The bad news is that long-dominant paradigms of the news business lost effectiveness over the past two decades and are unlikely to bounce back. The fragmentation brought about by the digital revolution is not a reversible process, and the advertising revenue-driven business model, while still valid, will never be quite the same. Moreover, the fallout from the financial crisis (in which we include the electoral victories of Trump and Brexit) saw public trust in mainstream media plunge to historical lows. The Big Media brands still have meaning for many consumers, but competitors like Breitbart.com and Greenpeace.org are legitimizing the alternatives and creating their own networks of information and influence.

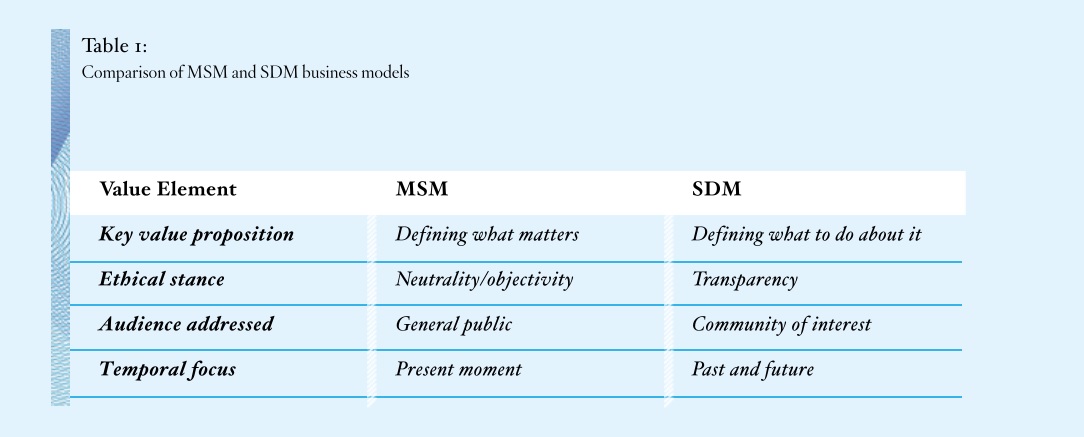

We call these new competitors stakeholder-driven media (SDM), and our recent e-book Power Is Everywhere (available as a free download) describes their ongoing ascendancy and business models. Unlike the mainstream media (MSM), which aspire to provide “all the news that’s fit to print” to a general public, SDM work directly with and on behalf of their audiences to advance the issues, causes, and interests that matter most to them. Instead of telling people what they should care about or need to know to be informed citizens, SDM address publics who already know what matters, and want to do something about it.

We call these new competitors stakeholder-driven media (SDM), and our recent e-book Power Is Everywhere (available as a free download) describes their ongoing ascendancy and business models. Unlike the mainstream media (MSM), which aspire to provide “all the news that’s fit to print” to a general public, SDM work directly with and on behalf of their audiences to advance the issues, causes, and interests that matter most to them. Instead of telling people what they should care about or need to know to be informed citizens, SDM address publics who already know what matters, and want to do something about it.

On one hand, the focus on a community’s concerns means that the potential audience for individual SDM is often smaller than for MSM. (In fact, one of the reasons that objectivity became a news industry standard was to enable publishers to cross partisan lines in building an audience.) But size is not always equivalent to influence, and SDM also exist to exert influence on issues and organizations. Moreover, at a time when many legacy publications and platforms are foundering financially, SDM are proving the business case for an advocacy-based, community audience paradigm.

Let’s be clear: We are speaking not only of militant activism, but also of media that defend communities of practice and interest (such as consumers, different kinds of small businesses, employees in various industries, unions, or followers of various issues or organizations). The advocacy here involves protecting, promoting, and prevailing for and with the audience. That means putting the interests of that community first.

Media sources shared on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. election shows that Breitbart became the center of a distinct right-wing media ecosystem.

It’s not a radical idea; that’s what news media did, and still do, in many places and times. But it does imply that the notion of a “general public” or “mass audience” doesn’t mean what it meant in the early 1990s, before the advent of global broadband internet enabled explosive growth among media outlets and niche audiences, some of which became quite big, like the three million members of Greenpeace. The impact was visible in 2016, when a fragmented universe of alt-right, conservative, and contrarian websites played a key role in mobilizing the Trump electorate. It is false to say that Trump beat “the Media.” One set of media, made of conservative SDM allied with Fox, beat another.

If your publics are no longer general, every component of your news business model must shift to fit that fact. Certainly, we think that there will always be news media that target entire populations, though some have vanished, and others will decline before they stabilize or disappear. Meanwhile, SDM have already integrated the effects of audience fragmentation into their business models.

That starts with the value proposition: If we are no longer neutral reporters, abstaining from judgments and foreswearing ulterior goals, we can still find facts that matter, but we are providing them first to the people who need them most, and are most likely to act on them.

In that case we’re not just providing information. We’re working to shape the world in cooperation with our community, who share our values and mission. What we don’t do – the stuff that they don’t care about, or can get somewhere else – matters as much as what we do. (We don’t do sports, unless we’re a sports community.) We are focused on certain issues, but even more on their outcomes. We want to have an effect on the way the story ends, and we specify the effect. We’re transparent, not objective. We can still pay attention to true facts, and as we’ll show later, we’d be wise to do so.

Let’s consider how this shift worked out at two successful SDM, in two countries, published in two languages. Both of these cases and many others are described in greater detail in Power is Everywhere.

Case Study: Mediapart

The French daily news website Mediapart, launched in 2007, demonstrates that contemporary news consumers will accept a non-neutral editorial stance, on condition that the stance is transparent, matches their own views, and doesn’t affect the reliability of information shared. Mediapart clearly represents the views of a particular community – namely, France’s critical Left, a significant minority of the population. The core of Mediapart’s value proposition to this community resides in muckraking, investigative stories that expose corruption among France’s political and financial elites.

The French daily news website Mediapart, launched in 2007, demonstrates that contemporary news consumers will accept a non-neutral editorial stance, on condition that the stance is transparent, matches their own views, and doesn’t affect the reliability of information shared. Mediapart clearly represents the views of a particular community – namely, France’s critical Left, a significant minority of the population. The core of Mediapart’s value proposition to this community resides in muckraking, investigative stories that expose corruption among France’s political and financial elites.

At its founding, Mediapart’s editorial strategy was to hammer on financial scandals implicating the right-wing party of then-president Nicolas Sarkozy. Co-founder Edwy Plenel, former editor in chief at Le Monde, supported the strategy by raiding Paris’s newsroom for leading investigative reporters, and paid their salaries with the savings in printing and distribution costs inherent to online publication. Put another way, Mediapart built capacity by decimating the competition. Consequently, Mediapart’s investigative abilities distinguish it from the corporate media that dominate the news industry in France, as well as from the relatively independent dailies (Le Monde and Libération) whose downsized capacity increasingly forces them to rely more on style than substance. The rest of the Paris press comments on events. Mediapart drives them.

The strategy paid off when Mediapart turned its attention to the Socialist government that succeeded Sarkozy’s administration. In 2012, the journal broke the news that Minister of the Budget Jérôme Cahuzac had for years held undeclared offshore bank accounts. The following year, Mediapart announced that it had reached the landmark of 100,000 subscribers. Like its closest competitor, the weekly, all-print Canard enchaîné, Mediapart had shown itself to be necessary reading, not only for its first, highly politicized audience base, but also for the elite it covers.

There were other ways that Mediapart created value for its subscribers – the journal’s only source of revenue, as at the Canard. One way was to invest savings from printing and distribution in lowering subscription costs as well. At a price of nine euros monthly, Mediapart is cheaper than the daily and weekly heritage journals it competes with, and provides better insight in both headline and trend stories.

Another way was to create a platform open enough to allow for regular and substantial user-generated content. In particular, Mediapart offered every subscriber the opportunity to publish a blog through its platform. Of course some of those blogs aren’t worth reading. But some of them represent high-level content from actors like former European Parliament deputy and neo-Keynesian economist Liem Hoang-Ngoc, an advisor to Presidential candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon. The editorial staff selects the best blogs daily and promotes them on the home page.

Interactive strategies like this cannot be done very well, if at all, by amateurs, which is why Mediapart’s founders include a web design agency. (The successful Dutch news startup, De Correspondent, likewise shared ownership with its web design agency.) The agency’s input is evident in other value-creating features. We are subscribers, and we can say that it is easier and richer to follow an ongoing story in Mediapart than in any other French journal, thanks to thematic, documentary, and author links. Put another way, Mediapart saves its readers valuable search time on important stories. Not all of its content is as interesting as the watchdog work, but on this key function Mediapart succeeds far better than its competition.

The chief takeaway of Mediapart’s success story is that consumers are ready to pay for good investigative journalism, as long as:

- It cannot be obtained elsewhere for free, and value is added through presentation and access to data (like source documents);

- The price is reasonable and affordable;

- The content defends the users’ point of view – not just in tone, but also in substance. Other viewpoints are not excluded, but neither are they defended. (In fact, they may be ridiculed.);

- The media also provides them with a platform for their own views.

Case Study: Responsible-Investor.com

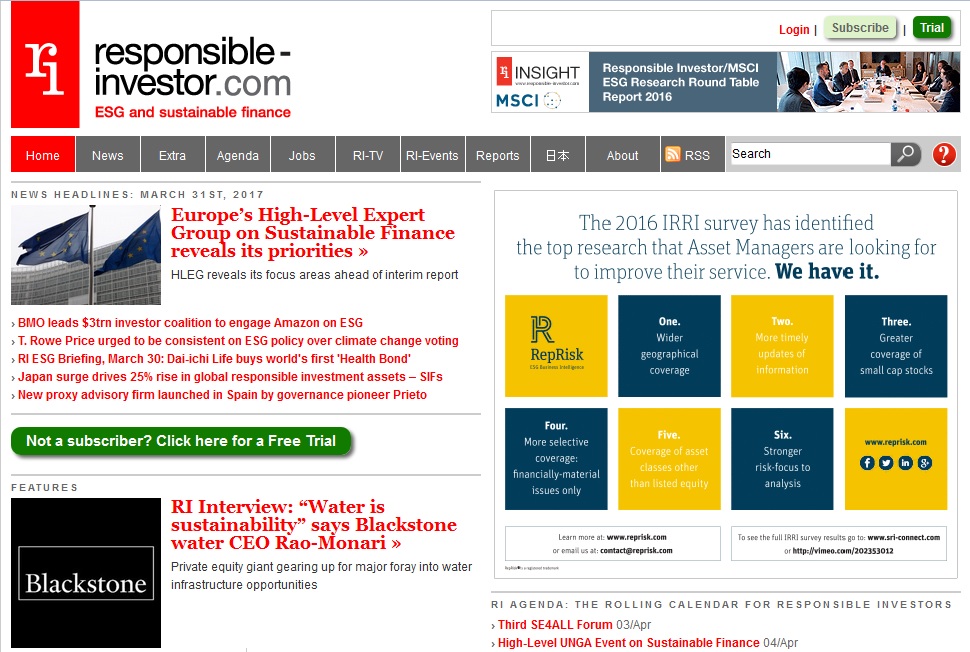

SDM are hardly restricted to the political arena. For instance, Responsible-Investor.com is dedicated to “responsible investing, ESG [environmental, social and governance issues] and sustainable finance for institutional investors” – a growing niche in the corporate world, and also a growing demand among MBA students at business schools like INSEAD. (In fact, ESG studies are becoming a differentiating feature among business schools, a way for them to attract new customer segments.) The site and its readers, in effect, are de facto partners in a common enterprise whose goal is two-fold: Succeed in the securities markets, while helping to take socially responsible investment mainstream. Additionally, Responsible-Investor.com helps police an emerging sector, exposing scams that target its users. Meanwhile, it supplies information that professionals can use to explain and justify what they do to colleagues and bosses. These key services are valuable enough to ensure Responsible-investor a profitable subscriber base.

SDM are hardly restricted to the political arena. For instance, Responsible-Investor.com is dedicated to “responsible investing, ESG [environmental, social and governance issues] and sustainable finance for institutional investors” – a growing niche in the corporate world, and also a growing demand among MBA students at business schools like INSEAD. (In fact, ESG studies are becoming a differentiating feature among business schools, a way for them to attract new customer segments.) The site and its readers, in effect, are de facto partners in a common enterprise whose goal is two-fold: Succeed in the securities markets, while helping to take socially responsible investment mainstream. Additionally, Responsible-Investor.com helps police an emerging sector, exposing scams that target its users. Meanwhile, it supplies information that professionals can use to explain and justify what they do to colleagues and bosses. These key services are valuable enough to ensure Responsible-investor a profitable subscriber base.

The services are leveraged further through a steady series of conferences, which provide attendees with additional information, as well as the opportunity to widen their networks in the field. Co-founder Hugh Wheelan calls the conferences “business development that pays,” because they also drive subscriptions, open new avenues to content and sources, and reinforce the brand.

The services are leveraged further through a steady series of conferences, which provide attendees with additional information, as well as the opportunity to widen their networks in the field. Co-founder Hugh Wheelan calls the conferences “business development that pays,” because they also drive subscriptions, open new avenues to content and sources, and reinforce the brand.

None of it can work, he adds, except on one condition: “The issue is whether you have a decent mission or not.” If the mission doesn’t matter to the target community, and if it isn’t carried out in a reliable and accessible manner, the business model is hollow.

Responsible-investor suggests part of the answer to the threat of fake news. There are publics who can’t afford the luxury of believing in lies or wishful promotions. (You will find others in Power is Everywhere.) The clearest path to success for SDM is to provide those publics with essential facts and insight, whether or not the authors or the audience like their meaning. One of the reasons that The Economist captured the U.S. audience of Business Week is that The Economist foresaw the financial crisis well before 2007, while Business Week, like most of the financial and business press, failed to warn its readers. Looking over the rubble, which watchdog would you feed? The one who barked, or the one who slept while the house caught fire?

The New Value Proposition

Responsible-Investor.com and Mediapart share a strong sense of mission that unites them with their audiences. Subscribers feel they are active contributors to a community that reflects—and works together to promote—their values. Their connection to the content goes far beyond opening a magazine or clicking on a link to an article. They rely on it to act in a turbulent time.

Only a few years ago, the rise of mission-driven SDM was a cause of shock and disdain among MSM managers. SDM were “biased”, or “stupid,” or Internet trash. Both the rise of hard-right populism, supported by SDM like Breitbart.com, and the emergence of investigative journalism among NGOs like Greenpeace, have shattered that condescension. The New York Times has pivoted from the voice of mainstream consensus to the shield of opposition to Trumpism, and become a defender of facts against alternative facts. It is gaining subscribers by doing so.

Only a few years ago, the rise of mission-driven SDM was a cause of shock and disdain among MSM managers. SDM were “biased”, or “stupid,” or Internet trash. Both the rise of hard-right populism, supported by SDM like Breitbart.com, and the emergence of investigative journalism among NGOs like Greenpeace, have shattered that condescension. The New York Times has pivoted from the voice of mainstream consensus to the shield of opposition to Trumpism, and become a defender of facts against alternative facts. It is gaining subscribers by doing so.

This will not be an easy passage for many MSM to negotiate. If they get it wrong, like France’s Le Figaro, which under the ownership of Serge Dassault has become a shrill promoter of the scandal-plagued French Right, they will continue to lose audience, money and influence. (Breitbart.com, too, will stumble if and when its users perceive that it is misleading them.) But if they get it right – if they learn to protect, promote, and prevail for and with their users, without leading them into another disaster like the financial crisis or the Iraq War – they will benefit from the same forces that are building the SDM movement at MSM expense.

It’s not the media business that is dying – let alone the value of real facts – but the perceived value of neutrality. In a not-so-distant past, news media existed to defend their users, as Pete Hamill observed in News is a Verb (1999). They lost their customers’ trust not through an act of God, as Lou Gerstner once told IBM’s people in a time of crisis.

News brands worldwide were launched or bought up by financiers and politicians who used them as instruments, or who downsized their properties’ resource and skill bases to economize on watchdog work. Audiences are telling us that they want their watchdogs back, enough to pay for their services. If you want to succeed in this environment, ask yourself: “Whom do I want to defend? How will I join with them?” The answers are being invented as we write, and more innovations will come.

This post is based on the book Power Is Everywhere: How Stakeholder-Driven Media Build the Future of Watchdog News, which is available for free download.

Mark Lee Hunter is an Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Fellow at INSEAD, and the author of Story-Based Inquiry: A Manual for Investigative Journalists (UNESCO 2009). Luk Van Wassenhove is Professor of Technology and Operations Management and The Henry Ford Chaired Professor of Manufacturing at INSEAD. Maria Besiou is Professor of Humanitarian Logistics at Kühne Logistics University. Benjamin Kessler is Asia Editor & Digital Manager at INSEAD.