Even though an entire generation has grown up with the internet at their fingertips, it’s important to remember that digital journalism is still in its infancy. It has only been 26 years since the world’s first website and server went live at CERN on December 20, 1990.

For context, the Lumiere brothers presented the first motion picture film in 1895. The 50-second film showing a train steamrolling towards the camera was an engineering marvel, but 26 years later the world was just entering the Charlie Chaplin era of motion pictures.

Sound in cinema would take an additional five years, virtual reality headsets another 115.

I began thinking about this longer time frame and the evolution of journalism five years ago when I co-wrote an article in Nieman Reports with Harvard Business School Professor Clayton M. Christensen and HBS fellow James Allworth that applied Christensen’s often-cited theory of disruption to the business of traditional journalism.

From left to right: Clayton Christensen, David Skok and James Allworth

The article, Breaking News, was a look at how traditional journalism had been disrupted by the internet.

I’m thankful that the article has held up well over time but my one regret is that we didn’t consider how digital native journalism, or specifically sites that were born out of the disruption of traditional media, had themselves been disrupted, and what could lie ahead for these digital-only publishers. This article attempts to tackle that question through my own interpretation of disruption theory.

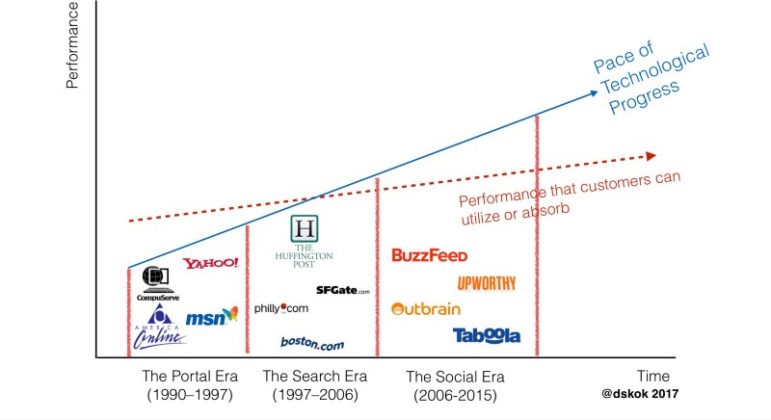

During the first quarter century of the commercial internet, digital journalism has already gone through three eras: the portal years, the search years, and the social years. Each era advanced storytelling and presented new revenue streams, but I would argue that digital journalism is now entering its most exciting period yet.

This period, for the first time in modern history, will be characterized by readers building and improving journalism. Organizations that recognize the opportunity of this new period can realize journalistic independence, produce quality reporting, and build reliable revenue streams, preparing them for whatever the next quarter century may hold.

Before I walk through each era of digital journalism, I’ll provide a brief explanation of the two most relevant Christensen theories that apply: Disruption Theory and Integration vs. Modularity.

Disruption Theory

First, a brief primer on Christensen’s disruption theory excerpted from our 2012 article:

“Disruption theory argues that a consistent pattern repeats itself from industry to industry. New entrants to a field establish a foothold at the low end and move up the value network—eating away at the customer base of incumbents—by using a scalable advantage and typically entering the market with a lower-margin profit formula.

It happened with Japanese automakers: They started with cheap subcompacts that were widely considered a joke. Now they make Lexuses that challenge the best of what Europe can offer.

It happened in the steel industry, where minimills began as a cheap, lower-quality alternative to established integrated mills, then moved their way up, pushing aside the industry’s giants.”

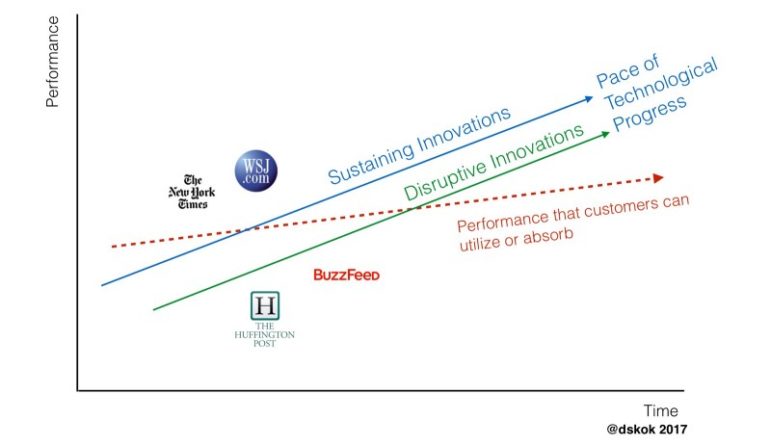

In Breaking News, we argued that newcomers like The Huffington Post and Buzzfeed were disrupting traditional publishers by delivering a product that was faster and more personalized than that provided by the bigger, more established news organizations.

In Breaking News, we argued that newcomers like The Huffington Post and Buzzfeed were disrupting traditional publishers by delivering a product that was faster and more personalized than that provided by the bigger, more established news organizations.

Traditional news organizations used technology to create sustaining innovations that made their products more efficient to produce and consume, such as creating digital newsrooms and products for WSJ.com or NYTimes.com.

New entrants, however, used technology to create disruptive innovations that built new markets for their products.

For example, The Huffington Post built their newsroom for search engine optimization, and later, Buzzfeed did the same to optimize for social media.

Integration vs. Modularity

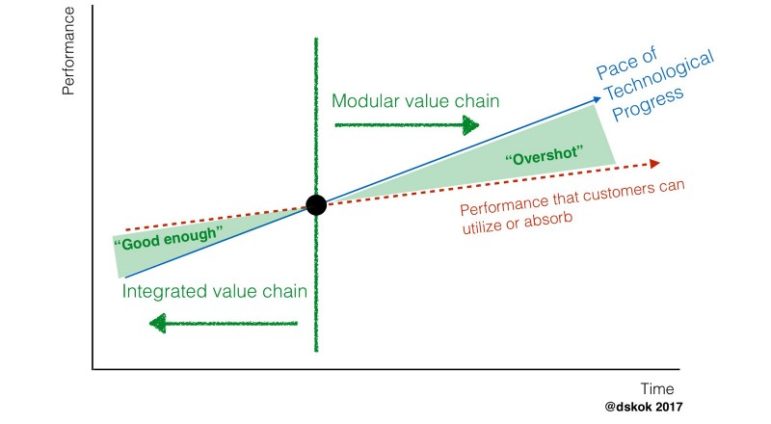

Companies move up the disruption curve in the pursuit of profits. In the early stages of a company’s life cycle, when it’s at the bottom of the disruption curve and just building a new product with new technology, it needs to own its product’s value chain in order for the technology to be good enough for the consumer.

For traditional publishers, for example, owning all aspects of the value chain meant controlling the newsgathering, distribution, and selling of their journalism.

These integrated value chain companies are not yet vulnerable to disruption.

At some point, companies exceed what the consumer really needs from that product. When this happens, a company has “overshot” the needs of its consumers. Meanwhile, improved technology means it is more cost effective for a company to outsource portions of its value chain.

This modular value chain exposes the company to fragmentation, leaving it vulnerable to disruptive competitors who can pick apart different parts of their business.

Each of these cycles of disruption presents perils for some and opportunities for others. When the commercial internet arrived in the form of the World Wide Web, it was perilous for traditional publishers who viewed it only as a sustaining innovation, but an opportunity for those who saw it as a disruptive one.

Enter the online portals.

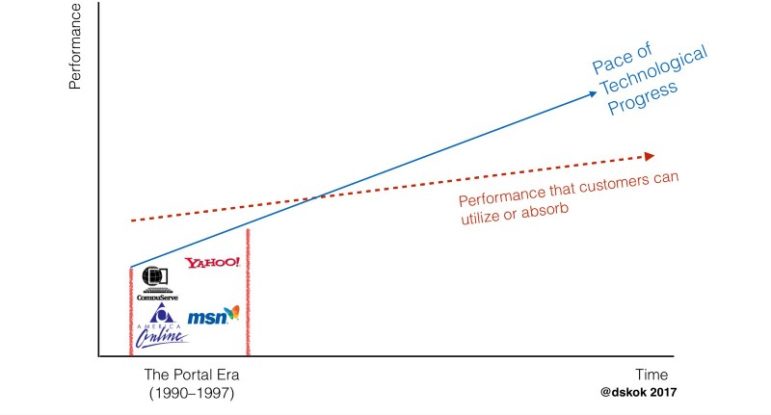

The Portal Era (1990–1997)

The first wave of digital journalism disruptors were the portals. This was a time of integrated value chains, where those owning the bandwidth, software, and the dial-up servers also controlled the digital journalism landscape.

These new entrants included MSN, AOL, and CompuServe, whose revenues were tied directly to their display advertising. If you wanted to advertise next to online news, you needed to buy space on a portal. CPMs were high, inventory was low, and digital advertising ruled the day. These digital platforms closely resembled their print counterparts by being end-to-end publishing businesses who gathered, aggregated, published, and distributed their journalism.

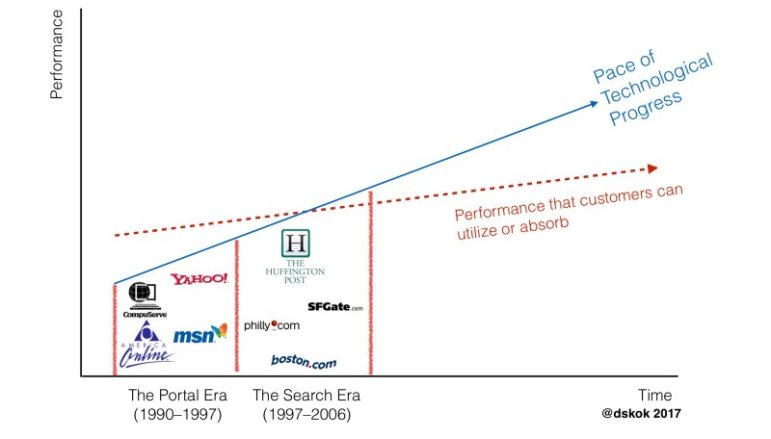

The Search Era (1997–2006)

Second, were the search years. This was a time of discovery and modularity with search engines like Google generating referral traffic to a new set of journalism sites that understood how to optimize for search.

These were sustaining innovations in digital journalism, with The Huffington Post being the most celebrated, and they understood how articles answering questions like, “What time is the Super Bowl?” would drive traffic and ad dollars. By this time, traditional publishers had caught on and so there were also an abundance of free legacy and city-branded sites like sfgate.com and Philly.com that also relied on advertising revenue.

In the early years, CPMs were high and scale was rewarded, but by the end of the era, new advertising technologies like programmatic real-time bidding, put severe downward pressure on the value of CPMs. “Replacing print dollars with digital pennies,” was a common refrain from publishers who recognized that they couldn’t achieve enough scale to replace their traditional revenues through digital advertising alone.

This was a time when digital platforms also began to overshoot the needs of their consumers, resulting in the early days of market fragmentation. Think of unpaid writers, articles written for their headline optimization, pop-up advertising, 75 page photo galleries, article pagination, unmoderated forums and commenting sections, and its not hard to see how customers were no longer being served.

The Social Era (2006–2015)

Next, digital journalism entered its third phase: the social era. During this time the market fragmented even further. Thanks to social networks, particularly Facebook, journalism was optimized for viral buzz and “click-bait” entered common parlance.

It was best exemplified by the rise of Buzzfeed and Upworthy, but also by low-end sponsored content sites like Taboola and Outbrain, all of whom understood that the best way to generate ad revenue was through custom-sponsored advertising and creative campaigns targeting specific audiences, instead of ad impressions at scale.

Digital journalism had now failed to meet the needs of consumers both in content and in user-experience. At the height of the social era, stories were designed for click-ability and impressions, not readability or loyalty.

As digital journalism moved from one era to the next, each site that was born from a respective era accumulated legacy infrastructure and resourcing in advertising technology and workflows that made it more difficult for those sites to respond to the new upstarts born out of the next phase. MSN was able to move from the portal years to the SEO years but they were not able to effectively shift to the social years. AOL was able to make the shift into the SEO years by purchasing The Huffington Post, but couldn’t quite adapt to the social years.

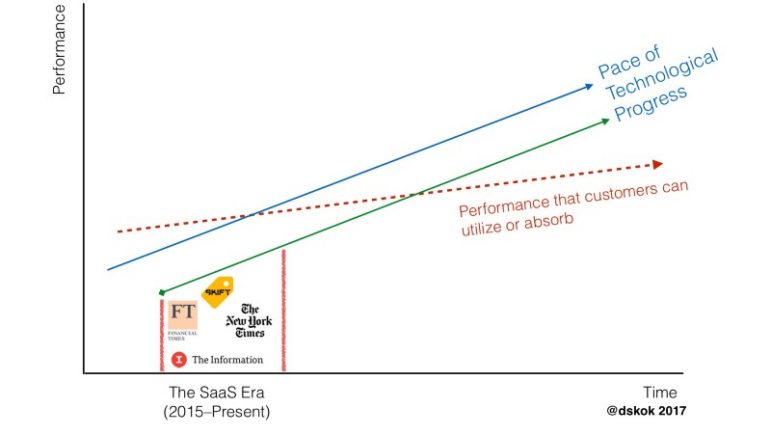

The SaaS Era (2015-Present Day)

That brings us to the present. After twenty years of modularity and accelerated technological progress, where virtually everyone with a blog has the opportunity to become a digital publisher, digital journalism has overshot the needs of its consumers. These consumers are now living through a surplus of news and information, including fake news, that has eroded trust and credibility. They are on a flight towards quality and community. Digital journalism has been commoditized, creating new market opportunities at the bottom of a new disruption curve that is not yet “good enough.”

The technological revolution upending digital journalism and creating this disruptive new market includes the emergence of machine learning, predictive analytics and a targeted understanding of user behavior. These data tools have given organizations that own their entire value chain a leg-up over their competitors. Digital journalism has gone from a modular phase of disruption to a new phase of integration that relies on owning the relationship with your reader through data.

There is a term for organizations that rely on subscription revenues to build and improve their software: SaaS or Software as a Service. This might be a way to define the phase digital journalism is now entering, one that relies on consumers to build and improve the journalism, called SaaS or Stories as a Service.

In part one of this series, I argued that owning the platforms was less important than owning the story. The same principle applies here: Those who own the relationship between the story and the reader will be at a distinct advantage over those who own the production and platforms of newsgathering and distribution.

This journalism era, paid for by readers, for readers, will result in quality journalism, trustworthiness, and the building of new communities. For almost a century, journalism — in all its forms — has been funded by advertisers, and not by consumers. By having readers pay for their own journalism and using the data publishers have to listen to what their readers really want, news organizations can focus on accountability metrics like loyalty, retention, and churn that resemble SaaS instead of a singular focus on CPMs.

Perhaps ironically, this has created an opportunity for traditional publishers to disrupt the earliest digital startups that were born out of the portal and search eras. If print publishers can contain their legacy cost structures and offer a unified editorial vision they could be at a distinct advantage in harnessing their existing subscriber relationships.

An organization that has successfully adapted this approach is the Financial Times. Robin Goad, their head of customer analytics outlined last Spring how the FT had built a formula that accurately predicted whether someone would subscribe or cancel their FT.com subscription. It was only possible for the FT to build the “RFV Formula” as it is now known [Recency x Frequency x Volume] because they owned their customer data.

Consumers have always subscribed to ‘content,’ whether it was a newspaper, magazine, or cable television subscription, but increasingly, as Om Malik outlined in this post, consumers are willing to pay for digital content. Netflix has 93 million subscribers, Spotify 40 million, Apple Music 20 million, Hulu 12 million, and HBO NOW 2 million.

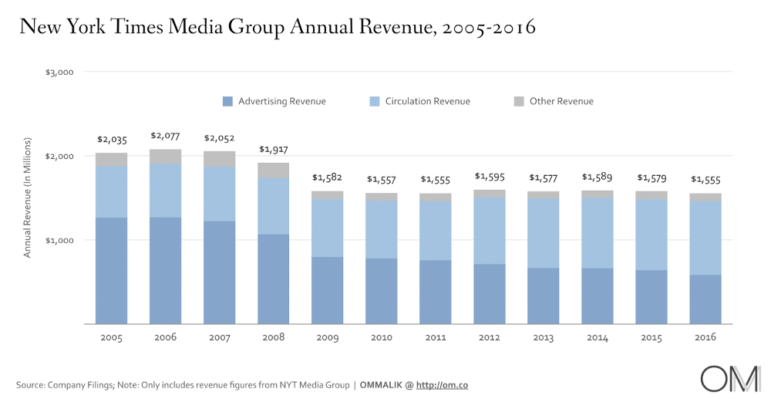

This is true for traditional publishers too. For example, the New York Times and The Financial Times are increasingly replacing their digital advertising revenues with digital subscription revenues.

Most of the publications seeing success with digital subscriptions rely on quality over quantity journalism. It is likely not a mass media but a niche media focus.

For example, Skift — a travel industry publication, and The Information — a tech industry publication, are sites born out of the SaaS era who are focused on doing a few things really well instead of trying to cover their entire world.

Those who will pivot to this new era will have to shed their advertising ambitions that required scale to achieve profitability and instead focus on their subscription ambitions that require focus, engagement and loyalty.

The Next Era?

It’ll take smarter minds than mine to predict the era that will surface next, but no matter what it is, a recurring consumer revenue stream that forces a strong feedback loop with one’s customers, instead of advertisers, will prepare publications to listen, respond, and adapt, in near real-time to the shifting market.

It is an exciting time to be in journalism. Perhaps for the first time ever, it is our readers — not our advertisers — who are determining our fate. The implications of this change trickle down from the boardroom to the newsroom in profoundly positive ways. When you’re assigning stories not for clicks but for loyalty and retention, the journalism and the community will be better for it.

You can read the first post here. The second post here.

This post first appeared on Medium and is reproduced here with permission. David Skok is a digital media executive on the Board of Directors for Online News Association. Formerly with the Toronto Star, Boston Globe and Global News. He was a 2012 Nieman Fellow.

This post first appeared on Medium and is reproduced here with permission. David Skok is a digital media executive on the Board of Directors for Online News Association. Formerly with the Toronto Star, Boston Globe and Global News. He was a 2012 Nieman Fellow.