In the past decade, open data has grown out of a conceptual discussion into a global movement. While this recent phenomenon largely originated in the West and developed in democratic contexts, China has also been experimenting with various ways of publishing and using open data. Despite its relatively closed internet culture and political environment, there are many areas where open data can bring value to China, especially with regard to government efficiency and effectiveness, data-informed decision-making, and increasing the public’s trust through greater engagement.

In the past decade, open data has grown out of a conceptual discussion into a global movement. While this recent phenomenon largely originated in the West and developed in democratic contexts, China has also been experimenting with various ways of publishing and using open data. Despite its relatively closed internet culture and political environment, there are many areas where open data can bring value to China, especially with regard to government efficiency and effectiveness, data-informed decision-making, and increasing the public’s trust through greater engagement.

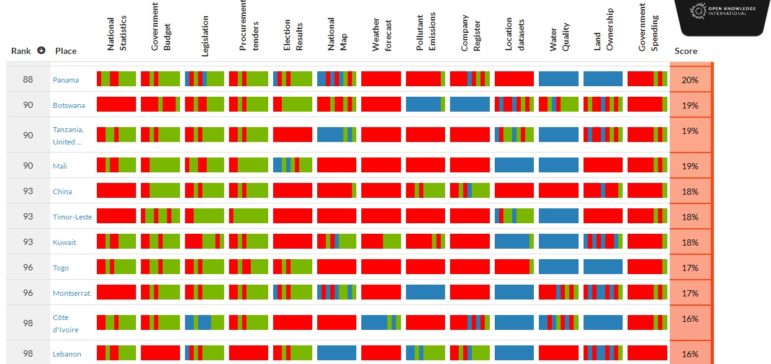

According to the Open Definition, “Open data is data that can be freely used, re-used and redistributed by anyone – subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and share alike.” On the Global Open Data Index, which evaluates the quality and availability of national governments’ open data and provides annual rankings, China was listed number 39 in 2016, up from 93 in 2015, out of 122 countries surveyed.

Global Open Data Index 2015

With the release of the Big Data Development Action Plan by the State Council in September 2015, open data was officially recognized and listed as one of the ten key national projects in the plan. The Plan not only gave a concrete timeline for opening government data, but also explained the motivation behind the national initiative: it is expected that big data and open data may drive economic transition, improve China’s competitiveness and create a modern governance model.

Since 2011, more than a dozen open data portals have been set up, not only in first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, but also local districts in less developed provinces. Different local governments have different approaches: for example, Beijing is more government-led, while Shanghai largely leverages the local universities and civil society. But some of the potential benefits can be universal.

Improving Government Efficiency & Effectiveness

To be able to provide open data to the public, government agencies would need to digitalize their data, publish it in a machine-readable format, and update it in a timely manner. By doing so, they would enhance coordination and communications within the government, especially across departments and agencies. For example, Open Data Amsterdam gave the city’s fire department access to construction information from the water department, which increased service efficiency.

South Reviews report

Such improvement in efficiency is much needed in China, which has a huge and complicated bureaucratic system that hinders collaboration. While still in the beginning stages, there are already examples of open data’s impact in this regard. In Nanhai district of Foshan city, in the Guangdong province in southern China, a Data Coordination Bureau was set up and within one year consolidated data from 65 different departments and agencies of the district government, reported South Reviews in 2015. The data was not only published for public usage, but also served as an indicator for internal reforms to streamline the system. According to China Daily, collected data could reveal overlapping of department functions and duplication of services.

One of the obstacles to breaking the walls between government departments is lack of motivation. However, the “Social Credit System,” since being introduced in 2014, has been a strong driver for data sharing within the government. Social Credit System is a nationwide initiative that aims to build a unified database for monitoring activities of individuals and companies.

By the time the Credit China site, an online portal of social credit for the public, launched in June 2015, it had already aggregated data from 39 participating government departments at the central level. And “persistence in information sharing” remains one of the principles for the initiative, not only across government bodies, but also for civil society and private sectors. Despite international concern that the system would serve as a massive surveillance tool for the regime, it has effectively facilitated data sharing across agencies and sectors with a clear goal and strong technical support.

By the time the Credit China site, an online portal of social credit for the public, launched in June 2015, it had already aggregated data from 39 participating government departments at the central level. And “persistence in information sharing” remains one of the principles for the initiative, not only across government bodies, but also for civil society and private sectors. Despite international concern that the system would serve as a massive surveillance tool for the regime, it has effectively facilitated data sharing across agencies and sectors with a clear goal and strong technical support.

Once all data from different sources are released with the same standard, the interoperability would enable easier consolidation and better analytics, which would lead to more data-informed decisions, both for citizens and the government.

Open Data in Uruguay

In Uruguay, an open data platform of the country’s health services provides comparable information such as waiting times and user ratings, and enables citizens to make informed decisions when choosing healthcare providers. In the UK, tools that are built with open data include TransportAPI, which consolidates transit information such as timetables, routes, live running, and performance history information for a wide range of transport types, enabling citizens to make informed decisions about which mode of travel to use and when. In China, while most of the pioneering cities are still at the phase of collecting and consolidating data, some ideas have already emerged on how open data may have a positive impact.

Take environmental data, for example: China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection has been releasing air pollution data to the public, but not yet according to the open data standard, as the data is not machine-readable. Supplementing the Ministry’s efforts, a few non-profit organizations such as Qingyue have been scraping data and releasing them in a machine-readable format, which made it easier for further re-use and analytics. For instance, the Tongzhou district of Beijing municipality has used Qingyue’s data for its study of the sources of PM2.5, a dangerous particulate matter in smog. The results of such studies would help the government to come up with more targeted solutions to tackle air pollution.

While open data is easy for the public to explore, aggregate, analyze, and re-use, it is also a great tool to build trust between the citizens and the government.

In most democratic countries, where media plays an important role in monitoring authorities and keeping the government accountable, data journalism can be very impactful in situations where data may be used to unveil problems. In China, however, this role is weaker as most media outlets are under strict censorship and propaganda control. The strict control of media reporting minimized the potential risk for the government. As a result, the data journalists in the country mostly work on less sensitive topics such as economy or lifestyle, and are more likely to use data requested from other sources than open data.

However, open data is still a great opportunity for citizen engagement, especially in the form of open competitions. The Shanghai Open Data Innovation Challenge in 2016 attracted more than 3,000 participants to explore the 1,000 gigabytes of data released by the municipal government and to develop apps and services with the data. The finalists were invited to present their proposals to the government and provided with resources to implement their ideas. By giving access to the government’s data, creativity and talent amongst the public are mobilized, and communications between the citizens and the government are strengthened, with trust likely increased.

While there are several success stories of experimenting with open data in China, many challenges still lie ahead, such as the absence of clear guidance and strong enforcement, the lack of transparency culture in the government, weak data literacy among both officials and the public, and limited tracking of data usage and impact. To fully realize the potential benefits of open data described above, the Chinese government needs to draft practical guidance for data release, promote open culture within the system, and hire talents with technical capacity and data knowledge. Otherwise, China may lose the opportunity of practicing data governance and leveraging data economy, which would be a shame in the age of data.

This post first appeared on the website of the Global Policy Journal and is cross-posted here with permission.

Yolanda Jinxin Ma is a consultant with expertise on social innovation, ICT for development, and data journalism. She is currently a fellow of Global Governance Futures 2027. Most recently she worked at the United Nations Development Programme on innovation, communications, and technology.

Yolanda Jinxin Ma is a consultant with expertise on social innovation, ICT for development, and data journalism. She is currently a fellow of Global Governance Futures 2027. Most recently she worked at the United Nations Development Programme on innovation, communications, and technology.