David Leigh in Rio at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2013.

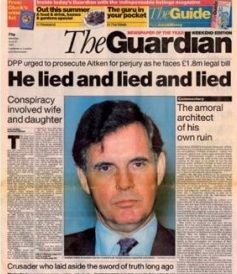

David Leigh is an award-winning British investigative journalist and author and the former investigative editor at The Guardian. A longtime member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Lee’s 1995 documentary film Jonathan of Arabia, exposed the links between Jonathan Aitken, then a British Cabinet Minister, and arms being sold to Saudi Arabia. Aitken refuted the charges but was later charged with perjury.

In 2010, Leigh was a member of the team which handled the release of United States diplomatic and military documents which had been passed to WikiLeaks, and which worked closely with Julian Assange. Leigh retired from The Guardian in 2013 and now works as a consultant. He also teaches investigative journalism at City, University of London.

Hetq caught up with Leigh who was in Armenia for the Tvapatum Investigation: Media Against Corruption journalism conference on December 6-8. He spoke about cross-border journalism cooperation.

What was your favorite investigative story?

My favorite story was the one that was most frightening for me. I made a film about a British government minister who was the Minister for Arm Sales, and he had a corrupt relationship with Saudi-Arabia. He was doing arms deals of his own on the side. We made a film about it, and he sued us for libel. He called a press conference and called me terrible names. He said I was the “cancer of a bent and twisted journalism”, and he was going to overthrow me with the sword of truth. And then he launched a very big libel case.

We very nearly lost it in the middle of the trial, I remember. I couldn’t sleep, I woke my wife up at three in the morning and I said you’ve got to understand we’re going to lose this case and I will never work again, so you’ll have go and find a job.

And then, at the last minute, we found some documents in the basement of a Swiss hotel that had gone bankrupt and had closed down. It was all about who paid his hotel bill, and he said that his wife had paid it. But these documents proved that his wife couldn’t have done it because she was in Switzerland at the time. So, it was proof and we went to the court, waved these papers, and the case collapsed. And he went to jail for perjury, for telling lies. That’s the only time I’ve ever put a minister in jail, and he nearly finished me off.

And then, at the last minute, we found some documents in the basement of a Swiss hotel that had gone bankrupt and had closed down. It was all about who paid his hotel bill, and he said that his wife had paid it. But these documents proved that his wife couldn’t have done it because she was in Switzerland at the time. So, it was proof and we went to the court, waved these papers, and the case collapsed. And he went to jail for perjury, for telling lies. That’s the only time I’ve ever put a minister in jail, and he nearly finished me off.

Weren’t you confident when you had all the documents to publish the story?

In those days, the libel law in Britain was much stricter than it is now. It has been reformed. But at the time it was very easy to sue people because you had to prove that everything was true. And now the law in Britain has been relaxed. You have a defense if you can show that what you did was in the public interest, and that you took care and you behaved responsibly. And if all those things are so, then you don’t have to prove to a legal standard that everything you say is true. So, it’s made life easier now, but in those days life was dangerous for journalists in Britain.

What’s the average time you spent on each investigative story?

It’s impossible to say. Some stories you can do in a week or even a day. One of the things that we did at The Guardian that I was quite proud of was that we managed to prove that BAE — the big arms company, was selling their planes by bribing everybody all over the world with the collusion of the British government. To get to the point, we proved it and the story to come that became a national scandal, took about seven years. And I don’t mean that every day for seven years we would work on the story. We would find a bit of the story, we’d publish it, and then somebody would come to us and say here’s more, or you published that, somebody else, you know, has done an investigation.

It’s impossible to say. Some stories you can do in a week or even a day. One of the things that we did at The Guardian that I was quite proud of was that we managed to prove that BAE — the big arms company, was selling their planes by bribing everybody all over the world with the collusion of the British government. To get to the point, we proved it and the story to come that became a national scandal, took about seven years. And I don’t mean that every day for seven years we would work on the story. We would find a bit of the story, we’d publish it, and then somebody would come to us and say here’s more, or you published that, somebody else, you know, has done an investigation.

One of the good things about working for newspapers, rather than television, is you can keep on publishing stories, and every time we published something it stimulated somebody to come forward. You keep writing stories that stimulate, people read them and they say: “Oh, you know, I’ve got something to say about that.” And if you’re lucky, it stimulates new sources.

The climax of it was when a police investigation started. The British prime-minister blocked the investigation because he said it was bad for Britain’s national security. And at that point, after seven years, being ignored by everybody, the story certainly took off, because everybody else then had something to write about and it was a big scandal. And that really took seven years from the first time we decided to try and expose what was going on.

What are the risks for investigative journalists in Europe and especially in Britain?

I said in the conference that the risk for a journalist like me in Western Europe is not normally to be attacked or to be killed or put in prison. The risk is being sued, and lawsuits are so expensive to defend, and they are very distracting. When I got involved in this libel case I talked to you about, it really took like two years of my life, I was thinking of nothing else but how to defend this case. Sometimes, bad people know that they can distract journalists by suing them, involving them in law cases, because then it diverts them, and then they think about defending themselves.

And I think that’s a very big problem because the way journalism is developing now, as you know, conventional newspapers certainly in Western Europe and America, their business model is disappearing, and in part the job of investigative journalism is being taken up by small organizations that work online or that are non-profit, supported by donors. The problem with small organizations like that is that one big lawsuit can destroy them, it can make them bankrupt. I have seen this happen as well.

So where does the confidence of being protected come from?

One of the things that has made life better in Britain is that we have got a reform of the law so there is more protection for journalists who do what we do, behaving in the public interest, behave for the public good. Apart from that, I was involved in setting up a small non-profit organization in Britain called the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and what I advised from the beginning was that whatever they did with a big story that they found they should partner with a big media organization, like a big newspaper or a big TV company because they would carry the legal risks. Not only do they have more resources, but they could carry the legal risks, so that a small investigative outlet would not be the publisher. They would be the partner of the publisher.

Are big media companies interested in these kinds of stories?

They have learnt to be interested because they are running out of money. And if somebody comes to light and says we have a story, we’ve got some money from donors, that we’ve researched it, and here is a story that you don’t have to pay for, they’ll be very grateful.

How can small organizations solve their funding problem?

You have to find donors. There are philanthropists out there who will put up money. This organization I talked about — the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, is supported by a number of donors, rich people. And in America there are now quite a lot of them — ProPublica, for example. It’s got its own problems, because journalism driven by donors is also a problem. One thing — they only want you to do journalism about things they are interested in. In America, ICIJ had a problem some years ago, because the donors who were willing to give money wanted them to write about the tobacco companies. If they wanted to investigate the tobacco companies, they could investigate them all the time, because there was always money for that. But there wasn’t money for other things, because donors weren’t so interested. So, that’s a problem. It is very difficult to get money for investigative journalism.

Does this also mean that the independence of journalism, and especially investigative journalism, is at risk?

Yes, it is at risk. But then it’s at risk for many things. It’s at risk from proprietors, from owners… There were many times in British newspapers where the interest of the owner of the paper and the interest of the journalists have clashed. I mean there are many dangers in trying to be an independent journalist.

Have you worked in teams and how important is it for investigative stories?

I have always liked working in small teams. When I ran investigations for a Sunday paper called The Observer in Britain, and then ran them in The Guardian, in both times the core team were just two people — me and another reporter. And then, if we had a big project, we would get other people to join in, maybe freelancers or maybe people from other departments of the paper. And then, after the story was over, everybody would disperse.

I think it is a mistake to set up big departments of investigative journalists, to recruit people and say: “Right, you know, you six people are going to be investigative unit”. Because then, you sit around and think what should we investigate. I think it is the wrong way around. I think it should be story-led. You should start with the story. Somebody comes in, it’s a scandal that they want to expose or it’s some information they prepared to reveal. You look at the story and say — what does this story need? Who does it need? You build your team around your story, not the other way around.

What can cooperation between journalists and readers look like? What can the readers do? There was a project that The Guardian did involving people in the study of documents on the expenses of MPs.

Well, I’ve got to tell you, I don’t think that was a very good idea.

Why?

It did not produce any valuable result. And I think it’s a very nice idea to involve readers, but in practice, when you’re doing investigations, it doesn’t work because it is a specialized activity and it needs expert knowledge. And what that case that you’re talking about demonstrated was that the readers couldn’t really help.

Mr. Leigh, it’s a long time you been in investigative journalism. What changes have you seen over the years and what changes do you predict, also considering the new digital tools that are the basis for many stories?

Because I am very old (smiles), every single skill that I learnt as a young journalist when I started, has become obsolete. Like I learnt to work a typewriter. Now, my students don’t know what a typewriter is. I learnt to make telephone calls from a telephone box in the street. Nobody does that any more cause they all have mobile phones. And, of course, the whole business of print is becoming obsolete. This is taking longer than we thought. So now I have to completely rethink all the time what I’m doing.

I’ll give you an example. When we did WikiLeaks, which was five or six years ago, we got all this material and we searched and said we’ve got a story. Every single incident from the war in Afghanistan, for example, is chronicled here with exactly what happened – where and when the bombs went off and how many people were killed, how many injuries and so on.

I’ll give you an example. When we did WikiLeaks, which was five or six years ago, we got all this material and we searched and said we’ve got a story. Every single incident from the war in Afghanistan, for example, is chronicled here with exactly what happened – where and when the bombs went off and how many people were killed, how many injuries and so on.

My superiors at The Guardian said: “What you need is a data visualizer, and here is our data visualizer.” And a man appeared who was The Guardian’s data visualizer. I didn’t know that there was such a job. And he proceeded to take all these data and turned it into a moving map that moves through time and shows every single day throughout the war: the explosions, where they went off, how they worked, etc. It was like a little sort of animated graph, and I was amazed, I didn’t know you could do this kind of thing. And it takes quite a lot of resources to do it.

Every year, I have to learn something new. And of course, all the journalists that I teach now must be able to do video. They have to work online. We say that to publish an investigation is no longer good enough to just publish it in print. You have to have multiple points of access. People have to be able to read it, they have to be able to see a video, they have to have the graphs, they have to have the pictures, they have to have hyperlinks so they can click through to the original documents or related articles. Everything is now a big construction, a big package, which is a lot more work.

The famous Danish physicist Niels Bohr said (it was a joke really): “It is very difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” That’s what I think about the future of journalism. Ten years ago, we thought that there would be no more print newspapers in five years. Five years came and went. One or two newspapers have stopped printing and they’ve gone online. Most of them are still printing. Many of them still have big problems. The Guardian has very big financial problems. So maybe five years from now they will stop printing, maybe they will go online.

And there are all these other online rivals now — Buzzfeed, VICE News, Huffington Post… But again, it’s difficult to tell whether they will survive or not. And the whole way that people consume information now is altering so dramatically, it’s frighteningly hard to predict. If anybody could predict it, they would be very rich person. I’m quite glad that I’m now virtually retired, because I think it is very difficult and dangerous to be a young journalist now, because you don’t know whether there is any way you can work.

What is the core thing that is always the same in journalism?

Lord Northcliffe, who was a British newspaper owner, once said: “News is something that somebody, somewhere, wants to suppress, and all the rest is advertising.” That’s my slogan, I think of that a lot. Everything else is advertising unless somebody wants to stop it.

Mr. Leigh, you are also a professor at the City University of London. What do you advise your students when they first enter your class, and is there an advice you would give to journalism students in Armenia?

I teach a course in investigative journalism; it’s a postgraduate course. There are about 23-24 students every year, and when they arrive, I say to them: “Don’t think that when you leave this course, you will go to an employer with the certificate and say I am an investigative journalist and hope they give you a job.” Because they won’t, they’ll just laugh at you. You have to say “I have been taught how to do research and I can do research and I know how to research things accurately.” So, I hope some of them will get work. I say the patient accumulation of facts is important.

This post first appeared on the website of Hetq Online and is cross-posted here with permission.

Hetq Online has been published in Yerevan, Armenia, since 2001, and is available in Armenian and English. The site, run by GIJN member Investigative Journalists of Armenia, has become one of the leading sources of independent news in Armenia.

Hetq Online has been published in Yerevan, Armenia, since 2001, and is available in Armenian and English. The site, run by GIJN member Investigative Journalists of Armenia, has become one of the leading sources of independent news in Armenia.