Editor’s Note: Between November 2014 and February 2015, researchers conducted interviews with 27 investigative journalists, editors, legal experts and freedom of expression specialists from 17 countries for a section in the UNESCO report “Protecting Sources in the Digital Age” which deals with the difficulties investigative journalists face with source protection, and the ways they are changing their practices in response. Following is an edited excerpt from the report, which was authored by Julie Posetti.

Editor’s Note: Between November 2014 and February 2015, researchers conducted interviews with 27 investigative journalists, editors, legal experts and freedom of expression specialists from 17 countries for a section in the UNESCO report “Protecting Sources in the Digital Age” which deals with the difficulties investigative journalists face with source protection, and the ways they are changing their practices in response. Following is an edited excerpt from the report, which was authored by Julie Posetti.

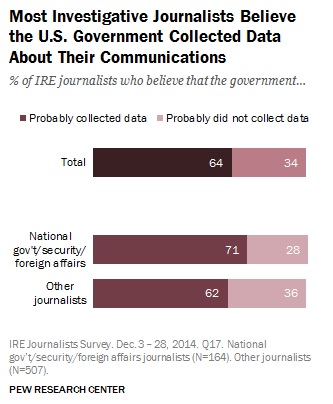

In February 2015, the Pew Research Center released the results of a survey on “Perceptions of vulnerability and changes in behavior” among members of the US-based Investigative Reporters and Editors. Their research found that 64 percent of investigative journalists surveyed believed the US government collected data about their communications. The figure rose to 71 percent among national political reporters and those who report on foreign affairs and national security issues.

A full 90 percent of the of US investigative journalists who responded to the Pew survey believed that their internet service provider (ISP) would routinely share their data with the National Security Agency, while more than 70 percent reported they had little confidence in ISPs’ ability to protect their data. As a result, 49 percent said over the previous year they changed the way they stored and shared sensitive documents, while 29 percent changed the way they communicated with journalists and other editors.

In another study, Human Rights Watch interviewed 46 senior national security journalists from major US news organizations, revealing the steps being taken to keep communications, sources and other confidential information secure in light of surveillance revelations. That study concluded that in the US the combination of increased surveillance and government prosecution of leaks was having a big effect on the news gathering practices of national security reporters and their news organizations.

In another study, Human Rights Watch interviewed 46 senior national security journalists from major US news organizations, revealing the steps being taken to keep communications, sources and other confidential information secure in light of surveillance revelations. That study concluded that in the US the combination of increased surveillance and government prosecution of leaks was having a big effect on the news gathering practices of national security reporters and their news organizations.

“Journalists are struggling harder than ever before to protect their sources, and sources are more reluctant to speak,” the study noted. “This environment makes reporting both slower and less fruitful.”

A Golden Age

Gerard Ryle, the director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), said the digital era is a “Golden Age for journalism.”

Gerard Ryle, the director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), said the digital era is a “Golden Age for journalism.”

“Technology is allowing information to be leaked on a vast scale, a scale that couldn’t possibly have been imagined,” Ryle said. “For me as a journalist, we’re in boom times, because you’re able to get information that’s incredibly detailed and you’re able to get stories that you couldn’t possibly [get before].”

Founder of the Arabic Media Internet Network, Daoud Kuttab, echoed Ryle’s view.

“On the one hand, I think it has accelerated and widened the amount of data available to everyone and made it very easy to transfer information and documents. But at the same time governments are able to invade your privacy much easier and get information.”

Editor-in-Chief of Argentina’s La Nacion, Carlos Guyot, also acknowledged the significant benefits of digital era investigative reporting involving confidential sources, including access to leaked documents that would have been impossible to get even five or ten years ago, although he added a caveat:

“New technologies bring new challenges with them, but also new opportunities, like encrypted conversations via new software, although this must be combined with old fashioned practices,” Guyot said. “There is nothing like a face-to-face meeting with a source. Our main investigative reporter drove for three hours to a different city for a 15 minute conversation with a source and drove back to our newsroom. If we are willing to endure the challenges, we can still do good journalism.”

Journalism after Snowden

Bolivian investigative journalist Ricardo Aguilar expressed serious concern about the reliability of legal source protection in the digital era.

“Mass surveillance, data retention and the appeal of the ‘national security’ category leaves the protection of secret sources in latent vulnerability,” Aguilar said.

Executive editor of the Washington Post, Martin Baron, said his concern about surveillance of newspapers’ internal communications led to significant changes to newsroom practices during the Post’s coverage of the Snowden story.

“I didn’t expect that we would have to be communicating with each other in an encrypted fashion and yet on many occasions we did just that. And on many occasions when we had meetings everybody turned off their cellphone, or left their cell phones behind.”

Director of the investigative unit at Sweden’s national public radio (SR), Fredrik Laurin, was concerned about the risk of police seizing digital content due to gaps in source protection legislation in his country. He described undertaking extraordinary digital security measures to comply with Sweden’s strict laws requiring journalists to protect their sources.

Chilling Effect on Sources

Umar Cheema, the co-founder of Pakistan’s Centre for Investigative Reporting, told researchers that the threat of surveillance is having a major chilling effect on sources.

“Certainly, source insecurity is a major challenge and it is mostly [connected] with the stories about national security and high-profile government figures,” he said.

Umar Cheema during the IJAsia16 conference in Nepal.

Cheema said his status guaranteed he is under surveillance and that his sources know it. He said some sources approached him in the belief that he is the right person to be taken into confidence, while others hesitated because they feared that he was under surveillance and that “any contact with me will put them on radar screen.”

Former editor-in-chief of The Guardian, Alan Rusbridger, said increased risk of exposure is having a direct impact on the willingness of confidential sources to share information with journalists. He said it had led to “a massive drying up of people willing to take the risk of talking to news organizations.”

International editor of Algeria’s El Watan newspaper, Zine Cherfaoui, said sources are more reluctant to speak and increasingly require face-to-face meetings.

“To really discuss with people we prefer to avoid electronic means or social networks. The Snowden affair turned upside down the work of journalists. It’s harder to speak to people. We really have to go out and meet them. It’s face-to-face.”

In Bolivia, La Razon’s Aguilar reported that sources have adjusted their behavior, intensifying “precautions ranging from avoiding using the phone to talk to me to not exchanging any form of correspondence, or digital messaging.” However, he said “the digital age has nothing to do with the ‘chilling effect’ because it existed by itself beyond the control of the internet.”

The cost of digital security technology, training and legal fees in relation to digital issues is having a chilling effect on investigative journalism in some cases.

Rusbridger said The Guardian spent about a million pounds more a year on legal fees than they did five years ago, which reduces the budget to do reporting. “The bills on these things just mount and mount and mount and mount, so you can easily be spending tens or hundreds, hundreds of thousands of pounds trying to get a story into the paper,” he said. “And of course once you get onto secure reporting there is a significant cost in equipment, in software, in training – particularly in trying to create a safe environment where we feel we can offer our sources the kind of protection that they deserve.”

Rusbridger said The Guardian spent about a million pounds more a year on legal fees than they did five years ago, which reduces the budget to do reporting. “The bills on these things just mount and mount and mount and mount, so you can easily be spending tens or hundreds, hundreds of thousands of pounds trying to get a story into the paper,” he said. “And of course once you get onto secure reporting there is a significant cost in equipment, in software, in training – particularly in trying to create a safe environment where we feel we can offer our sources the kind of protection that they deserve.”

However, in some cases, the biggest chilling effect on investigative journalism based on confidential sources is often not digital exposure of sources, but fear of subsequent consequences such as prison and death.

We’re Being Watched

“I’m more careful with any digital platform that I’m involved in – whether it’s email, phone or any other digital format,” Kuttab, from the Arabic Media Internet Network in Jordan, said. “I assume that [I am] probably being watched, listened to, or read. That’s my starting point and I take it from there.”

Privacy International’s Tomaso Falchetta highlighted the hidden nature of some digital acts that can impact on journalists working with confidential sources.

“Of significant concern is the fact that digital communication surveillance – sometimes by the use of malware on the target’s computer – is usually being conducted in secret so the journalist is not aware of the intrusion and cannot challenge or limit it.”

According to Susan McGregor, deputy director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, a change of practice in managing digital communications is required in response – at both the personal and professional levels.

“It means that we have to be thoughtful about our devices and our communications in the way that most of us aren’t accustomed to doing yet,” McGregor said. “Some of the habits we’ve developed…taking our phone everywhere, always having Wi-Fi on, emailing everything, we’re just going to have to think differently about those things when it comes to work with sources. Chances are we’ll also think differently about them in our personal lives, rather than trying to juggle two frameworks of communication.”

US media lawyer Charles Tobin said there was a growing involvement of legal counsel in the story production process due to source protection issues.

“It’s just becoming more and more acute because you have seen more journalists’ subpoenaed over the last 10 years than you did over the prior 50 years, and so it’s becoming more of the subject of conversation when journalists call for advice,” said Tobin. “You look at issues not only of defamation and the lawfulness of the news gathering, but you also have to have a conversation about protecting the sources and how rigorous that needs to be depending on the journalist’s relationship and promises to the source.

Going Back to Analog

Rusbridger has questioned if investigative journalism based on confidential sources is possible in the digital age, unless journalists go back to basics.

“I know investigative journalism happened before the invention of the phone, so I think maybe literally we’re going back to that age, when the only safe thing is face-to-face contact, brown envelopes, meetings in parks or whatever,” he said.

Catalina Botero, former special rapporteur on Freedom of Expression with the Organization of American States, advised going back to what she called “the classics” of journalism practice.

“Go to the corner, to a coffee shop, and talk to them. This is like a very huge contradiction because you have these great tools, wonderful tools to do journalism all around the world without moving from your house. But at the same time, you need to ensure that no one else is hearing.”

UK QC Millar, who represents several freelance journalists, said that some have a contract phone which they throw into the Thames River at the end of each week. They meet sources in pubs, write notes, and hide the notebooks in distant places in case their houses are searched by police.

Algerian newspaper editor Cherfaoui said journalists in the Middle East and North Africa, in particular, have become very cautious with electronic communications.

“We prefer to meet the person directly and avoid digital platforms,” said Cherfaoui. “Because of mass surveillance and new anti-terrorism laws we like to avoid social networks.”

Simple approaches like stretching the timeline between contact with a source and publication of their leaks have also been used to protect the confidentiality of connections and minimize the chance a confidential source will be identified.

“The more layers you can put between you and the source sometimes is better, and a lot of that is time, said ICIJ’s Ryle. “If someone gives you some really hot information the temptation is to publish that right away, but that’s also when your source is potentially at most risk.”

Taking Responsibility for Security

“Very few journalists use encryption and very few journalists even know how to use it – it’s not in their toolbox and that is a major problem,” Swedish public radio’s Laurin said. “We’re using open-source material that we can change, where we are in control. Because at the end of the day, source protection is our mandate, our job, also under the law, and therefore we cannot use service providers who do not give us the ability to control the information.”

According to ICIJ’s Ryle, another practical consideration is that digital security measures designed to protect sources can be unwieldy and time-consuming, and these factors remain a deterrent to many investigative journalists. The need for simple, cheap technological interventions to protect communications with confidential sources from surveillance was also underlined by an anonymous editor who responded to a survey connected to this study.

Laurin reflected on an investigation where “we needed to investigate the situation on the ground in six different countries and it was impossible for us for safety reasons and also practical reasons. We needed to do our investigations digitally, over the phone, over Skype, over Facebook, email. That was a major challenge to employ all the necessary forms of encryption and secure communication.”

But ICIJ’s Ryle argued that too many journalists are growing unnecessarily paranoid.

“There are some reporters I know who are completely paranoid about their computers – they’re fantastic at encryption, everything is offline. But so what? Most of what they’re working on isn’t relevant.”

Taking “radical” measures to secure communications, including using encryption, can actually risk attracting unnecessary attention, Ryle indicated. “You are sometimes better off hiding in plain view,” he said.

Even providing training in encryption to journalists can attract suspicion, according to Internet Sans Frontiers (ISF) journalist and lawyer Julie Owono.

Training & Editorial Leadership

There is evidence that some news organizations have been slow to respond to the threat of source protection erosion in the digital age, with concerns expressed by several interviewees and survey respondents about the level of understanding among newsroom managers.

Other research also indicates problems with the prioritization of digital security and training by news organizations.

ISF’s Owono told researchers that there has been a significant uptake of digital security training among journalists in Africa and the Arab states since the Tunisian uprising, as reporters have learnt that a single password is not sufficient to provide digital protection.

However, Rana Sabbagh, the executive director of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, said that even the best training cannot keep up with global intelligence services.

“We train our journalists in encryption and how to protect their data, and tell them to always assume that everything you’re doing online, on your computers, is accessible, because even if you give them the best software and training, the intelligence agencies are always a step ahead. They are using the latest technologies to decrypt the content.”

Training Sources

ICIJ’s Ryle acknowledged the problem with digital safety practice among sources.

“Most people who are outed as sources make the mistakes before they come to the journalist,” said Ryle. “And they use their own phone, their own computer, they even use an email address that can be traced back to them.”

Interviewees identified a role for NGOs and professional organizations in the training of sources to communicate more securely in the digital environment, and to support journalists to do the same. For example, the Swedish Union of Journalists recently published a book designed to educate journalists in online source protection called Digitalt Källskydd.

Interviewees identified a role for NGOs and professional organizations in the training of sources to communicate more securely in the digital environment, and to support journalists to do the same. For example, the Swedish Union of Journalists recently published a book designed to educate journalists in online source protection called Digitalt Källskydd.

That level of source education is already happening at The Guardian, albeit in a minor way. A secure electronic dropbox has been launched but Rusbridger said that he doubted that many reporters had successfully gone out and installed PGP22 on a source’s machine and taught them how to use it.

The Washington Post and a number of other major news publishers have also introduced secure dropboxes in recent years. There is also a need for sources to take independent steps to ensure their own digital security.

“Sources have to share the responsibility with us, they have to believe in the cause they’re trying to promote, and it should be a shared responsibility. Both a source, or a whistleblower, and a journalist are aiming for the same thing; expose the wrongdoings and corruption as well as promote good governance,” ARIJ’s Sabbagh said.

Collaborative Strategies

A growing number of regional and international investigative journalism consortia has corresponded with an emerging trend of collective and centralized source protection. In its global investigations that involve myriad international publishing partners, ICIJ essentially becomes the source.

“We don’t take responsibility for the publication of our projects in each country, each organization has to do that, but in terms of giving them the information, we become the source,” said Ryle. “In other words, we give them the documents. ICIJ is the source of the material.”

Offshore: The Guardian‘s Snowden investigation.

Jurisdiction “shopping” also becomes a strategy for some journalistic actors, who seek to base their digital content in countries with a stronger degree of privacy protections than those where the intended audience is based. This was the motivation for The Guardian’s decision to move the Snowden investigation offshore to the US. It is also the reason Bulgaria’s investigative journalism website Bivol is based in France, and a new international Francophone collaboration, Sourcesure, is anchored in Belgium.

Millar QC pointed to another important area of collaboration in source protection – between journalists, freedom of expression activists and people he describes as “good hackers.”

“We’ve done a lot of work with the good hackers in Berlin and in London…we have a stack of wiped laptops in the offices [of the Centre for Investigative Journalism which he chairs], which we sell to investigative journalists at cost price because we’re a charity, having got some of the top hackers in the world to devise defense programs for them and to upload those programs to defend…against back door access to their digital material.”

Yves Eudes, Sourcesure’s cofounder and a journalist at Le Monde, believes that the cross-border, multi-platform collaboration between leading Francophone news organizations is a source of protection for journalists and sources.

Yves Eudes, Sourcesure’s cofounder and a journalist at Le Monde, believes that the cross-border, multi-platform collaboration between leading Francophone news organizations is a source of protection for journalists and sources.

Sourcesure, which is based in Belgium to take advantage of strong source protection laws there, was jointly established in February 2015 by France’s Le Monde, Belgian publications La Libre Belgique and Le Soir de Bruxelle and RTBF (Radio Télévision Belge Francophone).

“Unity is strength,” says Eudes. “This initiative could not have been launched by Le Monde or RTBF alone. Sourcesure is underpinned by a whole spectrum of collaborators, from liberal to conservative media outlets, united by common journalistic values.”

UNESCO’s “Protecting Journalism Sources in the Digital Age” represents a global benchmarking of journalistic source protection in the Digital Age, focusing on developments during 2007-2015. Findings were based on an examination of the legal source protection frameworks in each country, drawing on academic research, online repositories, reportage by news and human rights organizations, more than 130 survey respondents and qualitative interviews with nearly 50 international experts and practitioners.

UNESCO’s “Protecting Journalism Sources in the Digital Age” represents a global benchmarking of journalistic source protection in the Digital Age, focusing on developments during 2007-2015. Findings were based on an examination of the legal source protection frameworks in each country, drawing on academic research, online repositories, reportage by news and human rights organizations, more than 130 survey respondents and qualitative interviews with nearly 50 international experts and practitioners.