Successful digital media: producing good journalism — and a conversation around it.

Many great actors failed to adapt from silent movies to the “talkies” and disappeared from the big screen. By the same token, many great journalists risk fading away because they are not adjusting from the era of virtually silent audiences to the virtual era of talking audiences.

This explains why in many countries, digital journalistic enterprises launched when social media was already mature rapidly run ahead of legacy newspapers, even those that made big cash injections into their digital operations. Of course, successful digital media must produce good journalism, but their true secret is creating a conversation around it. They are open to their public and easily let them know who they are.

In one example in Eastern Europe, despite the traditional formality of many East European media, a new digital outlet had no problem sending a video to their audience of the editor sitting in her kitchen apologizing for a boring newsletter they had sent. In Latin America, new digital outlets have also successfully broken with the formal, ceremonial tone so characteristic of serious media there. Reporters tell the stories behind their best stories; introduce themselves with slang, as if to friends; constantly correct their mistakes; and when they have a conflict of interest about an issue, are candid about it. They let their public know that the media is only human.

In one example in Eastern Europe, despite the traditional formality of many East European media, a new digital outlet had no problem sending a video to their audience of the editor sitting in her kitchen apologizing for a boring newsletter they had sent. In Latin America, new digital outlets have also successfully broken with the formal, ceremonial tone so characteristic of serious media there. Reporters tell the stories behind their best stories; introduce themselves with slang, as if to friends; constantly correct their mistakes; and when they have a conflict of interest about an issue, are candid about it. They let their public know that the media is only human.

These journalists offer their audiences a new, more transparent, and freer horizontal culture. However, sometimes, even those passionate journalists forget it takes two to tango. They want to tell their readers a lot about themselves, but do not care to listen. Recently I saw journalists from Central America and the Middle East marvel at how little they knew about their readers after taking an intensive “read your analytics” course. They said that knowing their Google stats and monitoring their following on social media makes a big difference to knowing how their stories are received.

But they, along with other media, including the largest US newspapers, have been realizing that tracking graphs and trends is not the same as talking with your public. (“We can count the world’s best-informed and most influential people among our readers”, said the New York Time’s 2014 innovation report. “Yet we haven’t cracked the code for engaging with them in a way that makes our report richer.”)

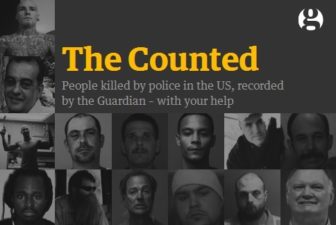

Media in digital era know now they should invite readers to discover the world with them: open doors so that their audience can check the public discourse with them (like many of the 100+ fact-checking outlets around the globe are doing today); know the experts among their readers so that they bring insight into their news; call upon those with a generous heart to help them go through the millions of documents they just got from a source and build a database; ask the furious and the bullies, who write insults under their articles, where does their anger come from and, listen; open a space to let readers decide which reportage they should do; invite first-hand witnesses to document a problem they are investigating… the list of how much they can enrich their journalism is endless.

Media in digital era know now they should invite readers to discover the world with them: open doors so that their audience can check the public discourse with them (like many of the 100+ fact-checking outlets around the globe are doing today); know the experts among their readers so that they bring insight into their news; call upon those with a generous heart to help them go through the millions of documents they just got from a source and build a database; ask the furious and the bullies, who write insults under their articles, where does their anger come from and, listen; open a space to let readers decide which reportage they should do; invite first-hand witnesses to document a problem they are investigating… the list of how much they can enrich their journalism is endless.

For those journalists with blinders who believe that engagement with audience is the business of marketers, Monica Guzman in her great guide about audience engagement published this year with the American Press Institute proves them wrong. It is not about delivering a product, it is about making sure your readers know you respect and value them, she says, “showing them that together, they have important things to teach each other.”

Around the world independent journalism becomes stronger on the shoulders of the communities they serve. Eldiario in Spain and Mada Masr in Egypt define themselves as a culture, a way of being, a clique, an idea of the society they want to be. And they build this dream together with a community that feels invited to be part of their world, well-treated, partaker, equal, like in any really good conversation. The “talky” public is here to stay and those journalists who fail to see their luck in this new era are likely to fade away.

Tools to Communicate with Your Audience

For example, Ask is a tool developed by the Coral Project, a joint effort by the Mozilla Foundation, The New York Times and the Washington Post, sponsored by the Knight Foundation, to “collect, support and share practices, tools and studies to improve communities on the web”, which also creates open-source software to help journalistic enterprises of all sizes and types communicate better with their audiences.

For example, Ask is a tool developed by the Coral Project, a joint effort by the Mozilla Foundation, The New York Times and the Washington Post, sponsored by the Knight Foundation, to “collect, support and share practices, tools and studies to improve communities on the web”, which also creates open-source software to help journalistic enterprises of all sizes and types communicate better with their audiences.

Ask, like Hearken, is a more sophisticated version of the better known Google Forms or Typeforms. But in one way or another they will allow you to ask whatever you need to know from your audience and allow them to upload their contributions.

Inviting Readers To Share

LA Times explains its methodology on crowdsourcing information from migrant student protestors who took to the streets of California a decade ago. From archive photos reporters created a video to invite participants to get in touch and share their stories on what had changed in their lives since that historic moment. They used Screendoor to reach students from 50 different schools.

LA Times explains its methodology on crowdsourcing information from migrant student protestors who took to the streets of California a decade ago. From archive photos reporters created a video to invite participants to get in touch and share their stories on what had changed in their lives since that historic moment. They used Screendoor to reach students from 50 different schools.

Screendoor helps media outlets to organize daily tasks better and crowdsource their journalism. It provides tools to gather and analyse information from readers and tell stories bringing in collective knowledge of the audience.

Watching Trends and Curating Content

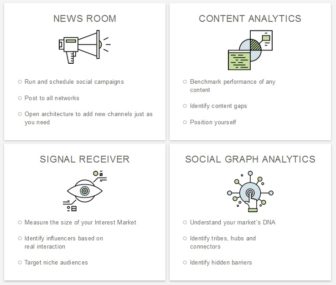

To know your audience one should ask questions and listen to the answers. Liquid Newsroom works on identifying trending topics and breaking news threads on social media. It also offers a tool to visualize social media followers in a graph and identify whose opinion is most influential.

To know your audience one should ask questions and listen to the answers. Liquid Newsroom works on identifying trending topics and breaking news threads on social media. It also offers a tool to visualize social media followers in a graph and identify whose opinion is most influential.

Instead of relying on social media imposed algorithms, Piqd, a German startup, has chosen to give back reviewing and curating power to its readers. Journalists, politicians and other field experts are invited to pick the most interesting piece they read elsewhere during the day and add their short review. Piqd wants to become “a social network for content exchange” getting its value from interested readers community.

This story originally appeared in the August 2016 newsletter of the Open Society Foundation’s Program on Independent Journalism and is reprinted with permission.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.