Shell knew all along.

Shell knew all along.

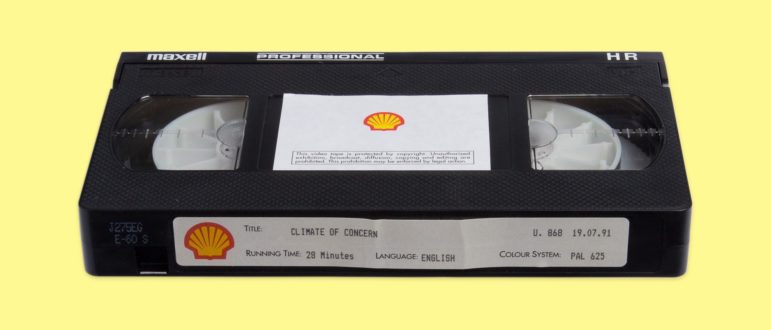

A 1991 videotape obtained by our Energy and Climate Correspondent reveals that Shell had detailed knowledge of the dangers of climate change more than a quarter of a century ago. Confidential Shell documents date back even further.

How did we get those documents?

A reader shared them with us.

At our Dutch journalism platform De Correspondent, we’ve learned that joining forces with readers leads to richer, more grounded stories. Better yet: It leads to scoops that we would never have found on our own.

Our latest investigative piece — published together with The Guardian — is a great example of that.

We’d like to share our experiences from the Netherlands, in the hope they might help or inspire you in your own journalism endeavors.

It started with a call-out to readers: https://t.co/CRflv4QArm And look what that call-out produced: https://t.co/ylUPx43Rtv

— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) February 28, 2017

Here’s what we’ve learned about reader engagement in the Netherlands:

Our 55,000 paying members know more than our 21 full-time correspondents. We try to involve them as much as possible in our reporting, so they get the chance to share their knowledge and experience.

Here’s our workflow for correspondents:

- Share your story idea or main question before you get started. Correspondents first announce what they want to figure out and why they think their new topic matters.

- Invite readers to share their knowledge and experience. Correspondents ask for specific input and check to see if they’re missing anything. Expert members then join the conversation.

- Share your learning curve. Dutch journalist Joris Luyendijk coined this phrase when he wrote his Banking Blog at the Guardian. He arrived in the City of London as a journalist — decidedly not a financial expert — and wanted to publicly document his journey to figuring out how our financial system works. We took on that approach, and we’ve found that being open about the new things you’re learning as a journalist makes your reporting more accessible for readers and encourages readers in turn to share their knowledge with you.

This is how we used the workflow for the Shell story:

1. The original call to readers

Jelmer Mommers

Jelmer Mommers is our Energy and Climate Correspondent. His journalistic mission is to show the impact of climate change and, together with members, to speed up the transition to sustainability.

With his topic, Jelmer can’t ignore Big Oil. If giants like Royal Dutch Shell and its subsidiaries around the globe keep pumping and guzzling fossil fuels, the earth’s climate will be damaged beyond repair.

But instead of just talking about people at Shell, he wanted to talk with them. And not just with company spokespeople.

So Jelmer published a call to readers: “Dear Shell employees, let’s talk.”

He wrote:

“CEO Ben van Beurden said in Shell’s company magazine that “there is a now a mistaken belief among some people that climate change can be solved in a very simple way. Those who understand the energy system know it can’t.” Do you know something outsiders don’t? Do you think society — and journalists like me — misunderstand what’s required for making the transition to clean energy? If so, email me and we’ll set up a meeting.”

2. Sharing the learning curve

Dozens of people who work or used to work for Shell reached out to him. Jelmer interviewed 19 people from Shell and got to know the company better with each talk.

Dozens of people who work or used to work for Shell reached out to him. Jelmer interviewed 19 people from Shell and got to know the company better with each talk.

He started publishing transcripts of these interviews–the Shell Dialogues–and writing his own analyses to convey his lessons learned.

He noted down the most frequently heard criticism from Shell employees of his research, how they soothed their conscience, and documented change processes within the enormous company.

3. Becoming an insider

We discovered that sharing your learning curve has a flywheel effect. The updates Jelmer published amplified his reach and trust. They brought in new readers and new sources.

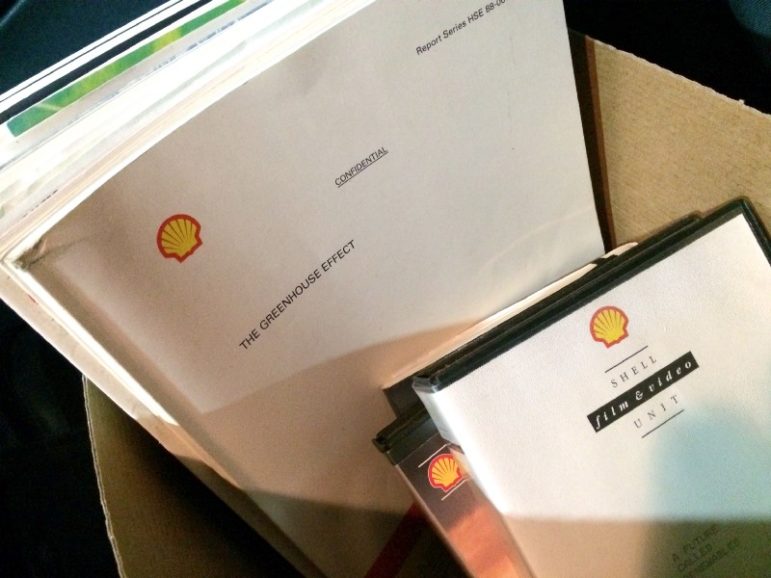

One of them was responsible for what Jelmer calls “the most romantic moment” of his journalism career: the moment this person handed him a box full of internal documents.

In the box, Jelmer found an internal study written by Shell employees on the greenhouse effect. The 1986 report noted the significant uncertainties in climate science at the time but warned of the possibility of “fast and dramatic” changes that “would impact on the human environment, future living standards, and food supplies, and could have major social, economic, and political consequences.”

In the box, Jelmer found an internal study written by Shell employees on the greenhouse effect. The 1986 report noted the significant uncertainties in climate science at the time but warned of the possibility of “fast and dramatic” changes that “would impact on the human environment, future living standards, and food supplies, and could have major social, economic, and political consequences.”

By that time Jelmer had also obtained a video from 1991 — fifteen years before Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth — titled Climate of Concern. This Shell film clearly laid out how fossil fuel burning was warming the world and that serious consequences could well result.

By that time Jelmer had also obtained a video from 1991 — fifteen years before Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth — titled Climate of Concern. This Shell film clearly laid out how fossil fuel burning was warming the world and that serious consequences could well result.

So Shell knew.

But the oil giant continued to invest in fossil fuels and undermine ambitious climate action. Even today, less than 1% of its investments go to sustainable energy sources and climate friendly techniques.

Why?

During his conversations with Shell employees and other experts, Jelmer gained more and more understanding of why the company had done very little.

It helped him uncover all the ways in which Shell frustrated climate legislation to safeguard its business, while internally admitting to the grave dangers global warming was posing to humanity.

That’s a contradiction Jelmer could never have described in such detail, had he remained an outsider.

4. Setting up international partnerships

This is obviously not just a national story. That’s why our international editor Maaike Goslinga helped Jelmer set up partnerships with outlets from other countries.

Maaike is always looking for more effective ways our correspondents can collaborate with foreign journalists. Because topics that transcend national boundaries — like the earth’s climate — deserve to be looked at from a global perspective.

Jelmer teamed up with the Guardian’s Environment Editor Damian Carrington, who conducted additional research and covered the story for his outlet. The Danish daily newspaper Information partnered with us too, and devoted a five-page spread to the story.

5. Publishing the story in different forms

We want to adapt our publication to our readers’ various preferences.

Basically, Jelmer provides four different entry points to his research:

A public notebook, aimed at insiders who have expertise on the topic or want to keep track of all updates Jelmer writes during the research process.

A public notebook, aimed at insiders who have expertise on the topic or want to keep track of all updates Jelmer writes during the research process.- An extensive reconstruction, for those who want to know what Jelmer’s most important findings and conclusions are.

- A short news story, for readers who have little time and just want to be briefed on key facts.

- The full Shell movie, as well as a clip of highlights.

Impact

At De Correspondent, we try to redefine the concept of news. We don’t parrot whatever grabs the most attention, we aim for original work that provides the most insight. Our correspondents write about the most relevant developments rather than speculating about the latest scare or breaking news. Our journalism works to uncover the underlying forces that shape our world.

This sometimes leads to discussions with other journalists. Here’s Jelmer, on how the press responded:

“A few journalists from traditional news organizations kept asking: Where’s the scandal? Did Shell cover the film up? No. Were they as evil as Exxon in spreading lies? No. Did they do nothing at all to better themselves? No. So what’s the story?”

The story is structural, Jelmer replied: “It’s the fact that a company with such in-depth knowledge about an issue — Shell management was told in 1996 that climate change was “potentially the most serious and intractable environmental issue faced by mankind” — has shown itself incapable of true transformation, while at the same time vehemently defending its existing business and developing new innovative ways to extract ever more oil and gas, the very fuels they knew would wreck the world’s climate.”

“My reconstruction shows in detail how even an oil company that explicitly expressed to the world that action was needed, was structurally unable to change. That’s not news in the traditional sense, but I believe it’s interesting journalism. It sheds light on the shortcomings of our institutions and it clearly shows the need for more radical change to the structures that determine our future.”

As author and environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote in an op-ed for De Correspondent:

“For those who want to believe in the basic goodness of human nature and human institutions, the last few months have been rough. Any operating system that spits out Donald Trump as an answer has been badly corrupted. But Trump is a snapshot, a moment — a glitch, perhaps. Backing up to get a longer view can be even more devastating. I fear that’s the way to think about the newly uncovered Shell video.”

We were glad to see how the foundational instead of the sensational became headline news all over the world:

Virtually every important Dutch news outlet brought the news. As did the Guardian, The Huffington Post, Wired, Mother Jones, Observador (Portugal), Newsweek Europe (UK), Information, Politiken (Denmark), La Vanguardia and El País (Spain).

Late in the evening, Shell’s former CEO responded to the attention Jelmer’s story generated. Jelmer will continue his research on Shell. Sign up to our free weekly newsletter to receive his latest articles.

Experiences from the Netherlands

We’re currently conducting the Netherlands’ largest group interview with refugees. We asked our readers to pair up with a refugee who applied for asylum here in the past year. The pairs meet monthly and readers interview the newcomers one-on-one to find out what life is like for them in their new country — something that’s often ignored by the mainstream media. Since last September, over 300 readers succeeded in finding refugees willing to open up to them about their lives.

Perhaps another big story will come from this reader-powered research.

We hope that our experiences in the Netherlands can help you with your journalism endeavors.

This post was originally published on Medium and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

Ernst-Jan Pfauth is co-founder and publisher of De Correspondent, an ad-free, member-funded Dutch journalism platform for constructive journalism. Ernst is the former Head of Digital at NRC Handelsblad, former editor-in-chief of tech news site The Next Web, and is an author of two books on blogging.

Ernst-Jan Pfauth is co-founder and publisher of De Correspondent, an ad-free, member-funded Dutch journalism platform for constructive journalism. Ernst is the former Head of Digital at NRC Handelsblad, former editor-in-chief of tech news site The Next Web, and is an author of two books on blogging.