This edition presents a collection of great journalism that might serve as a source of inspiration to find original stories, to innovate in how to tell them, or to find a thread to develop a fresh angle. This is a list of winning stories and individuals drawn from 16 major global or regional journalism awards given in 2016.

The stories deal with six broad topics, which also reflect some of the main problems societies are facing. Many examine the plight of migrants: from the unofficial detention camps of African migrants in Tripoli, to the ordeal of a family fleeing from ISIS-controlled territory to Germany.

Other articles deal with abuses of security forces and state officials in different countries, from the killing of protesters in Xinjiang (China), to a massacre of civilians in Apatzingán (Mexico) by police, and how cadres of the Egyptian security forces are abused by their superiors. Many of the acclaimed pieces refer to ongoing social struggles, like those of the ghost-like second and third children of Chinese families who could not be registered and have been denied entry to school by their parents during the official one-child policy; or the tragedy of people with albinism who are killed by superstitious neighbours in Mozambique.

Other articles deal with abuses of security forces and state officials in different countries, from the killing of protesters in Xinjiang (China), to a massacre of civilians in Apatzingán (Mexico) by police, and how cadres of the Egyptian security forces are abused by their superiors. Many of the acclaimed pieces refer to ongoing social struggles, like those of the ghost-like second and third children of Chinese families who could not be registered and have been denied entry to school by their parents during the official one-child policy; or the tragedy of people with albinism who are killed by superstitious neighbours in Mozambique.

There are a few stories of war: one about young men in Portugal joining a violent extremist religious group, another of a family trying to survive in Syria. Finally, there are many stories about corruption. These include an exposé of deputies in the Jordanian parliament who won public tenders worth millions of dollars in return for government passing specific laws, or shady negotiations for young soccer players in Nigeria, or abusive financial practices that made some churches in Zimbabwe very rich.

A review of the awards also shows that producing good journalism does not come easy. Some documentaries took months to produce, like the one that tells the story of the environmental damage and human suffering caused by the building of a huge dam in the Brazilian Amazon jungle.

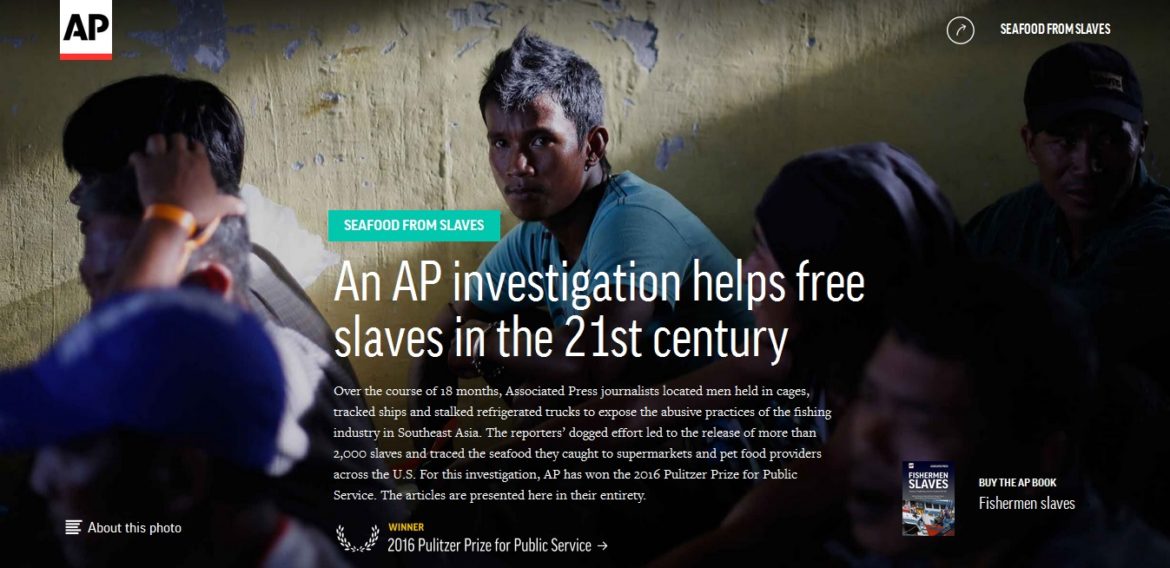

There were also investigative pieces that involved dangerous reporting, like the twice-acclaimed (Pulitzer and Hong Kong’s Human Rights Press Awards) AP story on slave-like conditions for workers in the seafood industry in South East Asia that supplies supermarkets and restaurants in the United States. Many of these reports required months of preparatory work to set up digital platforms that could enable not only the mining of information in millions of documents, like ICIJ’s Panama Papers, but also the simultaneous collaboration of hundreds of reporters.

There were also investigative pieces that involved dangerous reporting, like the twice-acclaimed (Pulitzer and Hong Kong’s Human Rights Press Awards) AP story on slave-like conditions for workers in the seafood industry in South East Asia that supplies supermarkets and restaurants in the United States. Many of these reports required months of preparatory work to set up digital platforms that could enable not only the mining of information in millions of documents, like ICIJ’s Panama Papers, but also the simultaneous collaboration of hundreds of reporters.

Often reported under duress and published with the fear of retaliation, these stories illustrate how journalism grows when the environment turns bleak, as happens today even in countries where freedom of expression has been taken for granted. In quiet or more peaceful times, some media players can grow too close to power, too patronizing of anyone who is not a part of their inner circle. Then, when self-proclaimed anti-establishment presidents rise, they can easily fabricate the media as their enemy, and thus, try to destroy the legitimacy of journalists.

As these stories remind us, journalism does not thrive through privileged access to the corridors of power or on the comfy cushions in presidential palaces. Journalism blossoms in the trenches, where people need megaphones to voice their pain and their pride; this is where the great stories are cooked. It is through the painstaking search for documents and the posing of uncomfortable questions that journalism derives its legitimacy.

Another outstanding finding of this review of 2016’s international journalism prizes is the fact that of the 77 media outlets whose reporters received awards, 32 were outlets or projects created in the last five to seven years; the vast majority was produced by small teams with meagre resources but plenty of passion. A few are not even media, but civic ventures like the Marshall Project, whose reporter won a Pulitzer together with a journalist from ProPublica, for exposing the failures of the United States’ law enforcement agencies to investigate reports of rape; or the Spanish Civio Foundation, with its data journalism site Medicamentalia, that investigated the gaps in access to 14 essential drugs in 61 countries.

Three stories published in traditional mainstream media were actually done by freelance reporters. Of the 12 journalists decorated for their outstanding or courageous careers, eight of them are either freelancers or work for small digital outlets.

This should be revealing to more seasoned media outlets now facing new challenges in the United States and Europe. Quality journalism does not necessarily go together with big newsrooms and thick budgets.

Small interdisciplinary teams can produce the best stories and compete head-to-head with big news agencies or established media houses. The voice of one single reporter can stand out through the quality of his or her reports, as much as that of a whole media house.

In sum, journalism can better resist the attacks of the popular, twitter-prone, or wannabe dictator-presidents, and remain genuine to the eyes of an increasingly critical public, when it sticks to the kind of reporting celebrated in these awards.

This story originally appeared in the February 2017 newsletter of the Open Society Foundation’s Program on Independent Journalism and is reprinted with permission.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.