Researchers and journalists often need to verify user-generated video content from social networks and file sharing platforms, such as YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. But there is no silver bullet that is able to verify every video, and it may be nearly impossible to verify some videos, short of acquiring the original file from the source.

(For additional articles on verifying videos, see the GIJN Fact-Checking and Verification resource page.)

However, there are methods which can help to verify most content, particularly to ensure that videos showing breaking news events are not recycled from previous incidents. There are already numerous guides available online for verifying video, most notably in the Verification Handbook.

However, there are methods which can help to verify most content, particularly to ensure that videos showing breaking news events are not recycled from previous incidents. There are already numerous guides available online for verifying video, most notably in the Verification Handbook.

This guide will include some additional techniques frequently used by the Bellingcat team, including ways to work around the limitations of available tools. See Bellingcat’s Guide to Using Reverse Image Search for Investigations (2019). After reading this guide, hopefully you will not only know how to use this toolset, but also how to get creative and avoid dead ends.

Flawed, but Useful: Reverse Image Search

The first step in verifying video content is the same as verifying images — run a reverse image search through Google or other services, such as TinEye. Currently, there are no freely available tools that allow you to reverse search an entire video clip the same way we can with image files, but we can do the next best thing by reverse image searching thumbnails and screenshots. People who create fake videos are rarely creative, and will most often re-share an easy-to-find video without any obvious signs that it does not fit the incident, such as a news chyron or an audio track with someone speaking a language that does not fit the new incident. Because of this, it is relatively easy to fact check recycled videos.

The first step in verifying video content is the same as verifying images — run a reverse image search through Google or other services, such as TinEye. Currently, there are no freely available tools that allow you to reverse search an entire video clip the same way we can with image files, but we can do the next best thing by reverse image searching thumbnails and screenshots. People who create fake videos are rarely creative, and will most often re-share an easy-to-find video without any obvious signs that it does not fit the incident, such as a news chyron or an audio track with someone speaking a language that does not fit the new incident. Because of this, it is relatively easy to fact check recycled videos.

There are two ways to conduct this search. The first is to manually take screenshots of the video, best either at the very beginning or during key moments in the clip, and then upload them onto a reverse image search service, such as Google Images. The second is to rely on the thumbnails generated by the video host, most often YouTube.

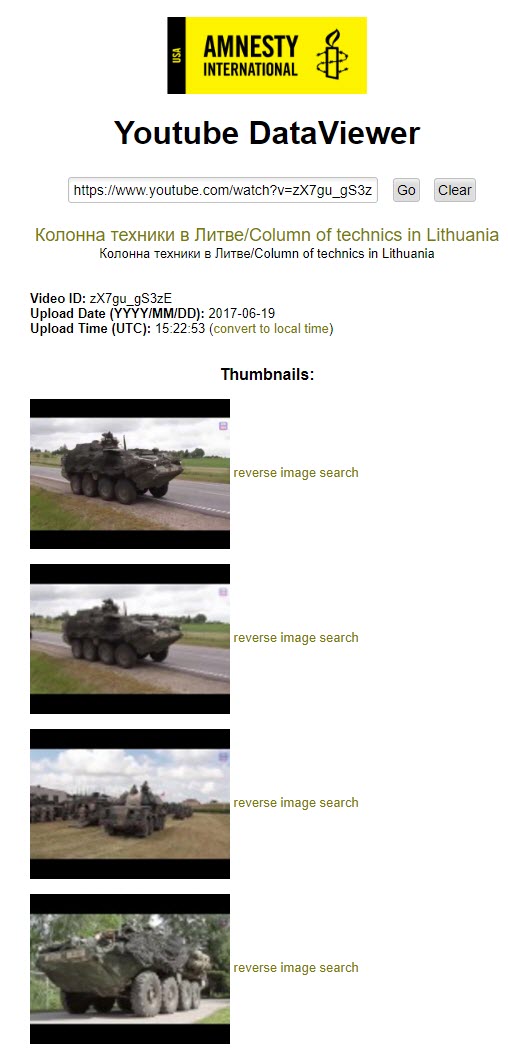

There is no easy way to determine which frame a video will automatically select as a thumbnail, as Google developed a complex algorithm for YouTube to select the best thumbnail for an uploaded video. (For more on this, see the Google Research Blog entry on the topic here.) Perhaps the best tool to find these thumbnails is Amnesty International’s YouTube DataViewer, which generates the thumbnails used by a video on YouTube and allows you to conduct a reverse image search on them in one click.

There is no easy way to determine which frame a video will automatically select as a thumbnail, as Google developed a complex algorithm for YouTube to select the best thumbnail for an uploaded video. (For more on this, see the Google Research Blog entry on the topic here.) Perhaps the best tool to find these thumbnails is Amnesty International’s YouTube DataViewer, which generates the thumbnails used by a video on YouTube and allows you to conduct a reverse image search on them in one click.

For example, a YouTube aggregator called Action Tube recently posted a video supposedly showing a convoy of military equipment in Lithuania, but without providing any source material for it. Additionally, there are no indications of when the video was filmed, meaning that it could have been from yesterday or five years ago. The video was eventually taken down from YouTube.

If we search for this video on the Amnesty International tool, we find out the exact date and time that Action Tube uploaded the video, along with four thumbnails to reverse search to find the original source of the video.

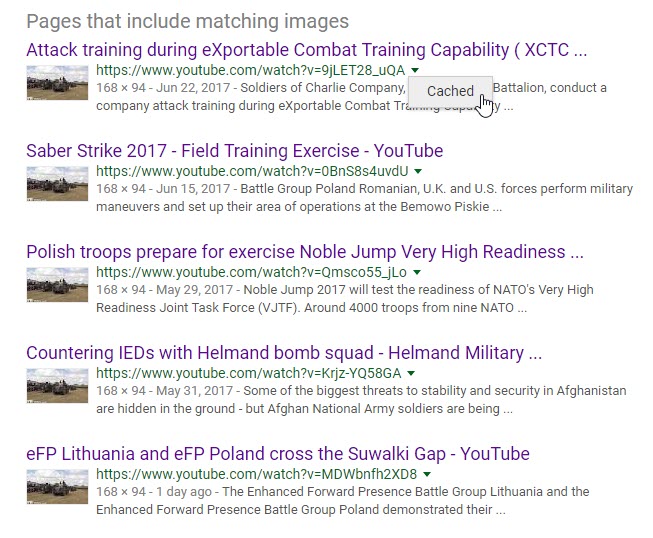

None of the results gives us a direct hit on the original source. However, a number of the results on the third thumbnail point to videos that showed this thumbnail on the page at one time. If you click these videos, you may not find this thumbnail, as the results for the “Up next” videos on the right side of a YouTube page are tailored for each user. However, the video with that thumbnail was present at the time when Google saved the results, meaning that you can find this video on the cached page.

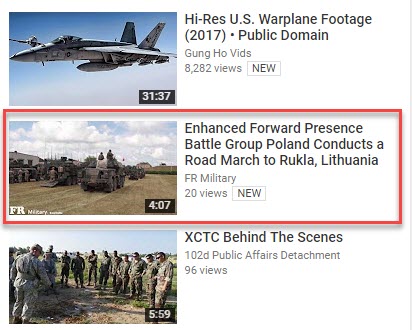

None of the results gives us a direct hit on the original source. However, a number of the results on the third thumbnail point to videos that showed this thumbnail on the page at one time. If you click these videos, you may not find this thumbnail, as the results for the “Up next” videos on the right side of a YouTube page are tailored for each user. However, the video with that thumbnail was present at the time when Google saved the results, meaning that you can find this video on the cached page. Again, none of these five results are the source of the video we are looking for, but when Google cached its snapshot of the page, the thumbnail video for the source was present on these videos’ pages. When we viewed the cached page for the first result above, we see the source for the video posted by Action Tube, with the title “Enhanced Forward Presence Battle Group Poland Conducts a Road March to Rukla, Lithuania.”

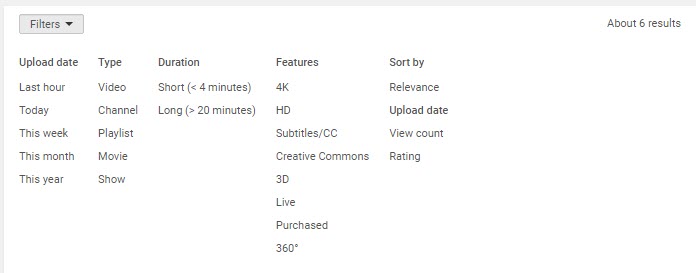

Again, none of these five results are the source of the video we are looking for, but when Google cached its snapshot of the page, the thumbnail video for the source was present on these videos’ pages. When we viewed the cached page for the first result above, we see the source for the video posted by Action Tube, with the title “Enhanced Forward Presence Battle Group Poland Conducts a Road March to Rukla, Lithuania.” We now have all the information we need to track down the original video and verify that the Action Tube video does indeed show a recent deployment of military equipment in Lithuania. After we search the title of the video found in the thumbnail search result, we find six uploads. If we sort them by date, we can find the oldest upload, which served as the source material for Action Tube.

We now have all the information we need to track down the original video and verify that the Action Tube video does indeed show a recent deployment of military equipment in Lithuania. After we search the title of the video found in the thumbnail search result, we find six uploads. If we sort them by date, we can find the oldest upload, which served as the source material for Action Tube.

If we do a simple search on the uploader, we see that he has written articles for the US Army website about NATO activities in Europe, meaning that he is likely a communications official, thus lending additional credence to his upload being the original source for Action Tube.

Creativity Still More Powerful than Algorithms

While reverse-image searching can unearth many fake videos, it is not a perfect solution. For example, the video below, which has over 45,000 views, supposedly shows fighting between Ukrainian soldiers and Russian-backed separatist forces near Svitlodarsk in eastern Ukraine. The title translates to “Battle in the area of the Svitlodarsk Bulge in the Donbas (shot from the perspective of the Ukrainian Armed Forces).” We can see a lot of gunfire and artillery shots, while the soldiers seem to be laughing along with the fighting.

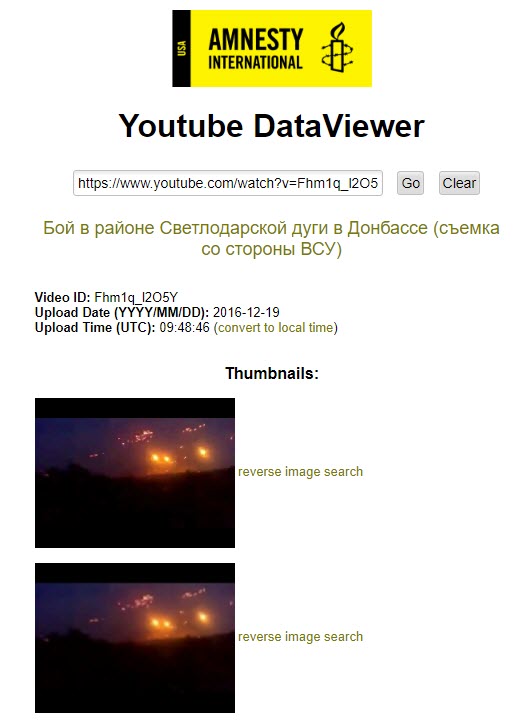

When we enter the video’s URL into Amnesty International’s tool, we see the exact date and time it was uploaded, along with thumbnails that we can reverse search.

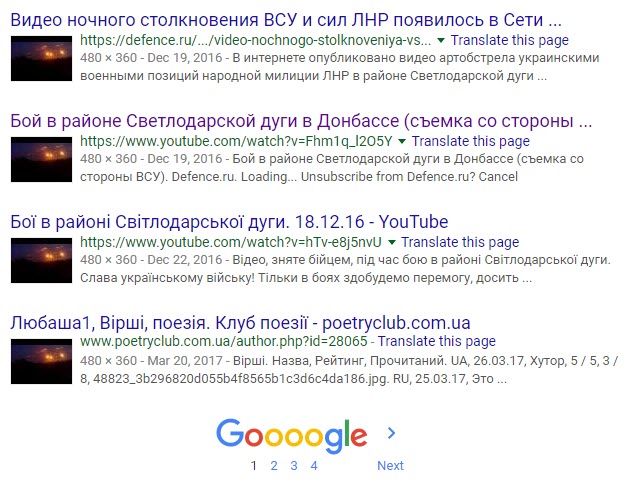

When looking through the results, almost all of them are for around the same time that the video was uploaded, giving the appearance that the video could genuinely show fighting near Svitlodarsk in December 2016.

However, the video is actually from a Russian military training exercise from 2012.

Even the most creative uses of reverse Google image search and Amnesty International’s tool will not find this original video in the results, except in articles describing the debunking after the fake videos were spread. For example, if we search the exact title of the original video (“кавказ 2012 учения ночь,” meaning “Kavkaz 2012 night training,” referring to the Kavkaz 2012 military exercises), along with a screenshot from the video, we only find results for the fake Svitlodarsk video. Knowing that this video was fake required one of two things: a familiarity with the original video, or a keen eye (or ear) telling you that the laughing soldier did not correspond with the supposed battle taking place.

So, what is to be done? There is no easy answer, other than searching creatively.

One of the best ways to do this is to try thinking like the person who shared a potentially fake video. With the example above, the laughing soldier gives you a clue that perhaps this is not real fighting, leading to the question of under what circumstances a Russian-speaking soldier would be filming this incident and laughing.

If you wanted to find a video like this, what would you search for? You would want a video at night probably, so that there would be fewer identifiable details. You would also try looking through footage of spectacular-looking fighting, but not something easily recognizable to Ukrainians or Russians following the war in the Donbas — so, finding videos of exercises from the Russian, Ukrainian or Belarusian army could fit the bill, unless you found war footage from another country and dubbed it with Russian speakers. If you search the Russian phrases for “training exercises” and “night,” this video would be the very first result. If you were not able to stumble your way to the original video, the best way to verify this video would have been to contact the person who uploaded it.

Be a Digital Sherlock with An Eye for Detail

Using digital tools to verify materials is inherently limited as algorithms can be fooled. People often use simple tricks to avoid detection from reverse image searches — mirroring a video, changing the color scheme to black and white, zooming in or out and so on. The best way to check for this is an eye for detail to make sure the surroundings in the video are consistent with the incident at hand.

On September 19, 2016, reports came in that the man responsible for three bomb explosions in New York City and New Jersey was arrested in Linden, New Jersey. A few photographs and videos emerged from different sources, including the two below showing the suspect, Ahmad Khan Rahami, on the ground surrounded by police officers.

The exact address in Linden, NJ where he was arrested was not clear, but it was a safe bet that these two photographs were real, considering how they showed roughly the same scene from two perspectives. The video embedded below also emerged from a local citizen. Clearly, the video is real, as it was shared widely on news outlets throughout the day, but how could we have done lightning-fast verification to know it was real in the middle of the breaking news situation?

The exact address in Linden, NJ where he was arrested was not clear, but it was a safe bet that these two photographs were real, considering how they showed roughly the same scene from two perspectives. The video embedded below also emerged from a local citizen. Clearly, the video is real, as it was shared widely on news outlets throughout the day, but how could we have done lightning-fast verification to know it was real in the middle of the breaking news situation?

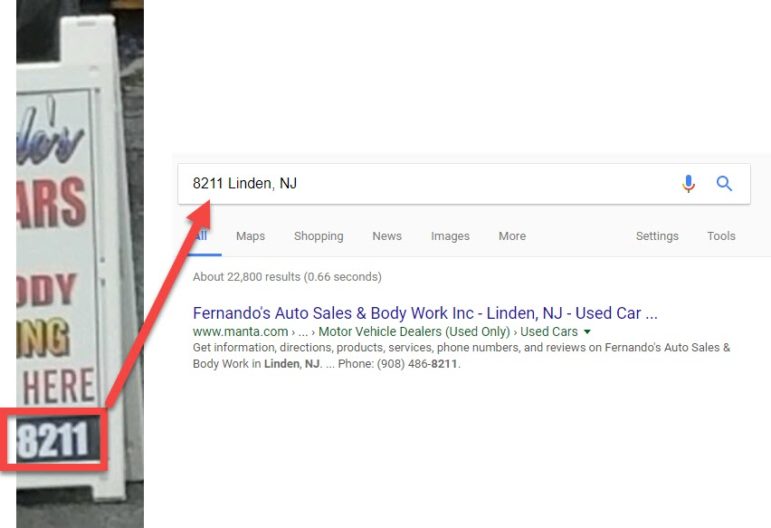

We can figure out where Rahami was arrested quite quickly from the two photographs. In the bottom-left corner of the second photograph, we can see an advertisement with four numbers (8211), along with fragments of words like “-ARS” and “-ODY.” We can also see there is a junction for Highway 619 nearby, letting us drill down the location more precisely. If we search for a phone number with 8211 in it in Linden, NJ, we get a result for Fernando’s Auto Sales & Body Work, which completes the “-ARS” and “-ODY” fragments — cars and body. Additionally, we can find the address for Fernando’s as 512 E Elizabeth Ave in Linden, NJ.

Checking the address on Google Street View lets us quickly double check that we’re on the right track.

Checking the address on Google Street View lets us quickly double check that we’re on the right track.

Left: Photograph of suspect being arrested in Linden, NJ. Right: Google Street View imagery of the same location

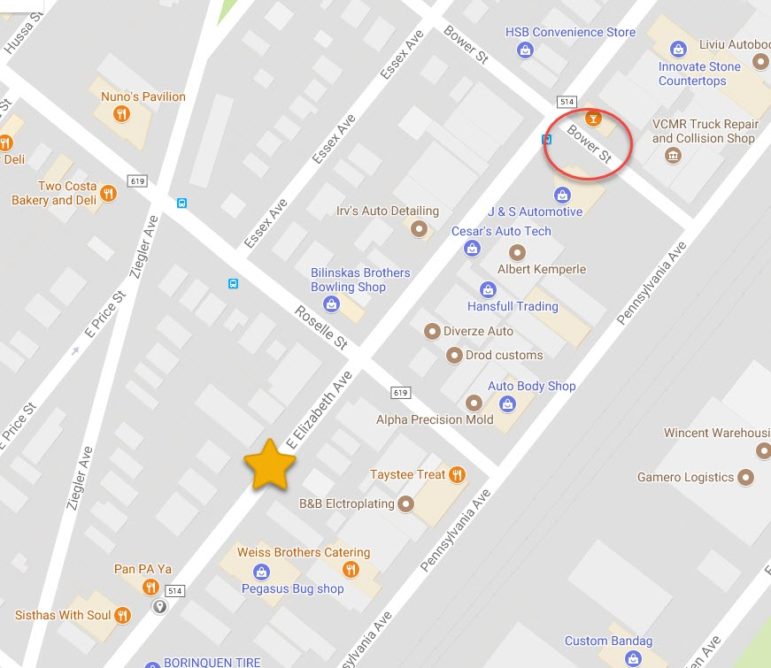

In both of the photographs and in the video in question, the weather is the same – overcast and damp. Twenty-six seconds into the video, the driver passes a sign that says “Bower St” and another Highway 619 junction sign, giving us a geographical location to cross-check against the location we found in the two photographs.

A quick glance at Google Maps shows you that Bower Street intersects with East Elizabeth Ave, where the suspect was arrested near the auto repair shop (represented by the yellow star).

A quick glance at Google Maps shows you that Bower Street intersects with East Elizabeth Ave, where the suspect was arrested near the auto repair shop (represented by the yellow star).

If you have time, you can drill down the exact location where the video was filmed by comparing the features on Google Street View to the video.

While there seems to be a lot of work involved in each of these steps, the entire process should not take much longer than five minutes if you know what to look for. If you do not have access to the eyewitness who provided video materials from the incident, verifying their footage will only require an attentive eye for detail and some legwork on Google Maps and Street View. Verifying video materials should be a routine part of reporting, as well as sharing content on social networks, as this is one of the quickest ways that fake news can be spread.

Discerning the Signal Through the Noise

A lot of effort and skill is required to digitally alter videos, which need the addition or subtraction of elements while still looking natural. Often, videos are altered not just to elude fact checkers, but to avoid the detection of algorithms looking for copyrighted content. For example, movies, television shows or sporting events may be uploaded to YouTube with the video mirrored, so that it is still watchable (albeit a bit off-putting), but avoid Digital Millennium Copyright Act violations. The best way to quickly detect if a video has been mirrored is to look for any text or numbers, as they will look strange after being flipped.

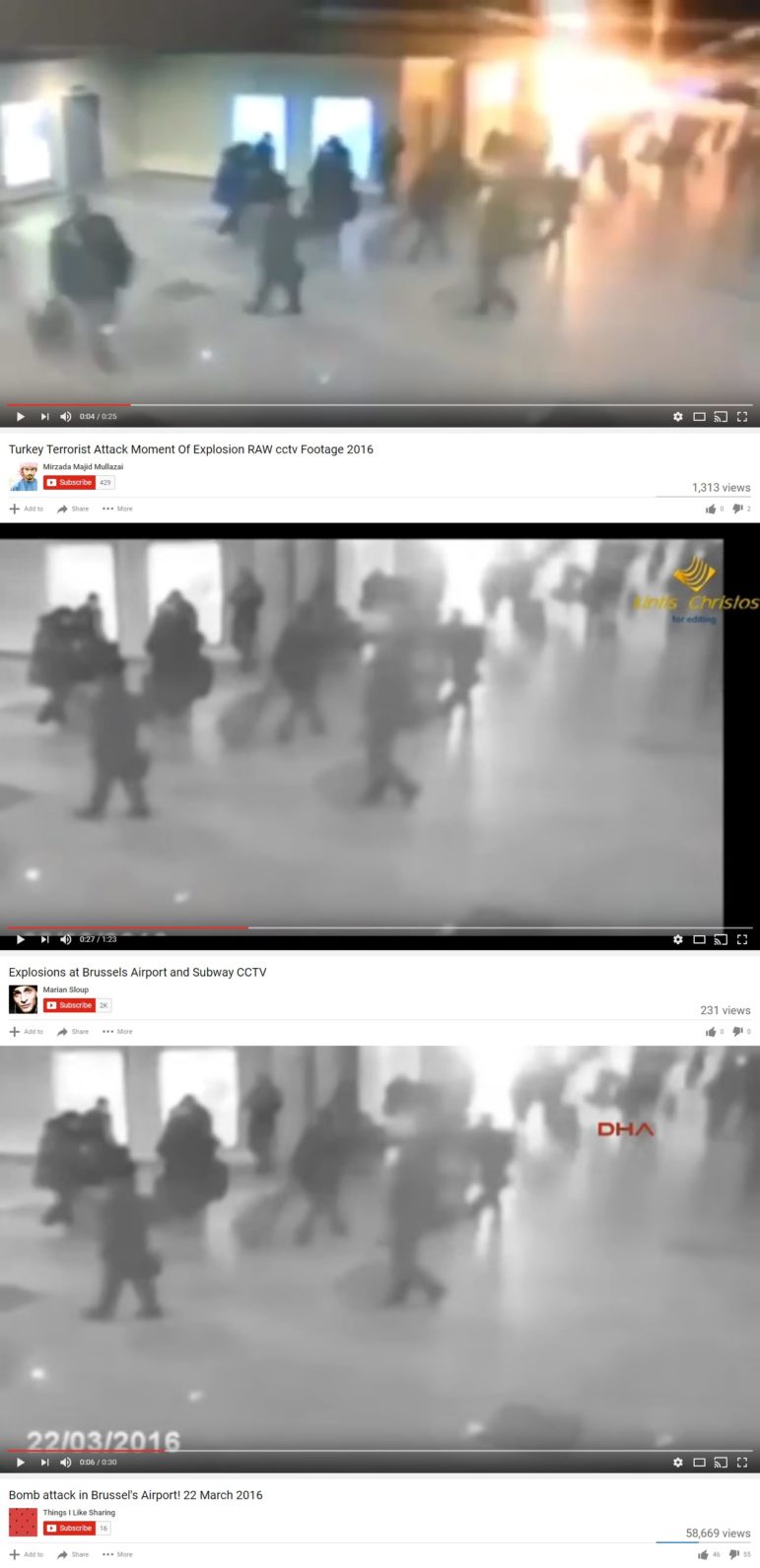

In the series of screenshots below, 2011 footage of an attack in Moscow’s Domodedovo airport was re-purposed into fake videos about the airport attacks in Brussels and Istanbul. Some of the effects the fakers used included zooming in on segments of the video, adding fake time stamps, and changing the color scheme to black and white. Additionally, gaudy logos are often added on top of the footage, making it even more difficult to reverse image search.

There is no easy way to detect these as fakes through tools — you need to rely on common sense and creative searching. As with the Russian military training video re-purposed as fresh battle footage, you need to think about what someone making fake video would search for to find source material. Searching the terms “airport explosion” or “CCTV terrorist attack” will give you the Domodedovo airport attack footage, providing a far faster result than playing with screenshots to bring back results in a reverse Google image search.

No Silver Bullet in Sight

Many see technological advancements as a future remedy to fake news and content, but it is hard to imagine any digital methods which will be able to discover fake videos and verify content with anything close to complete precision. In other words, an arms race between developers and semi-creative fake video creators is a losing battle at this point, barring strict content sharing controls on social networks and YouTube. While the digital tool set is important in verifying fake content, the creative one is even more important.

This post originally appeared on the Bellingcat website and is cross-posted here with permission.

Aric Toler has been working at Bellingcat since 2015. He focuses on verification of Russian media, the conflict in eastern Ukraine, Russian influence in the American/European far-right and the ongoing investigation into MH17.

Aric Toler has been working at Bellingcat since 2015. He focuses on verification of Russian media, the conflict in eastern Ukraine, Russian influence in the American/European far-right and the ongoing investigation into MH17.