY IDEA

Here you can submit a story proposal to CINS reporters. The story can be about any of the issues that CINS usually covers: corruption, organized crime, rule of law, politics and transparency and accountability of politicians, energy and environment, education, health, sports or another issue you think that can be of interest to the public.

Here you can submit a story proposal to CINS reporters. The story can be about any of the issues that CINS usually covers: corruption, organized crime, rule of law, politics and transparency and accountability of politicians, energy and environment, education, health, sports or another issue you think that can be of interest to the public.

You can submit evidence and describe facts that make you think your proposal should be thoroughly investigated. The evidence may be documents in common electronic formats, photos or video/audio material. The information you provide will be examined only by the CINS editor-in-chief, which guarantees that sources will be protected. If you do not wish to submit your information on our website, simply send us an email address that we can use to contact you.

Providing Tipsters with Secure Options

Many media outlets have moved to provide greater security for informants.

The New York Times says:

Do you have the next big story? Want to share it with The New York Times? We offer several ways to get in touch with and provide materials to our journalists.

The paper goes into further detail:

What Makes a Good Tip?

A strong news tip will have several components. Documentation or evidence is essential. Speculating or having a hunch does not rise to the level of a tip. A good news tip should articulate a clear and understandable issue or problem with real-world consequences. Be specific. Finally, a news tip should be newsworthy. While we agree it is unfair that your neighbor is stealing cable, we would not write a story about it.

A strong news tip will have several components. Documentation or evidence is essential. Speculating or having a hunch does not rise to the level of a tip. A good news tip should articulate a clear and understandable issue or problem with real-world consequences. Be specific. Finally, a news tip should be newsworthy. While we agree it is unfair that your neighbor is stealing cable, we would not write a story about it.

For sending in tips, the Times discusses using WhatsApp, Signal, email, postal mail and SecureDrop.

SecureDrop is an open-source whistleblower submission system that media organizations can use to securely accept documents from and communicate with anonymous sources. It was originally created by the late internet activist Aaron Swartz and is currently managed by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

AmaBhungane, South Africa’s nonprofit center for investigative journalism, invites tip offs, provides protected methods, and warns “you also need to be aware of the risks, and take steps to protect yourself.” The group’s slogan, “Digging dung, fertilizing democracy” (amaBhungane is the Zulu word for dung beetle), renders the risks in detail and offers advice. About delivering hard copy documents, for example, it cautions, “Protect yourself: Do not identify yourself on the package or in the documents; get someone who you trust but who is not obviously linked to you to deliver the document.”

AmaBhungane, South Africa’s nonprofit center for investigative journalism, invites tip offs, provides protected methods, and warns “you also need to be aware of the risks, and take steps to protect yourself.” The group’s slogan, “Digging dung, fertilizing democracy” (amaBhungane is the Zulu word for dung beetle), renders the risks in detail and offers advice. About delivering hard copy documents, for example, it cautions, “Protect yourself: Do not identify yourself on the package or in the documents; get someone who you trust but who is not obviously linked to you to deliver the document.”

The Washington Post “offers several ways to securely send information and documents to Post journalists.” It says:

No system is 100% secure, but these tools attempt to create a more secure environment than that provided by normal communication channels. Please review the fine print before using any of these tools so you can choose the best option for your communication needs.

No system is 100% secure, but these tools attempt to create a more secure environment than that provided by normal communication channels. Please review the fine print before using any of these tools so you can choose the best option for your communication needs.

Options include Signal, Peerio, WhatsApp, Pidgin, encrypted email, SecureDrop and postal mail.

For an even broader overview, read a compilation of U.S. media solicitation techniques written by Gloria Shur Bilchik in Occasional Planet.

Also see a comparison of different options by Martin Shelton in The Source, entitled Opening Secure Channels.

Byline Invitations

Bylines are sometimes accompanied by invitations for reader input.

An extra level of security is provided by giving a PGP fingerprint. Here’s an example:

J. Lester Feder is a world correspondent for BuzzFeed News and is based in Washington, DC. His secure PGP fingerprint is 2353 DB68 8AA6 92BD 67B8 94DF 37D8 0A6F D70B 7211

J. Lester Feder is a world correspondent for BuzzFeed News and is based in Washington, DC. His secure PGP fingerprint is 2353 DB68 8AA6 92BD 67B8 94DF 37D8 0A6F D70B 7211

Contact J. Lester Feder at lester.feder@buzzfeed.com.

PGP stands for Pretty Good Privacy. The tool allows users to both encrypt and decrypt emails. Here’s a tutorial on PGP, an article by Jacob Hoffman on why reporters should use it, a Poynter Institute article and a Gawker article.

For another example, see Foreign Policy’s tips invitation.

Community Outreach

A collection of many kinds of outreach efforts, often involving community meetings, was published in April by the Institute for Nonprofit News and Dot Connector Studio.

One 2016 example cited a project by the Center for Michigan and Bridge magazine, which was led by an engagement team. More than 5,000 state residents participated in face-to-face discussions and phone polls for the project, “Fractured Trust: Lost Faith in State Government, and How to Restore It.” Bridge credits this type of engagement for countless story ideas from communities across the state, and the Center says they have reached more than 40,000 people, and “provided public momentum for policy change aligned with citizen views.”

One 2016 example cited a project by the Center for Michigan and Bridge magazine, which was led by an engagement team. More than 5,000 state residents participated in face-to-face discussions and phone polls for the project, “Fractured Trust: Lost Faith in State Government, and How to Restore It.” Bridge credits this type of engagement for countless story ideas from communities across the state, and the Center says they have reached more than 40,000 people, and “provided public momentum for policy change aligned with citizen views.”

The benefits of such “audience engagement” campaigns are extolled in a 2015 article by Jack Murtha in the Columbia Journalism Review. Murtha notes the example of Canadian reporter Brielle Morgan from the investigative reporting website Discourse who teamed with a unit of Canada’s National Film Board to set up public “Listening Events” on the topic of the child welfare system. An article in Images & Voices of Hope by Mike Wallberg describes the effort and the results.

Internews unveiled the The Listening Post Collective and a seven-step playbook “to help journalists engage with their communities,” and a toolbox for journalists, including a guide to setting up an SMS messaging system, information about setting up community recording devices and a guide to crafting questions.

Internews unveiled the The Listening Post Collective and a seven-step playbook “to help journalists engage with their communities,” and a toolbox for journalists, including a guide to setting up an SMS messaging system, information about setting up community recording devices and a guide to crafting questions.

The Coral Project is a comprehensive site on community involvement, covering the ins and outs of public comments, and offering open source software to journalists and newsrooms to facilitate community interaction.

A variety of crowdsourcing ideas were summarized in an article by Mădălina Ciobanu for Journalism.co.uk. Examples included the use of a Google form that asked people structured questions about their reasons for migrating. She also drew attention to Groundsource, which provides a unique phone number to collect text messages and is being used by media organizations and others to gather information from their communities.

In the spirit of this topic, please send us more examples. Write us here.

Toby McIntosh is director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He was editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), writing about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.

Toby McIntosh is director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He was editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), writing about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.