Mexico is now near the end of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration. He recently started his fifth year as head of the federal government and public perception as well as political analysis show the balance is not in his favor.

Mexicans, and the world, are witnessing acts of corruption, crime and violence, as we had not seen in the past. However, in spite of how critical the national and foreign media has been regarding the administration of Peña Nieto, no legal action has been made and, in consequence, no legal sanctions have been issued.

Mexicans, and the world, are witnessing acts of corruption, crime and violence, as we had not seen in the past. However, in spite of how critical the national and foreign media has been regarding the administration of Peña Nieto, no legal action has been made and, in consequence, no legal sanctions have been issued.

Cases such as the purchase the President’s wife and Mexico’s first lady made of a $7 million mansion, acquired from the subsidiary of one of the favorite contractors of Peña’s government, clearly makes influence peddling evident both in Mexico and abroad and have remained in impunity. Cases that have been documented by investigative journalists, and well-organized civilian groups, which expose documents, interviews, analysis, expert reports, are constantly discarded by the authorities.

What the government of Peña Nieto has done in some states is officially and unofficially enforce pressure against these journalists and these citizens. The methods are diverse, including spying on them, ordering audits of their businesses, ignoring them, suing them or trying to slander them for their work.

Corruption, according to the Bank of Mexico, costs Mexicans anywhere between 8 and 9 percent of the gross domestic product, while the Institute of Geography and Statistics points out that in 2016, the cost of corruption for the business sector was 600 billion pesos (about $32 billion) — most of which is what businessmen paid to get through the government’s endless red tape.

This level of corruption, however, isn’t punished accordingly. The attorney general, the Ministry of Finance and the Comptroller’s Office of Mexico are seriously committed to satisfying the interests of the president and the members of the cabinet who belong to his party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party. Influence peddling and conflict of interest are constant practices in Peña Nieto’s government, and it seems impossible for citizens to investigate this in depth, while internationally there’s frustration as everyone sees how the country sinks deep into a hole of corruption.

The abuse of public power is an issue that dominated the early years of Peña Nieto’s government. Cases such as that of Ayotzinapa in September of 2014, when local security forces abducted and disappeared 43 students and killed six more, remain in impunity, due to the involvement of officials in the Attorney General’s office in handling the evidence in an effort to not resolve it.

The same thing happened in the case of Tanhuato in 2015, when in a confrontation with criminals the Federal Police riddled 42 of them with bullets. In both investigations low-level arrests were made, proving, on the one hand, that the federal administration is a repressive authority that uses armed forces, and on the other hand exposing the inability of the authorities to investigate, enforce the rule of law and bring the perpetrators to justice, even when they’re a part of their government structure.

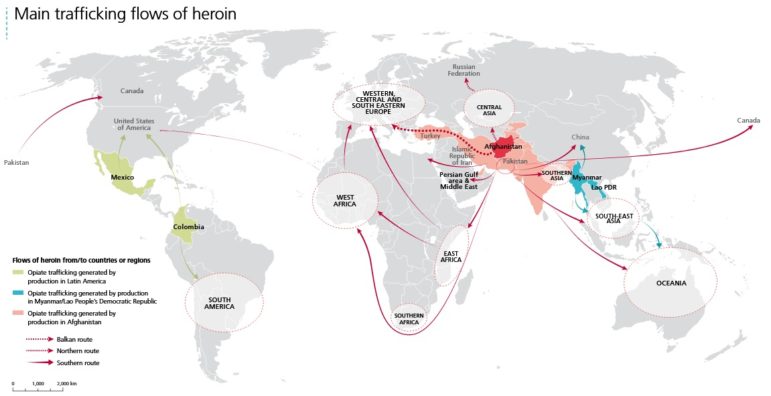

Drug trafficking has grown in Mexico in the last five years.

By corrupting the police force, and with the impunity that judicial and investigative structures provide due to either complicity or inefficiency, organized crime and drug trafficking networks have spread out in Mexico far and wide.

Under these conditions the country went from being a transit country for drugs heading to the United States to a nation that now freely and heavily consumes and distributes drugs, and this is what led us, over the past six years, to the so-called war on drugs.

The arrests of major drug lords in Mexico didn’t exterminate organized crime at all, but what it did manage to do was disperse the drug cartels. We now have fewer crime bosses and more low-key drug distributors who have turned street corners of Mexico into a war zone because that is where they sell drugs, causing a chaos of delinquency and unleashing a wave of violence.

Journalism Under Deadly Threat

How do journalists in this climate of violence, crime and corruption, report the news?

Many times journalists end up doing the work of the criminal investigation authorities, which makes them very vulnerable as they face dishonest public officials that have the full power of the state on their side, or criminals who, with impunity, control their turf with guns and bloodshed.

Journalists in Mexico are caught in the middle of two very dangerous forces: the bullets of drug traffickers and the pressure of the government.

In recent years, investigative journalism has focused on both: corruption and drug trafficking. Teams of investigative journalists in the independent media and social groups have been created to analyze official data to follow the path of the money and reveal the source of corruption, and to observe the networks of impunity and exhibit how authorities are colluding with criminals.

Regarding corruption, investigative journalism has shown how public officials use the federal budget to meet their personal needs, purchase aircraft, buy houses, overspend and even use it for their own entertainment.

A news portal, in collaboration with a social organization, published a robust piece of research to document how 11 ministries, eight universities and 186 companies had diverted over 7 billion pesos (about $377 million) from the federal budget in two years.

The investigation included official documents, proof of the international criminal network and how the money was diverted, including budgets, appropriations and the use of shell or bogus companies. Even though the story was published in the independent media, the attorney general failed to initiate an investigation, and the heads of the ministries involved or the university presidents didn’t do their share to at least clarify where they stood regarding how corruption is at the root of a situation in which over 7 billion pesos disappeared from public funds.

Faced with the evidence of corruption that investigative journalists produced, Mexicans have clearly witnessed a network of complicity from the governmental sphere, and the cover-up of each other’s acts of corruption.

Another story unveiled how construction giant Odebrecht bribed the director of Petróleos Mexicanos with over US$10 million in exchange for the allocation of public works. The investigation didn’t just consider official documents obtained from the Brazilian courts, and official information related to public works contracts, Brazilian business owners were also interviewed. They described the way in which they delivered money to public officials, not only revealing amounts and routes, but also providing bank accounts, financial institutions and dates of the transactions. All the evidence was provided in a clear and timely manner and was documented in an investigative journalism story that only resulted in the Attorney General’s Office issuing an order to distance themselves from these accusations.

Mexico is one of 12 countries where bribes of the Brazilian company, Odebrecht, took place and no arrests have been made in connection with this case of international corruption.

When it comes to drug traffickers, journalists constantly prove the impunity the traffickers enjoy, while investigating the routes they follow to transport drugs, launder money and gain control of a certain territory. We also investigate the trail of murders they leave behind, their names and their pictures. All these facts, in the hands of the investigating authority and, in some cases, the judiciary authorities as well, remain hidden, sheltered from researchers because of several factors: 1. Complicity, 2. Corruption, 3. Inefficiency in the Public Ministry, 4. The new system of criminal justice in Mexico.

About the complicity: in our weekly publication, Zeta, we have written for years about how criminal networks couldn’t survive without police protection. Through investigative journalism we have shown how the Federal Police work for some drug cartels while the local police do another cartel’s dirty work. As a result of this, police officers have been killed, detained and released, because they have favored a certain drug trafficking structure.

While investigating corruption, we have written stories demonstrating how agents and police officers have stolen drugs, received money in exchange for protection and are on the criminals’ payroll. As the first decade of the new millennium began it was explained how the Arellano Felix drug cartel spent a million dollars a month paying corrupt policemen, researchers and officials from the justice department precisely to evade justice.

Investigative journalism in Mexico has a great impact on society and presence abroad, thanks to the international media that share news stories from Mexico. Sometimes they even unveil them, as, for example, when recently The New York Times ran a front page story about how Enrique Peña Nieto’s federal government had spied journalists and human rights activists. This is very important to us because investigative journalism in Mexico has no impact on the public sector — their investigations don’t lead to official investigations in the Attorney General’s Office or in the Comptroller’s office.

The Mexican government has practically given up on its obligation to investigate and officials have taken the path of complicity and protectionism for corrupt public officials and impunity for criminals, whether they are white-collar criminals, fraudsters who work for the government or drug traffickers.

The Mexican government has practically given up on its obligation to investigate and officials have taken the path of complicity and protectionism for corrupt public officials and impunity for criminals, whether they are white-collar criminals, fraudsters who work for the government or drug traffickers.

In Mexico all of this research remains in the reports of independent media, but it never makes it to court.

In this context, journalists who investigate issues of corruption and drug trafficking are vulnerable to threats, attacks, demands, smear campaigns and espionage. Recently espionage focused on journalists most critical of Peña Nieto’s administration was exposed, but this has also happened to activists who have openly criticized the actions of the government. Others have had to face audits.

The disdain the Presidency shows when investigative news stories are released reduces their replication in other media. This occurs along with the manipulation of official information and a communication strategy on the part of the government to minimize negative news in exchange for multi-million dollar advertising contracts with major news media outlets. This hasn’t only affected justice and democracy, but the right of the people to be well-informed.

In June of 2016, the new system of criminal justice in Mexico was implemented. It’s an adversarial, accusatory system, and it also includes a new catalog of criminal offenses that require preventive detention. In fact, nowadays a detainee can only be imprisoned after having committed one of seven crimes: organized crime, murder, rape, kidnapping, human trafficking, crimes committed with weapons and explosives and offenses against national security.

Criminal offenses such as violent assaults, and one of the most common in Mexico, carrying weapons that exclusively can only be used by the army and the armed forces, aren’t serious according to this new system, and don’t deserve prision.

With the modification of the list of offenses that warrant preventive detention, in the next few months around 69,000 prisoners could be let out of prison, many of them dangerous members of drug cartels but who were arrested while only carrying a gun. In fact, 30 percent of inmates in Mexican prisons have now regained their freedom, due to the change in the crime catalog.

In addition, while being an adversarial accusatory system, it always protects the suspect. In order for a detention to happen the police practically must stop the criminal while they are committing the crime. The research apparatus in Mexico is weak, unprofessional, and doesn’t have sufficient scientific tools, which is why the accused end up being released.

The same thing has been happening with notorious members of the drug cartels who were arrested in possession of firearms. They recover their freedom almost immediately. They’re the same petty criminals who rob, assault and harass the common citizen. In fact, the new system of criminal justice has been wryly considered to be a “revolving door,” because as soon as an offender is arrested he or she is released.

Other changes that contribute to criminal impunity in Mexico are restricting information. Now we know the name of the victims, but we can’t expose the offender. Judges may prohibit the publication of the names of offenders or their picture. And it doesn’t matter if we’re dealing with a public enemy.

Here’s an example: At the height of this new system, a few months ago the son of one of the leaders of the Sinaloa drug cartel escaped from prison, and when the Attorney General’s Office issued an alert for his search that included a reward, they omitted his full name, and his head shot was blurred. In practice this meant that the government wanted people to identify a faceless and nameless thug.

The criminals, especially the members of the drug cartels, have learned to circumvent justice with legal tools that the new system of criminal justice provides, and they have learned this faster than police agents have learned to implement it and help successfully produce an arrest warrant.

The armed criminals, who today don’t deserve to spend time prison in Mexico, are the authors of more than 104,000 execution style murders in the country in the last five years. They are the ones who have murdered journalists; they are the ones who control the territory with blood and lead. They’re the ones who today terrorize Mexico without facing any legal consequence.

Social Participation

Not all is lost.

With investigative journalism and a self-empowered society reporting what happens in Mexico in terms of corruption, impunity and drug trafficking, social organizations sponsored by major companies and business leaders have been created to contribute to freedom of expression and the rule of law.

Today, more than ever, there are research organizations that focus on missing persons, victims, corruption, public funds and violence. Hand in hand with independent journalists, these organizations are demonstrating what happens between the government and the criminals, and how federal, state or local funds are managed to the detriment of the population.

These same social groups and independent journalists have helped create institutions that supervise the actions of the government and access to information, putting in the hands of the citizens some of the spaces that were formerly in the hands of public officials. This way these institutions can obtain a better resolution of the cases. Certainly these steps are small in terms of the transparency of resources and information, but they are steps nonetheless.

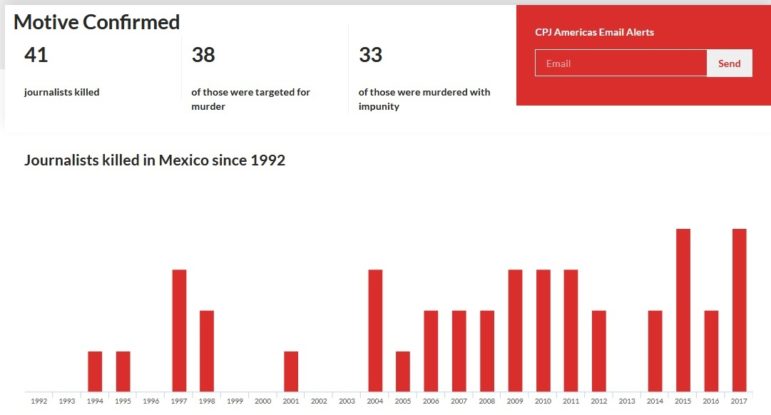

Murdered Journalists

Source: Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

In five years of Peña Nieto’s government, 37 journalists have been murdered. Their cases have been handled by a specialized prosecutor’s office that maintains a 4 percent level of effectiveness. In other words, 90 percent of the crimes against journalists remain in impunity.

The attacks against journalists come from organized crime and drug trafficking after drug lords are either exposed or after their relationship with government officials in cities and states are exposed.

According to Article 19 Mexico, in the last 17 years 109 journalists have been killed, 101 were men and eight were women. This does not count those who have been threatened — journalists who have had to leave their hometown and their jobs while facing the threats from the government or a cartel.

According to Article 19 Mexico, in the last 17 years 109 journalists have been killed, 101 were men and eight were women. This does not count those who have been threatened — journalists who have had to leave their hometown and their jobs while facing the threats from the government or a cartel.

At Zeta, the weekly news magazine where I work in Tijuana, Baja California, the climate of violence and crime has touched us all. Being a weekly publication that uses investigative journalism to focus on issues of government, politics, corruption, impunity, drug trafficking and the cartels, we have paid the consequences of exercising free speech and contributing to the rights people have of being well-informed.

This has included two murders and one attack, while more recently we have faced threats by two drug cartels, defamation on the part of the state government, and the pressure of audits and frequent notices from the Internal Revenue Service.

Héctor Félix Miranda

In 1988 one of our founders, Héctor Félix Miranda, was killed when he was on his way to the offices of Zeta. He was shot four times. The men who murdered him were released on May 1 2015, while the intellectual author of this murder was never tried, and now he has again hired the killers who were released from prison as part of his security team (which is the same job they had in 1988 when they killed this journalist).

In 1997, our other co-founder, Jesus Blancornelas, suffered an attack. Nine members of the Arellano Félix cartel were identified as the perpetrators of the attack, but none of them has been tried or imprisoned for the crime against the journalist.

Blancornelas survived nine more years, but his driver and bodyguard died during the shooting.

Francisco Ortiz Franco

Francisco Ortiz Franco, editor of Zeta, wrote a story in April of 2004 that included photographs and names of the new members of the Arellano Félix cartel. His investigative journalism led him to discover that the criminals had taken those pictures to have state judicial police credentials made out for them. Clearly that was the corrupt link between the drug traffickers and the government. Two months after that publication, members of the Arellano Félix cartel killed him.

For those who currently work for Zeta it hasn’t been easy. After 37 years of journalism, we continue to suffer the threat of criminals who are able to hide with the impunity the state provides.

Almost four months ago, in Culiacan, Sinaloa, Javier Valdez, a writer and a journalist, was shot to death. He was shot 12 times, obviously by members of the Sinaloa drug cartel. However, the Attorney General hasn’t provided the results of the criminal investigation. Nothing. Not a single word.

Javier Valdez

Javier’s murder, as well as my colleague’s assassination and the attack on our former director, are among the 96 percent of cases of journalists that remain in a state of impunity. The government has failed to investigate, the killers enjoy total impunity.

Those are the risks of doing investigative journalism in Mexico. You can end up dead; you will be threatened, spied on, defamed and at least audited.

But I insist: Not all is lost, social awareness has been generated with the publication of in-depth news stories and this has led us to take important steps and participate socially with the task of monitoring and denouncing acts of corruption and collusion with the government.

In this regard, we at Zeta — and I’m sure this is the position of all independent media in my country — will not tire, beyond the risks and threats, to do investigative journalism, assert our right to free speech, the right to have access to information, and thus, contribute to social justice in Mexico, a country that anxiously awaits a time of peace and justice for all where corruption and impunity can finally be a part of the past. To sum it all up, that’s why we do what we do.

Because I can’t imagine what would happen in Mexico without investigative journalism.

This post first appeared on the PEN Canada website and is cross-posted here with permission. It is adapted from the text of a September 13 lecture by Zeta magazine director Adela Navarro, sponsored by PEN and the Ryerson University International Issues Discussion Series, entitled “Investigative Journalism in a Dangerous Country.”

Adela Navarro is director of the weekly news magazine, Zeta, one of the only outlets in Mexico to regularly report on drug trafficking, corruption and organized crime. Over a 27-year career Navarro has seen colleagues killed for their reporting, and she lives and works under constant threat.

Adela Navarro is director of the weekly news magazine, Zeta, one of the only outlets in Mexico to regularly report on drug trafficking, corruption and organized crime. Over a 27-year career Navarro has seen colleagues killed for their reporting, and she lives and works under constant threat.