On a savagely hot day in August 2004, a group of Arab and Danish journalists sat around a fountain in the courtyard of an ancient Damascus house, sipping fresh lemonade to quench their thirst.

On a savagely hot day in August 2004, a group of Arab and Danish journalists sat around a fountain in the courtyard of an ancient Damascus house, sipping fresh lemonade to quench their thirst.

They had no inkling of the war, the killing, or the turmoil that would engulf their region in the years to come.

But they had a project in mind that they hoped could bring peaceful change: a Danish-funded investigative reporting program for the Arab world that would boost accountability, free speech, and independent media. A bold attempt to bring water to a thirsty land.

After screening a few names they settled on “ARIJ” — an acronym for Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism but also an Arabic name meaning “the beautiful scent of a flower.”

Two months later, they had their first board meeting in Amman. ARIJ, they agreed, would work in stages to promote the culture of investigative reporting in Arab newsrooms and media faculties by disseminating new skill sets.

It would also assist journalists in focusing on issues of public concern, prioritizing democracy and the rule of law. But they would move carefully. In countries with severe press restrictions, they would confine their digging to “safe” topics like health, education, consumer issues, women’s rights, and the environment.

Thanks to funding from the Danish parliament, ARIJ would train, coach, bankroll, and assist with pre-publication legal screening to try to mitigate the risks. There would be benchmarks for excellence.

The board hired an executive director to run the project in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, three neighboring countries with very different political and media environments, before expanding to other Arab states. For a while, change – positive change – seemed attainable.

In Jordan and Syria, the rulers had succeeded their fathers and promised reforms. New, privately-owned media were mushrooming in an atmosphere of greater openness.

Out of a one-room office in Amman, Jordan, ARIJ started to lay roots across the region. By 2008 it had expanded to Egypt, followed by Bahrain, Iraq, Palestine, Yemen, and Tunisia.

Today ARIJ celebrates its 10th anniversary in nine Arab states. In the next few years, it intends to expand still further, working with individual journalists and local investigative networks.

Joining a global team: Arab journalists played a key role in exposing those behind The Panama Papers.

But already its core achievement has been to help spearhead the emergence of investigative journalism in a region with no such tradition. Since it began formal operations in early 2006, it has trained over 1869 reporters, media professors, and students. Around 400 hard-hitting reports uncovering wrongdoing through investigative techniques have been broadcast or published in local, regional, and international media. Most have sparked reforms, sometimes immediately.

After one ARIJ-sponsored story, Jordan’s King Abdullah ordered a ministerial committee to strengthen the rights of mentally-ill children in line with international standards and to end their abuse at the hands of care givers behind closed doors.

In Tunisia, it took two years for the government to start closing kindergartens that were preparing children to become Jihadis – but only after a high-risk investigation involving an undercover female reporter with a hidden camera, strapped to her body.

For the first time, seven leading Arab universities are now teaching ARIJ’s three-hour credit course on the basics of investigative journalism and at least 20 others are using the manual “Story-Based Inquiry.” Both were compiled by Mark Lee Hunter, a Paris-based award-winning investigative journalist, now a media professor at INSEAD. Since its publication by UNESCO in 2009, “Story-Based Inquiry” has been translated into 12 languages — and that is not the only way in which ARIJ is influencing international practice.

For the last two years ARIJ’s MENA Research and Data Desk has assisted dozens of Arab and international journalists in uncovering fraud in the region and beyond. It played a crucial role in the global network of investigative reporters, mining the “Panama Papers,” the largest cross-border investigation to date.

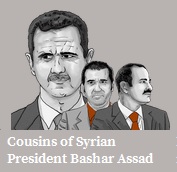

At least 10 Arab journalists, mostly publishing under aliases and in foreign media, exposed a network of offshore companies and bank accounts linked to Arab strongmen and their business partners. One reporter revealed how Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and his allies have been able to avoid international sanctions by registering shell companies in safe havens like the Seychelles. Another detailed the fortunes of senior Yemeni officials and businessmen.

This was the first time that Arab – not Western – journalists, had gone after Arab dictators and uncovered their financial dealings. An important precedent.

With the help of IT experts and an EU fund, the ARIJ Desk is now putting together a database of corporate records, government tenders, and land deeds from 18 Arab states. It has collected and preserved data from government websites, many of which have since been erased and hopes soon to unveil what may be the most comprehensive, searchable database of public records in the Arab world. Every month, ARIJ researchers get an average of 18 requests for assistance from Arab and international journalists.

These achievements are bright spots in the otherwise impenetrable darkness surrounding the Arab media, where press freedom has been in free-fall for the last five years.

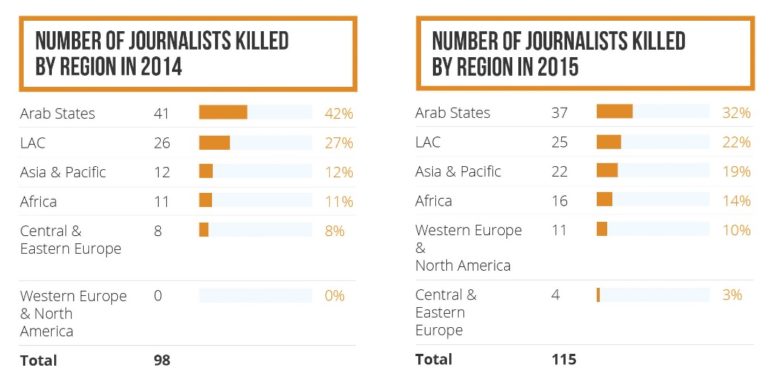

Across the region, the task of investigating and holding officials accountable is getting more complicated and dangerous, journalists are being jailed and killed, censors are clamping down on independent reporting.

After China, Egypt has become the world’s second largest jailer of journalists. Extremist groups are also targeting the press. Last year, ISIS men caught a Syrian freelance journalist filming inside one of their schools. His cameraman was interrogated and a week later his throat was slit on camera.

In spring, Mostafa Marsafawi, an ARIJ-sponsored journalist who documented cases of death, torture, and abuse by officers of Egypt’s Central Security Forces, was fired from his job.

The BBC, which screened the televised investigation, was heavily attacked by at least four pro-government talk show hosts. And so was ARIJ. The hashtag #BBC#plots against Egypt trended for a day.

But journalists have more to worry about than just the government. Those who risk life and liberty often encounter a shocking lack of public support. At every turn they see ordinary Arabs give up on basic freedoms and democratic rights for nothing more than vague promises of stability and economic prosperity.

They see people more afraid of chaos than of “normal” Arab repression. They see people who have accepted the limitations of dictatorship and made their peace with it.

Hardly surprising, therefore, that free and independent journalism has become a low priority.

So what is to be done? Should Arab investigators give up on an unsupportive society and wait for better times? Many insist they’ve come too far to turn back. And yet the cost of continuing their work is daunting.

New anti-terror laws introduced by Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, along with internet restrictions, have dealt a severe blow to investigative reporting. As a result, the state narrative dominates the public sphere and officials easily escape accountability.

On top of that come the economic realities that are complicating the journalist’s life. Investigative reporting has never been a profitable business, especially when it relies on the support of governments or non-profit foundations. But now the funds are dwindling and costs are on the rise.

On top of that come the economic realities that are complicating the journalist’s life. Investigative reporting has never been a profitable business, especially when it relies on the support of governments or non-profit foundations. But now the funds are dwindling and costs are on the rise.

Donors have new priorities, not least a global and intensifying refugee crisis and de-radicalization. The world now needs to find a home and support for 60 million displaced people, fleeing conflict and economic hardship. Sooner or later we journalists have to learn to sustain ourselves.

I should remind you, though, that free speech and honest reporting should not simply become optional extras on anyone’s balance sheet. They are indispensable ingredients in a democratic society – vital safeguards against dictatorship, tyranny, and lawlessness.

We fought to initiate them in this region. We fight to maintain them. We don’t intend to give them up now.

In that spirit, the ninth Annual Forum of Arab Investigative Journalists opens on Dec 1, 2016, at the Dead Sea, the lowest point on earth. More than 350 Arab journalists, editors, and media professors will debate growing censorship across the region along with rising disinformation. Meeting under the theme “ARIJ; a decade of investigating the Arab world; hearing, seeing and exposing,” they will learn new skills to encrypt their software and files, physical protection, and digital narration.

A lot is expected of them. They need – and deserve your support.

This story first appeared on the website of GIJN member Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) and is reproduced with the author’s permission. ARIJ’s ninth Annual Forum of Arab Investigative Journalists is this weekend.

Rana Sabbagh is executive director of ARIJ. She has dedicated more than three decades of her career as journalist, columnist, and media trainer to promote free speech, independent media, “accountability journalism,” and human rights. ARIJ is the region’s leading not-for.profit organization spreading a culture of investigative journalism inside nine Arab states.

Rana Sabbagh is executive director of ARIJ. She has dedicated more than three decades of her career as journalist, columnist, and media trainer to promote free speech, independent media, “accountability journalism,” and human rights. ARIJ is the region’s leading not-for.profit organization spreading a culture of investigative journalism inside nine Arab states.