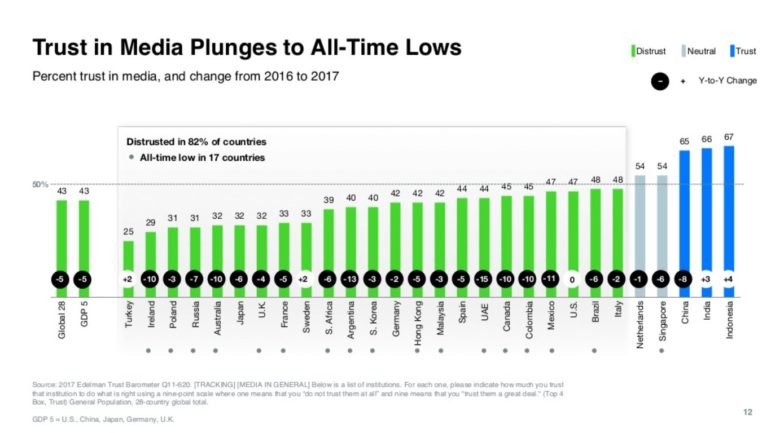

Across the globe, the public’s trust in the news media continues to decline. According to the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, 82 percent of 28 countries surveyed registered a decrease of trust in media from 2016 to 2017. Just 43 percent of those surveyed said they trust the media, down from 48 percent in 2016.

“It is up to the press to reflect on this [distrust],” explained Sérgio Dávila, executive editor at Folha de S.Paulo, one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers, during a panel about the “post-truth era” at the 12th Congress of Investigative Journalism in São Paulo this summer. “We are not immune to making mistakes, but we cannot be immune to self-criticism.”

“It is up to the press to reflect on this [distrust],” explained Sérgio Dávila, executive editor at Folha de S.Paulo, one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers, during a panel about the “post-truth era” at the 12th Congress of Investigative Journalism in São Paulo this summer. “We are not immune to making mistakes, but we cannot be immune to self-criticism.”

To recover that trust, news organizations have to invest even more in investigative journalism and transparency, the panel agreed. Folha de S.Paulo, for example, employs an ombudsman who reads and critiques the paper, with her corrections and fact-checks occupying as much space as the articles themselves.

The Washington Post is taking this one step further by explaining to their audience how some stories are written. The Post’s editor-in-chief, Martin Baron, said we have to distinguish fake news from mere journalistic mistakes.

“It is important to define what fake news is: it is false facts deliberately published; conspiracy theories with no bases,” Baron said. “It is not a mistake. Having defined that, fake news is a challenge to [the free press], to democracy and civil society. In a democratic society, we should disagree about some analyses, about some political issues, but we cannot disagree about facts. Fake news represents a serious threat.”

Fake news is not new in journalism, but thanks to social media, its impact is stronger than ever. With 2 billion users, Facebook is by far the largest social network — and the company is now collaborating with news outlets and organizations like First Draft News to minimize its role in proliferating fake news.

Luis Olivaldes, head of Latin American Media Partnerships at Facebook, explained the company will soon launch a tool that helps users improve their news literacy and better detect false articles.

“We are releasing a tool that helps train users to be more aware in their news consumption,” he said. “It is important that users can identify what is opinion, what is news, what is [satire]. We are building critical user sense.”

Later this year, Folha also plans to launch an educational digital platform to cultivate this same critical sense among its readers.

“We don’t know the exact format yet … but we will do more than launch a campaign about accurate journalism,” said Dávila. “We will [work] to teach people about how to get information on the internet, which sources are reliable, etc.”

When citizens have little trust in the media, press freedom is often more likely to erode. The panel maintained that press freedom is a necessary component of any democracy, helping to ensure that those in power are held accountable for their actions.

Operation Car Wash

Rodrigo Janot, Brazil’s former prosecutor general who is the main prosecutor in Operation Car Wash, an ongoing criminal investigation into corruption throughout the Brazilian government, reaffirmed press freedom’s importance. At the conference, he explained that a Brazilian investigative journalist tipped him off to some information that incriminated Eduardo Cunha, a former lower house speaker who was arrested last October.

“Without this journalist, we wouldn’t [have been] able to catch him,” Janot said. “Close that window, and you’re going to see damage to democracy. That is press freedom.”

According to Article 19, an NGO that advocates for freedom of expression, 105 journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000. Laura Castellanos, a Mexican investigative journalist who received the Latin American Award for Investigative Journalism for “Fueron los Federales (It was the Federal Police),” an article about the execution of 16 civilians in Apatzingan, Mexico, described the bleak landscape for Mexican journalists.

“In my country there is no democracy, it is not possible to change the institutions because it is a structural issue,” explained Castellanos. “It is systematic; it is a government that keeps its power through violence. And the violence is not just physical, but also includes preventing access to a good education, health care, housing … and investigative journalism has the job of showing that violence.”

“In my country there is no democracy, it is not possible to change the institutions because it is a structural issue,” explained Castellanos. “It is systematic; it is a government that keeps its power through violence. And the violence is not just physical, but also includes preventing access to a good education, health care, housing … and investigative journalism has the job of showing that violence.”

While the current state of journalism may be bleak, she said she sees the hunger for change in young journalists.

“We need the young views, young committed people who want to do investigative journalism, to know the background of our country to understand how we got here,” Castellanos said. “Many journalism students come to me and I trust in them, I support them, because we need many voices to cover all of it.”

This post first appeared on the IJNet website and is cross posted with permission.

This post first appeared on the IJNet website and is cross posted with permission.

Jéssica Cruz is a freelance journalist based in São Paulo, Brazil. She previously worked for Nine News Australia, Cidade Ocupada, and BBC World Service.