Opening Up: Anastasia Valeeva (right) at a data journalism course at the American University of Central Asia.

Anastasia Valeeva, a Russian-born investigative journalist who specializes in open data, has been exploring the state of data journalism in her home country. For a paper at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, “Open Data in a Closed Political System: Investigative Open Data Journalism in Russia,” Valeeva interviewed 13 journalists and open data researchers from Russia and the UK, and analyzed 30 data investigations on topics ranging from corruption in procurement to the Panama Papers.

Valeeva began her career at Russia’s NTV television network, and later became an international producer working on exclusive reports, including stories from North Korea and a documentary on transgender people in Russia. In 2012, Valeeva left Russia to get her second masters and then taught herself skills to become a data journalist.

She spoke with GIJN’s Russian editor Olga Simanovych about the state of data journalism in Russia and beyond, why she got into the field and what she learned on her recent research project.

Most journalists consider working with numbers a tedious, difficult and thankless task. Why did this work become so attractive for you?

Data journalism was my personal exit from a professional crisis in 2012, when I left NTV and the country. I was disillusioned about the process of getting information, where you get “exclusive” information from the same newsmakers. I became incredibly tired of interviews and newsmakers, where the explanations were done by experts, where you interview a person already knowing what you want him to say. For me, data journalism is just a good, smart journalism.

What has changed in data journalism since you started working in the field?

I am definitely not an expert — at most I’m a specialist. I can see data journalism is changing fast, especially in the U.S. The New York Times is already doing less interactives based on the lessons learned, whereas we here have not even started. In Europe the so-called “hype” is over, and in some publications, such as Die Zeit or The Guardian, data journalists are part and parcel of the newsroom. It is interesting to see things evolving in Russia; it’s at the very beginning.

State of Data: Google News Lab Report

Research into the field is vital if we want to move further. The Google News Lab recently published “The State of Data Journalism in 2017.” The only problem I have with their methodology is the choice of countries: the U.S., UK, Germany and France. I don’t think we can have a real talk about the democratizing effect of open data, let alone the in-depth quality of data-driven reporting, if we only look at those countries.

This was also a premise of my research hypothesis: I believe in open data as another information liberation engine, so I wanted to explore if the Russian government was releasing meaningful datasets and if journalists were skilled enough to scour it for scoops.

What major findings surprised you the most?

In some areas the Russian government does publish considerable amounts of open data, such as in the financial sector and especially in procurement. But sectors such as health, crime and education leave much to be desired, especially in terms of granularity and the standardization of data. The laws are in place, some of them since 2006, but much more needs to be done in terms of implementation.

In terms of investigative journalists as the end users of open data, I found that in many cases journalists still prefer the classic framework of getting the insight, keeping control over narrative and calculating things manually. They would not open up the storytelling part to the team, with a developer and a designer on board.

However, I’ve seen and analyzed these types of collaborations at data journalism hackathons which have become quite popular in Moscow and Saint Petersburg since 2016. The depth of data analysis and the added value of graphics to the stories that were produced at those hackathons is what I wish Russian newsrooms could replicate.

How do journalists in former Soviet Union countries manage to make the best of the data available?

Investigative journalists have been using data before it became trendy. Now, as the documents have grown in volume, they all have had to become data journalists in a way. I am talking here particularly about Novaya Gazeta, which worked with International Consortium of Investigative Journalists on the Panama Papers and with Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project on the Russian Laundromat series, and RBK which has built up a reputation for investigations based on in-depth work with procurement data.

Sourced: Screenshot from a Baba Zina data story.

When I was looking at the stories published at the end of the data journalism hackathons, I really admired work of the team Baba Zina, a regular participant of media hackathons. They have a professional data analyst on their team, and you can feel it since they always publish a source code and data alongside the story. That’s real open data journalism.

In other countries in the region, Texty is doing great job in data journalism in Ukraine, but also tut.by in Belarus or Vechernyi Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan produce decent stories with data. It’s just that they don’t really create entirely data-driven reporting; they report on statistics instead. They are just one step away from doing data journalism.

How much money are media houses ready to invest in data journalism?

It’s hard to say. But considering that there is no single publisher in Russia with a data team, you can see that editors are not ready to invest. But it is the same funding problem with classic investigative journalism. The potential of data journalism — it’s added value to the quality of the content — is not yet understood.

What prevents journalists in post-Soviet countries from doing more qualitative investigations based on data?

After a training in Montenegro last year, which had participants from Ukraine, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, I wrote a blog about hurdles and joys of introducing data journalism in post-Soviet countries. The problem is the structure of journalism education and the mass media system in those countries. As long as journalists think of themselves as writers in miniature, and as long as the salaries are paid depending on the number of articles and clicks, it’s hard to change things. But Ukraine is a great example of things changing and becoming possible.

What’s happening in Ukraine that makes it unique?

It’s just an observation, but it seems that with the new government, data journalism initiatives have the support needed for growth. Together with an open government agenda, it has prepared the ground for data journalism to flourish. Now they have newsrooms that understand and harness the value of data-driven stories, like Texty and organizations like Internews which do a lot of work on the ground; also the discipline is being taught in the universities.

What’s unique about what you teach in your classes in the former Soviet Union?

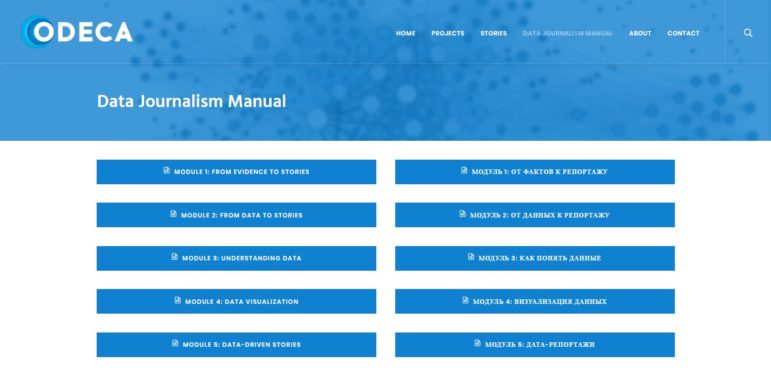

All the materials that we use for classes, are free and available online. The program was developed by Eva Constantaras, the data journalism advisor at Internews and international data journalism consultant; I have translated it and adapted it to the local context. The main focus is to teach critical thinking with data, so it begins with reading data stories, examining their lead into the data, discovering regional data portals and finally building one’s own hypothesis that’s then tested with data.

I don’t think there is something unique (about what I teach in the former Soviet Union countries) that is is not taught in the other (countries); it’s a lot of Excel, plus some scraping and visualization tools.

However, I’ve noticed that it is very important to localize the context of what you are teaching. Before every training we study the issues in the local media, the data available on the regional data portals and also adjust to the interests’ of the participants during the training itself. For example, in Europe I was working a lot with migration data, while in Kyrgyzstan we covered health issues extensively and in the Balkans participants were courageous enough to dive into topics such as drugs, domestic violence and water quality.

What common mistakes do people make working with data?

Passing it On: Valeeva (middle) training young European journalists.

The most common mistake, in my view, is blind faith in data. Every journalist uses numbers, but they rarely check where those numbers came from. When working with data, you have to be very careful interpreting it: you can’t mix up a poll with a demographic survey; you can’t confuse correlation and causation. It’s the same as when you choose the proper expert for your interview — your data should be a proper expert that can talk about the subject.

What changes do you expect for the future for data journalism?

On one end it would be highly personalized super-computer journalism, as Tim Berners-Lee describes it in his futuristic articles; when you open a website and it’s already adjusted for your profile, and you search for a dentist and get the best one according to every parameter, including your schedule. But I would love much more to see the other, more “ordinary” future: when all the journalists can analyze the numbers and talk to them as well as they talk to people.

What would you recommend to people who are just beginning to deal with data journalism?

To start your own first project right now.

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB and has participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English and Greek.

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB and has participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English and Greek.