Hundreds of what appear to be Twitter bots are artificially inflating the retweet and favorite counts of tweets with links to articles from some of Russia’s top news agencies. Lawrence Alexander discovered that these same fake accounts have previously mass-posted links to scores of pro-Kremlin LiveJournal blogs—themselves part of a network of thousands. In this piece, which originally appeared on Global Voices, Alexander walks us through his research process.

Why are suspicious Twitter accounts mass-retweeting stories from top Russian news agencies? Images mixed by Tetyana Lokot.

My research for this article began when I spotted an unusual trend among the Twitter accounts of Russia’s larger news outlets. Among the Twitter users retweeting and favoriting stories from the likes of RT, RIA Novosti, and LifeNews, many had timelines that consisted almost entirely of retweets.

Suspicious Account Behavior

Typical examples of retweet-heavy user accounts include MarishaSergeeva,

MilenaRuineva, KlaraUkralaKolu, olga04p, laraz1377, and babichevaSonya

[archive: 1 2 3 4 5 6].

Upon closer examination of the accounts’ metadata, it became immediately obvious they had all the hallmarks of fake accounts: their bios were either short and sketchy, featuring bland slogans, or were left completely blank; their avatars all had the appearance of stock images posed by models or were unrelated images from cartoons.

Their behavior differed from that of the bots featured in my first article for RuNet Echo, which didn’t retweet or favorite, and followed each other in a closed network. Analysis of a collection of these newly-identified accounts with NodeXL failed to reveal any similar community clusters.

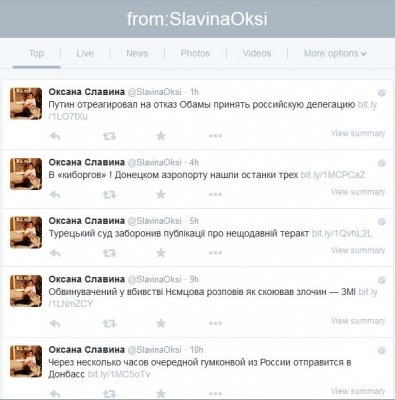

Whilst some accounts were entirely dedicated to retweets, others (such as SlavinaOksi) also posted a number of links to news stories.

The vast majority of links tweeted by “Slavina” lead to stories on kievsmi.net, one of the pro-Kremlin “news” sites (in this case, created to look like Ukrainian media outlets) in the web network previously covered on RuNet Echo.

At this stage, it became clear that some Russian-language media organisations were likely having their Twitter popularity artificially inflated by accounts that looked and acted suspiciously non-human. But on what scale was this happening, and was this phenomenon unique to the Russian Internet or representative of a wider online trend?

Comparing the Trends

To get a clearer answer, I wrote a basic Python script to search the timelines of the recent retweeters of a selected Twitter account and identify the percentage of retweeting accounts whose last thirty tweets were all retweets (marking them as suspicious). Certainly, such a simple measure had the potential to produce false positives from regular users who habitually retweet. But the results it returned were both interesting and surprising.

Over the course of nearly two weeks, I gathered data from the Twitter accounts of media agencies in Russia, Ukraine, the UK, and the US, producing an average score based on the number of retweets they received from suspicious accounts.

For baseline comparison of normal Twitter behavior, I employed a random sample of 45 Twitter accounts in English and 45 in Russian. These were gathered by searching for any users tweeting the conjunction ‘and’ in each language.

For my pool of media-related Twitter accounts, the English average score (for retweets by accounts that were marked as suspicious) was 18.6%, with the RuNet scoring only slightly higher at an average of 20.3%.

Consistently, Russian-language news outlets showed more retweets from bot-like accounts than their English counterparts.

The graph below shows the average rating for each news agency’s account over a two-week period:

The top scores came from @emaidan_ua, @novostikiev and @kievsmi—all of which are linked to the pro-Kremlin website network. The accounts of Russia’s larger, pro-government news agencies also ranked highly, whilst the leading outlets in Western media (CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and the BBC) charted the lowest for retweets from retweet-heavy accounts.

Ukrainian news outlets such as Kyiv Post and UA Today TV also had below-average scores, as did the English-language accounts of Russian broadcasters such as Sputnik and RT. This contrasts sharply with the 42% rating of RT’s Russian language Twitter account—22% above the RuNet average. So what lay behind this disparity?

Taking a closer look at the metadata for the accounts that made up these retweet “farms,” an odd characteristic repeatedly emerged. In the field showing the name of the client software used to post tweets—which might usually be Twitter for Android or Tweetdeck—the same series of names showed up consistently: “bronislav,” “iziaslav,” “meceslav,” “slovoslav” and “rostislav.” Analysis showed that nearly half of the retweet bots used these clients.

Google searches suggested they weren’t associated with any known commercial Twitter software and appeared to be unique to the Russian bots, so it was highly likely they were part of a custom tool. Curiously, all of these names are traditional Slavic masculine names that variously derive from words describing “a person who fights for, or attains, glory.”

Using these client names as filters, I modified my Python code to flag only the accounts that posted using these software clients. This turned out to be a far more selective measure than retweet behavior alone; using the fine-tuned script, I isolated a total of 411 fake accounts.

Interestingly, the bots’ behavior changed over time. Although most are now dedicated to automated retweets, timeline searches show they previously promoted hashtags such as #AnarchyinUA, #PutinPeaceMaker, and #MaterialEvidence, often posting content similar to that seen on websites connected with the Internet Research Agency “troll farms.”

Over some time periods, as if in a stand-by or “idling” mode, the bots tweeted inspirational quotes or other content randomly lifted from the web.

RuNet-focused Bot Activity

Having obtained a “clean” sample of retweet bots that was free of false positives, I wanted to see which news agencies were getting the most attention from them. I wrote a third Python script to gather the usernames of the last 30 accounts retweeted by each bot, resulting in the following chart of top sources for bot retweets.

Russia’s larger state-backed news agencies and outlets—RIA Novosti, RT, LifeNews, and TASS—dominate the list. However, Twitter accounts of independent media organisations, such as Meduza Project and TV Rain, were also present. And oddly, while the account of Riafan (a website from the St. Petersburg “troll factory”-linked web network) was receiving fake retweets, so too was @champ_football (part of the sports site championat.com). It isn’t clear whether this strange combination is a quirk of the bots’ code or a deliberate attempt to disguise political intent. Either way, there is no evidence that any of the named organisations have ordered or orchestrated the retweets.

Data based on the client-source filter further confirms that the bots using what appears to be custom software focus almost entirely on Russian-language media (see graph).

There is no doubt that through their repeated retweets, these accounts are having a measurable impact on the Russian-speaking Twitter sphere and the traffic driven to the news websites. Their activity underlines how Twitter’s popularity and engagement scores can be artificially skewed, a factor of importance to social media analysts whose research may rely on such metrics.But retweets and hashtags are only a part of the bots’ payload. In my next article, I will examine the LiveJournal blogs they have been promoting en masse, and investigate whether they serve as evidence of a further attempt to disseminate pro-Kremlin content on the RuNet.

This story originally appeared on Global Voices and is re-published with the author’s permission.

Lawrence Alexander is a social science student. A member of UNA-UK and Hope not Hate, he writes for Global Voices on the political use of the internet and social media (@LawrenceA_UK).

Lawrence Alexander is a social science student. A member of UNA-UK and Hope not Hate, he writes for Global Voices on the political use of the internet and social media (@LawrenceA_UK).