For Ojo Público, the search for new narratives and formats to tell a story is constant. According to journalists at this Peruvian investigative media site, the method they use is to design investigations that combine revelation and innovation, applying digital tools that allow them to improve reporting and the narrative of their stories, in order to inform the public.

For Ojo Público, the search for new narratives and formats to tell a story is constant. According to journalists at this Peruvian investigative media site, the method they use is to design investigations that combine revelation and innovation, applying digital tools that allow them to improve reporting and the narrative of their stories, in order to inform the public.

“Since Ojo Público was born, we have experimented,” Nelly Luna, a founding journalist of Ojo Público, told the Knight Center. “And we do it because we believe that it is necessary to bet on new formats to reach new audiences and because the digital ecosystem permits investigative journalism, not only to reveal, but to know and approach its audience; it allows you to develop revelatory stories in formats that offer different experiences.”

David Hidalgo, another Peruvian journalist and Ojo Público co-founder, also told the Knight Center that, as a team, they use technological resources to design their journalistic research, and therefore can “prove the finding as conclusively as possible.”

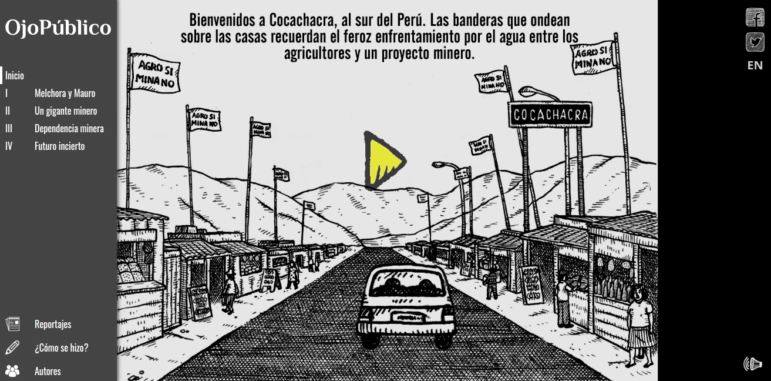

The most recent example of Ojo Público’s constant commitment to innovation in digital narratives is found in the interactive comic “La Guerra por el Agua” (The War Over Water) about one of the most controversial mining conflicts in Peru. In this work, they used a non-traditional narrative format to explain an almost 10-year mining conflict in southern Peru. The inhabitants and farmers of the Tambo valley, in Arequipa, are confronting one of the most important mining companies of the world, Southern Cooper, which is carrying out the Tía María project.

Screenshot of the opening page for Ojo Público’s interactive comic “La Guerra por el Agua”

Composed of 42 scenes and more than 120 drawings, it is the first report developed in an interactive comic format by Ojo Público. It is available in both Spanish and English.

Luna explained that they chose to narrate the nature of this social conflict using the disruptive format of the interactive comic in order to reach new audiences. “Especially the citizens who are not involved in the conflict,” she said.

“We chose a comic for its didactic and narrative power for a complex and urgent issue in Peru: the dispute over water in the face of large mining projects,” Luna explained. “The comic has the ability to portray, from the intimacy of the characters and their realities, stories and details that often go unnoticed in a traditional format.”

The report, that was first conceived of in July 2016, aims to portray the confrontation between farmers in an important valley in southern Peru and Southern Cooper over development of the Tía María project. “The War Over Water” is part of Ojo Público’s investigative series Privilegios Fiscales (Tax Privileges), Luna said.

The series reveals the million-dollar amounts that the Peruvian State fails to receive due to the tax benefits of Peru’s most powerful private sectors, such as mining, according to Luna. For this, Ojo Público prepared and analyzed a database with the financial information in the country from recent decades.

The interactive comic was created and developed by Luna, cartoonist Jesús Cossio, and programmer Jason Martinez.

Prototype of the interactive comic “La Guerra por el Agua” by Ojo Público.

“It was eight months of a lot of learning, trial and error, because none of us three had done a web comic before,” Luna said. “From the outset, it was decided that all team members were involved in the reporting. The three of us traveled to the Tambo valley in Arequipa, the heart of the conflict with the mining project.”

The first chapter of “The War Over Water” was presented in December 2016 in the city of Arequipa, where the mining project is located. Six people have already died in clashes with police during protests.

One of the guests who was invited to present the report was the renowned Maltese journalist and cartoonist Joe Sacco, whose work “Srebrenica” (2014) about the massacre of Bosnian Muslims of 1995, inspired Ojo Público to opt for the format of a comic.

“Comics can tell stories that we do not see in the media,” Sacco said during the presentation of the report.

The entire investigative series Tax Privileges, of which the interactive comic report is part, was financed by Oxfam-Peru, at a total cost of US$18,000.

Visits to the comic book site have exceeded Ojo Público’s expectations, Luna said. In just the second week, it had a readership of 340,000 users and was shared 6,000 times on Facebook.

According to Luna, the comic will be shown in several schools, institutes, and universities in the country, because its narrative has the ability of reaching young audiences.

Innovative Projects

The project “Sworn Statements” from Ojo Público won in the 2015 Data Journalism Awards.

In 2014, Ojo Público created the application Cuentas Juradas (Sworn Statements) so that any user could know the wealth of the mayors of Lima. This application won a 2015 Data Journalism Award from the Global Editors Network.

After that, in 2015, they developed the database Cuidados Intensivos (Intensive Care), which provides information and backgrounds of pharmacists and physicians in Peru.

Building on previous experience, they created Suprema Fortuna (Supreme Fortune), another application that uses data journalism to reveal the personal assets of national judges.

Another of Ojo Público’s investigations, which won the Third Latin American Award for Investigative Journalism in 2016, is Memoria Robada (Stolen Memories). This was the first major regional investigation designed by Ojo Público; it represented an innovative effort to highlight the scale of trafficking in cultural heritage in Latin America and its status as organized crime.

Memoria Robada, a project which Ojo Público collaborated with four other media in Latin America to produce.

It was a collaboration with reporters from various Latin American media outlets like Plaza Pública in Guatemala, La Nación in Costa Rica, Chequeado in Argentina, and Animal Político in Mexico.

Future Projects

As for new formats, Fabiola Torres, also a co-founder of Ojo Público, told the Knight Center that they are exploring news games to tell complex stories.

For this, they have sought the help of video game developers and producers in Lima who have experience in the subject.

“We have two issues related to abuses of corporate power – which is one of Ojo-Público.com’s lines of investigation – that have potential for this format, and it is possible to develop them this year,” Torres said.

The idea of Ojo Público is to enable anyone to experience, through play – in this case, an interactive simulator – the type of abuse that other citizens are subjected to in real life, Hidalgo explained. The game, Hidalgo continued, would show the real dimension of the case in a different way than reading the hard data of a report.

“Unlike other news games, our idea is that we do not necessarily invent a situation, but that the game is as close as possible to real cases investigated by our team,” he said.

Additionally, Hidalgo revealed that they are working on another story in this format that is somewhat more oriented to the political, related to recent cases of corruption in the country.

Workshops and Training Guides

Promoting journalistic excellence and best practices in the trade is another goal of Ojo Público, its cofounder and director Óscar Castilla told the Knight Center.

“In this way, this year we launched OjoLab (@OjoLab in Twitter), Ojo Público’s training, exchange, innovation, and experimentation program that promotes knowledge and skills exchange among journalists, technologists, programmers, designers, and civil society leaders interested in generating urgent and public service stories in innovative formats,” Castilla said.

“In this way, this year we launched OjoLab (@OjoLab in Twitter), Ojo Público’s training, exchange, innovation, and experimentation program that promotes knowledge and skills exchange among journalists, technologists, programmers, designers, and civil society leaders interested in generating urgent and public service stories in innovative formats,” Castilla said.

The OjoLab program includes several training modules ranging from investigative journalism methodology, digital tools, database construction and analysis, NewsApps development, disruptive news formats, fact checking, and journalism business models, Luna added.

The first Lab “Narrate from data” was held between March 13 and 15 in El Salvador and was supported by well-known digital investigative journalism site El Faro. Fifteen journalists from Central America participated, and 10 of them were selected and given scholarships thanks to support from the Dutch organization Hivos, with the collaboration of Accese, an organization that promotes projects on issues related to energy sustainability.

According to Hidalgo, widening knowledge is one of the founding principles of Ojo Público: “That is why we have given investigation or data verification workshops in Peru as well as other countries of the region.”

Fabiola Torres and David Hidalgo presenting the “La Navaja Suiza del Reportero” (The Swiss Army Knife for Journalists).

With that same idea, they launched “La Navaja Suiza del Reportero” (The Swiss Army Knife for Journalists), which, according to Hidalgo, is now used in communication programs in universities in Argentina, Ecuador, and Mexico. They also translated the book, which is digitally available, into English.

Recently, they also launched the digital guide “Por la boca muere el pez” (The Fish Dies By Its Mouth), which promotes fact checking the news. “As in every laboratory of ideas, the sense of success lies in our proposals being incorporated to the best standards of the profession,” Hidalgo said.

Sources of Funding

Regarding the business model of Ojo Público, Castilla explained that it is based on three clearly established sources: financing through international cooperation with organizations that share their editorial line, providing technology implementation services linked to data analysis and visualization, and finally, offering laboratories of investigative and data journalism in Peru and abroad, like the latest development with investigative journalists in El Salvador.

“If we speak in percentages, 70 percent of our income depends, on average, in the first modality, and more than 20 percent in the second source of financing,” Castilla said.

This story, originally posted on Journalism in the Americas’ blog, is part of a special project by the Knight Center made possible through support of the Open Society Foundations. The “Innovative Journalism” series covers digital news media trends and best practices in Latin America and the Caribbean. This story is reproduced here with permission.

Paola Nalvarte is a Peruvian journalist and documentary photographer living in Austin, Texas, who focuses on covering the Andes region. In Peru, Paola worked in the Lima office of Italian news agency ANSA, on the economic news desk of the daily Expreso, and for ten years has worked on various editorial projects doing picture editing and research for one of the world’s oldest Spanish-language papers, Peru’s El Comercio.

Paola Nalvarte is a Peruvian journalist and documentary photographer living in Austin, Texas, who focuses on covering the Andes region. In Peru, Paola worked in the Lima office of Italian news agency ANSA, on the economic news desk of the daily Expreso, and for ten years has worked on various editorial projects doing picture editing and research for one of the world’s oldest Spanish-language papers, Peru’s El Comercio.