In part one of this blog I discussed the need for journalists to save evidence they find online and some of the techniques for recording that information. In part two, I’ll focus on some of the issues journalists face when it comes to saving information from social media and mobile devices.

In part one of this blog I discussed the need for journalists to save evidence they find online and some of the techniques for recording that information. In part two, I’ll focus on some of the issues journalists face when it comes to saving information from social media and mobile devices.

How, for example, can you record exchanges that take place on WhatsApp or Skype? How do you capture a live medium like Twitter?

Even before you save any information from a social network that requires you to log in, you may want to consider protecting your own privacy. Imagine you wrote an article about the social media activity of a violent extremist group and illustrated it with a screen grab from Facebook. If you’d logged in under your private login, your user name and possibly the names of some of your friends and colleagues may be visible on the screen shot. Before you use any such image, check that any compromising details have been obscured.

Saving Information from Facebook

When a story breaks and you need to investigate the person who will be grabbing the headlines, it’s important to get in early. Social networks are notorious for removing controversial content.

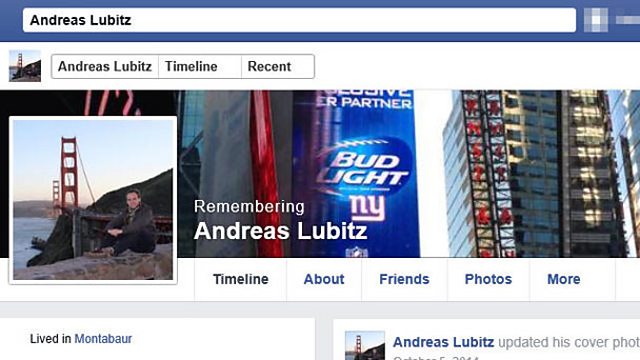

When German pilot Andreas Lubitz deliberately flew a plane full of passengers into the Alps, his Facebook account had been deleted even before his name had been released. I suspect this was at the request of the police. Luckily a basic version of the page existed in Google’s cache and it provided us with a low resolution copy of his profile picture.

That’s all we had until the page reappeared. The family of a Facebook member who’s died can apply to have their account preserved as a ‘memorialised’ page. In this case, that gave us a brief window to grab more details, before the page was eventually taken down for good.

During that window I saved his timeline, the pages he liked, the photos he had posted and, since his friends list was private, a list of the people who clicked ‘like’ on his photos.

Andreas Lubitz’s memorialised Facebook page with my Facebook user name pixelated to avoid identification.

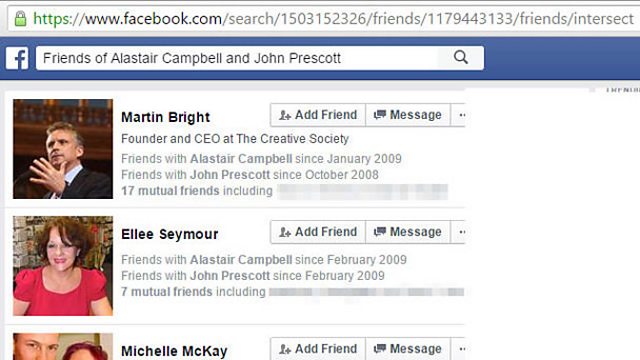

Facebook can be searched and manipulated into providing a wealth of information beyond what is normally provided on a user’s account. You can, for example, find a list of people who ‘like’ a company you are investigating. You can find mutual friends of two Facebook members. You can find their mutual ‘likes’. You can trace the movements of an individual, find the comments they have left on others’ posts, the photos they like etc. Once you have conducted your search, save the results page for later reference. A previous article outlines how to carry out such enhanced searches.

An advanced Facebook Graph search for mutual friends of John Prescott and Alastair Campbell.

Beware of the ‘Filter Bubble’

The above example highlights a problem of using your personal Facebook account to conduct research. The Facebook search has skewed the search results by putting the accounts it thinks are of most interest to me at the top of the list. It assesses this by looking at my interests, friends and likes. This personalising of search results is often referred to as a ‘filter bubble’ and can be an unwanted feature. Most researchers prefer search results to be ordered by relevance rather than any personal connections. To avoid this, search Facebook using a blank, generic account with no friends and no likes.

Check that Saved Pages Work

Whenever you save a page from the internet, it’s a good idea to open it up immediately to check that it saved correctly. Some saved Facebook pages have failed to render properly when opened and older versions of Internet Explorer had a nasty habit of saving the wrong Facebook page. If you have problems with saved pages, try switching to a different browser.

It’s always best to save a webpage as an HTML file (by holding down control + S). However, if the worst comes to the worst, Google Chrome will allow you to save a web page as a PDF document. You can do this by typing control +P (as if you were printing the page), then choose PDF as the destination.

Google Chrome allows you to save web pages as PDF files. Formatting may not be perfect, but at least the links are preserved.

Use Third Party Websites To Save Twitter Information

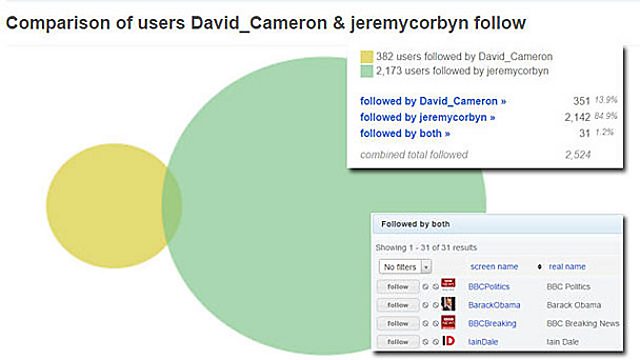

Many third party websites display content from social networks in imaginative, useful formats. Followerwonk, for example, lets you compare the followers and people followed by two Twitter accounts. This might be easier than saving two sets of follower lists.

Use third party websites to save Twitter information Many third party websites display content from social networks in imaginative, useful formats. Followerwonk, for example, lets you compare the followers and people followed by two Twitter accounts. This might be easier than saving two sets of follower lists.

If you just need a record of every tweet sent by a Twitter user, All My Tweets will list them on a single page. Of course, it might also be a good idea to take a copy of the original social media accounts for evidence reasons and because this is usually the most familiar way of illustrating a story.

All of my tweets displayed on one page using All My Tweets.

Scroll to the Bottom Before You Save

When saving a page from a social media account like Twitter or Facebook, make sure that all the required content has loaded, before saving. A friends or followers list will often keep growing as you scroll down. Keep scrolling until all the names have loaded – then save.

Saving From Mobile Devices and Their Apps

Most mobile devices and their apps are a little unfriendly for anyone wishing to save evidence. At the moment, an iPhone will not allow you to capture video from the screen. Instagram won’t let you zoom or save images. Capturing a WhatsApp conversation can be cumbersome and the images are rather small if captured on an old iPhone.

Don’t despair. More modern devices capture larger images, so ideally use a new iPhone for your screen shot. Modern iPads produce even larger images.

Some apps – Instagram, for example – have a web version. There are also third party apps and web pages that make it easier to use and save evidence from Instagram. There is also a lot of cross-posting of images between social media accounts, so an image on a mobile-only app might have exposure on a different social network site’s web page.

Many apps have software versions for computers. I was recently surprised to learn that the secure messaging app Telegram can be run on a PC, making it easier to grab evidence and communicate securely. It might be tricky to capture your Skype conversation on your mobile device, but it’s easy to use a screen-recording programme if you switch to your PC.

App design and features vary enormously across the different platforms. If you find it difficult to save information on an iPhone, for instance, try switching to an Android device.

Finally, remember that social media content – like other material you can find online – may be subject to copyright restrictions.

This post was first published by the BBC Academy and is reproduced here with its kind permission. You can find part one of this series here.

Paul Myers is the BBC College of Journalism‘s Internet Research Specialist, where he helps TV & radio programs conduct investigations that involve trickier aspects of online research. He also hosts regular training courses. Blending his previous career as a computer programmer with journalism, Paul pioneered many online research techniques now widely used. You can find more of his work at Research Clinic.