What appeared to be a case of money laundering done through a network of laundromats and car washes (in Portuguese, lava jato means “pressure washing”), turned out to be the largest corruption network in Brazilian history that ultimately extended to at least 12 countries. It has brought businessmen to justice and has shaken more than one government.

Just as authorities have had to ask for the cooperation of prosecutors in countries where those involved paid bribes, opened accounts or created ghost companies, the journalists covering this case have needed to seek help from their colleagues in other nations to obtain information, enrich their research and, above all, to understand the problem from a global perspective.

Just as authorities have had to ask for the cooperation of prosecutors in countries where those involved paid bribes, opened accounts or created ghost companies, the journalists covering this case have needed to seek help from their colleagues in other nations to obtain information, enrich their research and, above all, to understand the problem from a global perspective.

Journalists in Latin America who have covered the scandal agree that Lava Jato is a case that could not be tackled without collaboration. A web of corruption at that level could not be dealt with impartially from a single country, nor by a single media outlet.

“We, the journalists, always have to try to have an understanding, not only of the trees, but the vision of the whole forest,” said Flávio Ferreira, who has closely followed the case for the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S .Paulo.

The Knight Center talked with some of the Latin American journalists who have spent hours searching and sharing documents to produce independent and collaborative investigative reports on the Lava Jato scandal. In the first installment of this article, journalists explain the advantages of collaborating with colleagues from other countries, some of the obstacles they face and the power of establishing structured alliances so that their work has greater impact.

Opening a Box of Surprises

Coverage of the Lava Jato case began in Brazil, mainly as reporting on the national level. Only in the following years was it discovered that senior officials of the governments of Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva and Dilma Rousseff were involved, and the case became more relevant worldwide.

Those detained began to provide information due to plea-bargain testimony agreements they made with the justice system to reduce their sentences. The sewer was opened and information began to emerge about more bribes, officials and businessmen involved. This time, they were not only in Brazil.

A web of corruption at this level could not be dealt with impartially by a single country, nor by a single media outlet.

Before the term “Lava Jato” was even coined, Peruvian non-profit investigative journalism organization IDL-Reporteros had already uncovered the first signs of a corruption network. Its initial reports on the subject revealed the ease with which Brazilian companies like Odebrecht won contracts for public works in Peru.

“In 2011, we published the first story on Odebrecht, on overcharges related to the firm and indications of possible corruption,” said Gustavo Gorriti, director of IDL-Reporteros, which said it’s the first media organization to have recognized the transnational implications of the case. “When the Lava Jato case began to emerge, we saw very clearly that it affected many things beyond Brazil, since it was clear that almost all of those Brazilian companies outside Brazil were organized with one another. Because of this, the case had implications across Latin America.”

It was then that international journalistic collaboration became necessary.

“Many times when I was doing the research,” Ferreira said, “I found references to a company or person who was outside Brazil, but I thought ‘I do not have a way to do this, I do not have the hands to do this, I do not know anyone.’ I had to look for a contact, someone outside Brazil, because it was complicated to do it alone.”

“Many times, I found references to a company or a person outside Brazil. I had to look for a contact outside Brazil because it was complicated to do it alone.” — Flávio Ferreira

“At Folha, there was a separation. The topics related to Lava Jato in Brazil were published in the national section and cases related to other countries were being published in the international section. Correspondents in other countries were the ones who had the responsibility of doing this coverage, so it was fragmented coverage.”

As more information came to light, more specialized journalism was required. The news articles and the work of the correspondents were not enough to portray the magnitude of the problem. The journalists realized that not only was it necessary to collaborate with colleagues from other countries, but also to do investigative journalism that addressed the issue in greater depth.

The defendants provided evidence to the justice system, and media outlets began to write data journalism stories with information from those documents. But some media outlets also began to carry out investigations on their own, without relying on information released from the authorities’ investigations.

“General journalism in Latin America was not producing coverage from the basis of investigative journalism, beyond the factual news, where data from Brazilian authorities or public institutions were regurgitated by the media outlets,” said Milagros Salazar, director of the Peruvian investigative journalism site Convoca, which has produced special projects dedicated to the Lava Jato case. “Recently, most media outlets in the region, both traditional media and independent investigative journalism media, have begun to look at the subject in greater depth and became interested in cases.”

Folha’s Lava Jato stories were published in the national section while those overseas wrote for the international section, resulting in fragmented coverage.

In December 2016 the US Department of Justice revealed documents containing the testimony of 77 executives of the Odebrecht conglomerate, accompanied by documentary evidence, in which they admitted the payment of bribes of about $788 million in 12 countries in Latin America and Africa. The information was provided to the Brazilian authorities, and the prosecutors of the countries mentioned requested access to these documents. The media also sought access to them, but it was very complicated to do so from their countries.

“At Folha, we obtained the documents from the Supreme Court [of Brazil],” Ferreira said. “There were about 8,000 documents that I could share with colleagues from other countries and they had the opportunity to examine all the documents as if they were in Brazil.”

Access to these documents meant the beginning of a series of investigative reports focused on the cases in each country. Reporters from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina and the Dominican Republic, among others, were able to do specific searches on bribes in their countries and local people involved.

Demonstrators protest on Copacabana Beach in favor of Lava Jato and Judge Sergio Moro. (By Tomaz Silva (Agência Brasil)

“First, we had to find a Brazilian ally that would help us to understand this anti-corruption operation,” Raúl Olmos, a journalist with the site Mexicans against Corruption and Impunity, told the Knight Center. “Second, that would guide us on how to have documentation. And thirdly, that would connect us with people they knew could inform us or give us guidance.

“This alliance was necessary because otherwise it would not have been possible to get the information so quickly, and it would have been a great expense to travel to Brazil constantly to obtain data. Collaborative journalism allows those of us from different countries to begin to see a single theme. “

However, sometimes it is also necessary to travel and meet physically for courses and seminars where journalists take the opportunity to organize, share information and catch up on their investigations. Such was the case of the Latin American Meeting of Investigative Journalists on Illicit Financial Flows organized by Convoca and the nonprofit Red Latinoamericana sobre Deuda, Desarrollo y Derechos (Latin American Network on Debt, Development and Rights), whose second gathering was held in Lima, Peru in May. At the meeting, the journalists explained the progress of the Lava Jato case in their countries and consulted experts in the area of illicit money flows.

The Power of Alliances

Transnational collaboration among journalists, like Lava Jato, has many advantages. In addition to reducing the cost of investigations for each media outlet and allowing the exchange of sources and contacts, a great advantage is that they allow for a better global understanding of the case.

On the flip side of the coin, this case also presents many obstacles for journalists seeking to reveal information. Several journalists agree that the obstacles with the highest cost are hindrances to accessing information. When it comes to information that is sensitive for governments, the authorities of the different countries complicate media outlets’ access to judicial investigations.

Besides reducing costs and allowing the exchange of sources and contacts, transnational journalism collaborations allow for a better global understanding of the case.

“The main obstacle remains the authorities’ rigidity in making the documents involving Odebrecht public, specifically many that would have to be public, such as contracts, agreements, extensions,” Olmos said. “We understand that because an investigation is under way it is not possible to make public all the details of the contracts, but we ask that we be given a public version.”

Sometimes, it’s not only that authorities will not help journalists access the information, they also become antagonistic, trying to hide data, manipulating information that is revealed or even disqualifying the veracity of what is published. This forces the journalists to shield themselves in order to leave zero room for doubt about their work.

A recent report from IDL-Reporteros revealed Marcelo Odebrecht had recommended financing the presidential campaign of Keiko Fujimori in Peru, but was denied by that country’s authorities. It was later discovered that the Peruvian prosecutor’s office was trying to hide that information.

Federal police board seized material at Eletronuclear, Operation Radioactivity, the 16th phase of Operation Lava Jato. (By Fernando Frazão/Agencia Brasil (Agência Brasil) [CC BY 3.0]

One of the ways in which journalists in Latin America have faced these difficulties in accessing public information is by forming more official partnerships. Journalists, media outlets and non-governmental organizations interested in having more complete coverage have become allies in different collaborative projects.

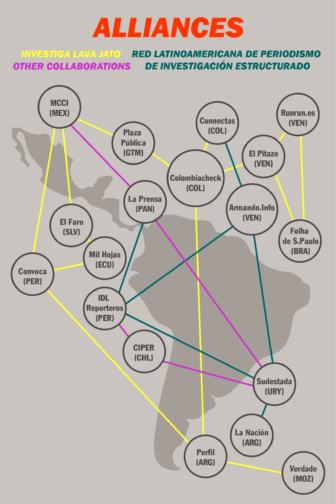

Among the most recent is Investiga Lava Jato, a project led by Convoca (from Peru) and Folha de S.Paulo (from Brazil). Journalists participate from Diario Perfil (Argentina), Fundación Mil Hojas (Ecuador), Plaza Pública (Guatemala), El Faro (El Salvador), Mexicans against Corruption and Impunity (Mexico), RunRun.es and El Pitazo (from Venezuela) and Jornal Verdade (from Mozambique). They count on the collaboration of Colombiacheck for fact-checking and ICFJ’s Regional Initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas and Connectas for support with data.

Among the most recent is Investiga Lava Jato, a project led by Convoca (from Peru) and Folha de S.Paulo (from Brazil). Journalists participate from Diario Perfil (Argentina), Fundación Mil Hojas (Ecuador), Plaza Pública (Guatemala), El Faro (El Salvador), Mexicans against Corruption and Impunity (Mexico), RunRun.es and El Pitazo (from Venezuela) and Jornal Verdade (from Mozambique). They count on the collaboration of Colombiacheck for fact-checking and ICFJ’s Regional Initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas and Connectas for support with data.

Investiga Lava Jato was launched in June 2017 with the purpose of developing and disseminating in-depth reports on the corruption network. The investigations presented have been possible in part thanks to court documents shared by Folha de S.Paulo, which were uploaded on a platform called Overview that allows for searching, viewing and reviewing documents in any format. This greatly facilitated the ability of journalists from all corners of Latin America to access these documents.

Previously, IDL-Reporteros (also from Peru) joined the newspaper La Prensa (from Panama), the newspaper La Nación (from Argentina), the site Armando.info (from Venezuela) and the site Sudestada (from Uruguay) to form an alliance they called the Latin American Network of Structured Investigation. The name was a tongue-in-cheek reference to the so-called Structured Operations Division of Odebrecht, which allegedly was the department responsible for managing bribes.

The main obstacle remains the authorities’ rigidity in making documents public, and sometimes hiding or manipulating information or disqualifying the veracity of media reports.

The IDL-Reporteros network functions as a virtual newsroom in which there is a constant exchange of documentation, information and sources to contribute to other journalists’ investigations.

“We establish relationships with journalists, not media outlets,” Gorriti said. “The primary relationship is with the investigative reporter. It has to be people with a lot of experience, and they must be absolutely reliable people. This is handled in a very horizontal manner, but on the basis of total trust. We have understood from the outset that this is the most important corruption investigation in Latin American history and that it will depend on investigative journalism as to whether or not it has an effect, and we are seeking to ensure it has an effect. “

Both projects counted on the collaboration of the Connectas organization, which helped in the dissemination of investigative journalism, but above all, has contributed with supporting data on the companies involved in the corruption scheme. The organization has spent the last few years tracing information on the companies, the executives behind them and the offshore companies involved in Lava Jato.

“There is a lot of data related to this subject,” Sol Lauría, a data researcher at Connectas, told the Knight Center. “And so we are making a database with a lot of the companies that were appearing in order to see the offshore structure, how it operated in this universe and how they handled all the companies that were opening in every part of the world.” She added that these are official data obtained through judicial investigations or leaks.

Another platform that has been very useful in giving media access to documents on the case is #LavaJota, a project from the Brazilian legal news website JOTA.Info which has the backing of Transparency International. It is a database containing documents and contracts for the hundreds of legal processes that make up the Lava Jato operation.

Another platform that has been very useful in giving media access to documents on the case is #LavaJota, a project from the Brazilian legal news website JOTA.Info which has the backing of Transparency International. It is a database containing documents and contracts for the hundreds of legal processes that make up the Lava Jato operation.

“Lava Jato has done a very valuable thing, which is bringing those processes together in one place,” Carlos Eduardo Huertas, director of Connectas, told the Knight Center. “It has released information without giving benefits to any one media outlet, and I think that has resulted in the case being covered differently.”

This story originally appeared on the Journalism in the Americas’ blog and is reproduced here with permission.

César López Linares is studying toward his master’s in journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. He has worked as a journalist for Reforma, Todo Austin, Texas Music Magazine and the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

César López Linares is studying toward his master’s in journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. He has worked as a journalist for Reforma, Todo Austin, Texas Music Magazine and the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.