Editor’s Note: In an era of increasing hostility to independent media, one of the bright spots is the rapid expansion of journalism nonprofits around the world — training, promoting, and reporting on stories that otherwise would never see the light of day. But a dangerous trend now threatens the progress our colleagues have made on press freedom and watchdog reporting: a crackdown on nonprofit organizations. Restrictions on international funding account for more than a third of the measures since 2012. With that in mind, we are pleased to reprint this important story from the Journal of Democracy, detailing the global scope of the backlash against civil society.

Editor’s Note: In an era of increasing hostility to independent media, one of the bright spots is the rapid expansion of journalism nonprofits around the world — training, promoting, and reporting on stories that otherwise would never see the light of day. But a dangerous trend now threatens the progress our colleagues have made on press freedom and watchdog reporting: a crackdown on nonprofit organizations. Restrictions on international funding account for more than a third of the measures since 2012. With that in mind, we are pleased to reprint this important story from the Journal of Democracy, detailing the global scope of the backlash against civil society.

Twenty years ago, the world was in the midst of an “associational revolution.” Civil society organizations (CSOs) enjoyed a mostly positive reputation within the international community, gained from their important contributions to health, education, culture, economic development, and a host of other objectives beneficial to the public. Political theorists, meanwhile, associated civil society with social justice, as exemplified by the U.S. civil-rights movement, the Central European dissident movements, and South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of the Internet, and the renaissance of civil society, many observers at the close of the twentieth century saw political, technological, and social developments interweaving to give rise to an era of civic empowerment. Reflecting this era, the UN General Assembly adopted in September 2000 the Millennium Declaration. Among its other provisions, the declaration trumpeted the importance of human rights and the value of “non-governmental organizations and civil society, in general.”

A year later, the global zeitgeist began to change. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, discourse shifted away from an emphasis on human rights and the positive contributions of civil society. U.S. president George W. Bush launched the War on Terror, and CSOs became an immediate target. “Just to show you how insidious these terrorists are,” Bush stated in his September 2001 remarks on the executive order freezing assets of terrorist and other organizations, “they oftentimes use nice-sounding, non-governmental organizations as fronts for their activities. . . . We intend to deal with them, just like we intend to deal with others who aid and abet terrorist organizations.” Shortly thereafter, Bush launched the Freedom Agenda, which included support for civil society as a key component. Because of the association of civil society with both terrorism and the Freedom Agenda, governments around the world became increasingly concerned about CSOs, particularly organizations that received international assistance.

This concern heightened after the so-called color revolutions. The 2003 Rose Revolution in Georgia roused Russia, but the turning point was the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine. Russian president Vladimir Putin viewed Ukraine as a battleground in the contest for geopolitical influence between Russia and the West. The Orange Revolution also caught the attention of other world leaders. As protesters flooded the streets of Kyiv, Belarus’s President Alyaksandr Lukashenka famously warned, “There will not be any rose, orange, or banana revolutions in our country.” During the same period, Zimbabwe’s parliament adopted a law restricting CSOs. Soon thereafter, Belarus enacted legislation restricting the freedoms of association and assembly. If there was a global associational revolution in 1994, by 2004 the global associational counterrevolution had begun.

Also contributing to this shift was the dwindling appetite for civil society support in countries that had undergone political transformations during the 1980s and 1990s. Years had passed, and these governments no longer considered themselves to be “in transition.” Rather, they had transitioned as far as they were inclined to go, and were now focused on consolidating governmental institutions and state power. This was particularly true in “semi-authoritarian” or “hybrid” regimes that held elections but had little interest in the rule of law, human rights, and other aspects of pluralistic democracy.

All this led numerous states to begin imposing restrictions on CSOs. Governments were able to coat these new constraints with a veneer of political theory. Those with autocratic tendencies touted variants of Putin’s theory of “managed democracy,” which seamlessly morphed into notions of “managed civil society.” Two models emerged in these countries: In some, CSOs were given latitude to operate, provided that they stayed away from politics. In others, the government sought to coopt CSOs and to shut down groups that resisted, particularly those that received international funding.

As a result of these and other factors, civic space quickly contracted.

According to data from the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), between 2004 and 2010 more than fifty countries considered or enacted measures restricting civil society. These restrictions were grounded in concerns about terrorism, foreign interference in political affairs, and aid effectiveness. These issues, coupled with the longstanding debate about the accountability and transparency of CSOs, provided governments with a potent cocktail of justifications to rationalize restrictions.

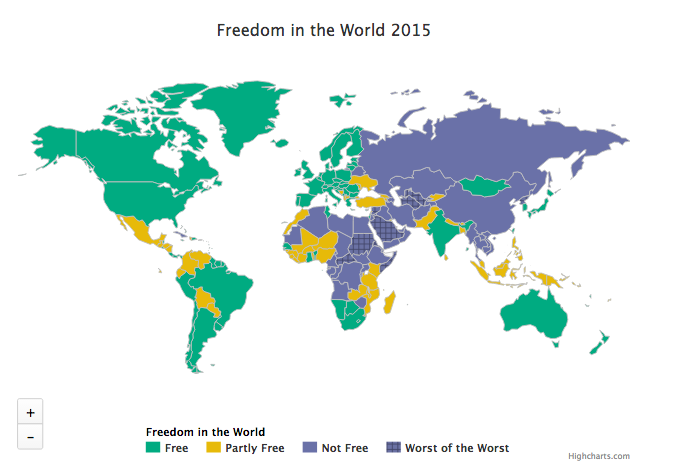

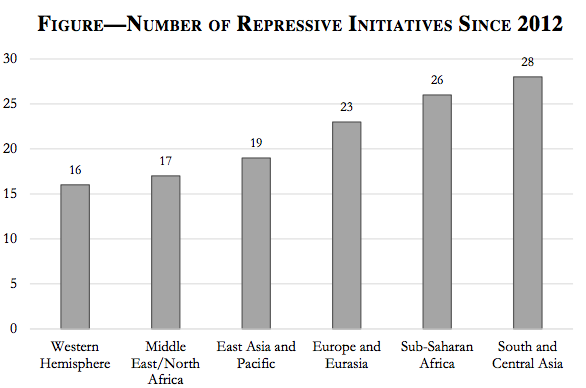

The Arab Spring, which began in late 2010, set off a second wave of legislative constraints. Once again, governments around the world took notice of these mass movements and initiated measures to restrict civil society in the hopes of preventing similar uprisings on their own soil. Since 2012, more than 120 laws constraining the freedoms of association or assembly have been proposed or enacted in 60 countries. This trend is consistent with the continuing decline in democracy worldwide. Freedom in the World 2015 reveals that 2014 was the ninth consecutive year of a global decline in freedom. As the Figure above (based on ICNL’s tracking data) shows, the restrictions of association and assembly, while more common in certain regions, is a global phenomenon.

Of these initiatives, approximately half could be called “framework” legislation: They constrain the incorporation, registration, operation, and general lifecycle of CSOs. Roughly 19 percent restrict the freedom of assembly. The greatest uptick, however, has been in restrictions on international funding, which now account for 35 percent of all restrictive measures.

The many legal and regulatory measures used by governments to curtail international funding include 1) requiring prior government approval for the receipt of international funding; 2) enacting “foreign-agents” legislation to stigmatize internationally funded CSOs; 3) capping the amount of international funding that a CSO is allowed to receive; 4) requiring international funding to be routed through government-controlled entities; 5) restricting activities that can be undertaken with international funding; 6) prohibiting CSOs from receiving international funding from specific donors; 7) constraining international funding through the overly broad application of anti–money laundering and counterterrorism measures; 8) taxing the receipt of international funding; 9) imposing onerous reporting requirements on the receipt of international funding; and 10) using defamation, treason, and other laws to bring criminal charges against recipients of international funding.

Darin Christensen and Jeremy M. Weinstein assessed the scale and scope of such restrictions as well as “the factors that account for variation in the incidence of foreign-funding restrictions” in these pages in 2013. I seek to build on this scholarly foundation by categorizing the various restrictions on CSOs, summarizing justifications for those restrictions, and analyzing such restrictions under international law.

Government Justifications

The justifications that governments use for enacting restrictions on CSOs fall into four broad categories: 1) protecting state sovereignty; 2) promoting transparency and accountability in the civil society sector; 3) enhancing aid effectiveness and coordination; and 4) pursuing national security, counterterrorism, and anti–money laundering objectives.

State sovereignty. Some governments invoke state sovereignty as a justification to restrict international funding. For example, in justifying the Russian foreign-agents law, Vladimir Putin stated, “The only purpose of this law after all was to ensure that foreign organisations representing outside interests, not those of the Russian state, would not intervene in our domestic affairs. This is something that no self-respecting country can accept.” Similarly, in July 2014 Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán lauded the establishment of a parliamentary committee to monitor civil society organizations: “We’re not dealing with civil society members but paid political activists who are trying to help foreign interests here. . . . It’s good that a parliamentary committee has been set up to monitor the influence of foreign monitors” on CSOs. In Egypt, 43 CSO staff members were charged in 2012 with “establishing unlicensed chapters of international organisations and accepting foreign funding to finance these groups in a manner that breached the Egyptian state’s sovereignty.” Egyptian officials claimed that the CSOs were contributing to international interference in the country’s domestic political affairs.

Some governments claim that foreigners are seeking not only to meddle in domestic political affairs, but actually to destabilize their countries or otherwise promote regime change. Accordingly, these governments argue that restrictions on international funding are necessary to thwart such efforts. In June 2015, for example, Pakistani authorities ordered Save the Children to leave the country, claiming that the aid organization was involved in “anti-Pakistan activities” and was “working against the country.” Although the decision was reversed days later, the interior minister warned, “Local NGOs that use foreign help and foreign funding to implement a foreign agenda in Pakistan should be scared. We will not allow them to work here whatever connections they enjoy, regardless of the outcry.”While Russia’s foreign-agents law was pending in parliament, one of its drafters stated, “There is so much evidence about regime change in Yugoslavia, now in Libya, Egypt, Tunisia, in Kosovo—that’s what happens in the world, some governments are working to change regimes in other countries. Russian democracy needs to be protected from outside influences.” In July 2014, the vice-chairman of the China Research Institute of China-Russia Relations argued that China should “learn from Russia” and enact a foreign-agents law “so as to block the way for the infiltration of external forces and eliminate the possibilities of a Color Revolution.”

Transparency and accountability. Another justification commonly invoked by governments to regulate and restrict the flow of foreign funds is the importance of upholding the integrity of CSOs by promoting transparency and accountability through government regulation. Consider, for example, the following responses by government delegations to a UN Human Rights Council panel on the promotion and protection of civil society held in March 2014: Ethiopia, on behalf of the African Group, stated, “Domestic law regulation consistent with the international obligations of States should be put in place to ensure that the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, assembly and association fully respects the rights of others and ensures the independence, accountability and transparency of civil society”; and India, on behalf of the Like Minded Group, stated, “The advocacy for civil society should be tempered by the need for responsibility, openness and transparency and accountability of civil society organizations.” Kyrgyzstan has used this same argument to justify its proposed foreign-agents law. The explanatory note to the draft law claims that it “has been developed for purposes of ensuring openness, publicity, [and] transparency for nonprofit organizations.”

Aid effectiveness and coordination. A global movement advocating greater effectiveness of international development assistance has steadily been gaining strength. Strategies for achieving such improvement include promoting “host-country ownership” and harmonizing development assistance. Some states, however, have interpreted host-country ownership to mean host-government ownership, and have otherwise exploited the aid-effectiveness campaign to justify constraints on international funding.

For example, in July 2014 Nepal’s government released its Development Cooperation Policy, which requires development partners to channel all assistance through the Ministry of Finance, rather than directly to CSOs. The Ministry of Finance stated that this was necessary in order to maximize aid efficiency: “Both the Government and the development partners are aware of the fact that the effectiveness can only be enhanced if the ownership of aid funded projects lies with the recipient government.”That same month, Sri Lanka’s Finance and Planning Ministry issued a public notice requiring CSOs to receive government approval of international funding. The ministry justified the move by claiming that projects financed with international funding were “outside the government budget undermining the national development programmes.” The year before, Egypt’s government had similarly argued that government coordination of aid was necessary in order to mitigate the negative effects of having multiple CSOs at work in the country.

National security, counterterrorism, and anti–money laundering. Governments sometimes invoke national security, counterterrorism, and anti–money laundering aims in order to justify imposing restrictions on international funding, including cross-border philanthropy. China’s government defended draft legislation restricting international funding by insisting that the law was intended to safeguard China’s “national security and social stability.” Azerbaijan’s government, meanwhile, justified amendments relating to the registration of foreign grants by claiming that the amendments were meant “to enforce international obligations of the Republic of Azerbaijan in the area of combating money-laundering.”And in the British Virgin Islands, CSOs with more than five employees are required by law to appoint a designated Money Laundering Reporting Officer and submit to audit requirements not imposed on businesses. These burdens were supposedly based on the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force’s recommendation on nonprofit organizations and counterterrorism.

The International Legal Framework

International norms and laws provide a framework for the protection of civil society, while also allowing for exceptions that permit national governments to enact restrictions under certain circumstances and adhering to specified conditions.

Global norms. Article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) states, “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others.” According to Maina Kiai, UN Special Rapporteur (UNSR) on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, “The right to freedom of association not only includes the ability of individuals or legal entities to form and join an association but also to seek, receive and use resources—human, material and financial—from domestic, foreign and international sources.”

The UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders similarly states that access to resources is a self-standing right: “Everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, to solicit, receive and utilize resources for the express purpose of promoting and protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms through peaceful means.” Furthermore, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, this right specifically encompasses “the receipt of funds from abroad.”

Regional and bilateral commitments to protect international funding. International funding for civil society is also protected at the regional level. Take, for example, the Council of Europe Recommendation on the Legal Status of NGOs, which states, “NGOs should be free to solicit and receive funding—cash or in-kind donations—not only from public bodies in their own state but also from institutional or individual donors, another state or multilateral agencies.” Likewise, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “states should allow and facilitate human rights organizations’ access to foreign funds in the context of international cooperation, in transparent conditions.”

Many jurisdictions also have concluded bilateral investment treaties that help to protect the free flow of capital across borders. Some treaties, such as the U.S. treaties with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, respectively, expressly extend investment-treaty protections to organizations not “organized for pecuniary gain.” The letters from the White House transmitting these treaties to the U.S. Senate explicitly state that they cover “charitable and non-profit entities.”

Restrictions permitted under international law. International law allows a government to restrict access to resources if three conditions are met: The restriction is 1) prescribed by law; 2) in pursuance of one or more legitimate aims; and 3) “necessary in a democratic society” to achieve those aims.

1) Prescribed by law. The first condition requires restrictions to have a formal basis in law. This means that “restrictions on the right to freedom of association are only valid if they had been introduced by law (through an act of Parliament or an equivalent unwritten norm of common law), and are not permissible if introduced through Government decrees or other similar administrative orders.” Yet the aforementioned Nepalese and Sri Lankan policies affecting foreign assistance to CSOs were based on executive actions and not “introduced by law (through an act of Parliament or an equivalent unwritten norm of common law).” Thus they seem to violate the “prescribed by law” standard required under both the Council of Europe’s Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and the ICCPR. Douglas Rutzen 35 Moreover, according to international law, restrictions must be “‘prescribed by law,’ which implies that the law must be accessible and its provisions must be formulated with sufficient precision.” In other words, a provision must be sufficiently precise for an individual or NGO to understand whether or not its intended conduct would constitute a violation of law. This requirement helps to limit the scope of permissible restrictions. For example, some laws ban the funding of organizations that cause “social anxiety,” have a “political nature,” or have “implied ideological conditions.” Because these terms are undefined and provide little guidance to individuals or organizations about what is and is not prohibited, however, it can be reasonably argued that they fail the “prescribed by law” requirement.

2) Legitimate aims. The second condition requires that restrictions must advance at least one legitimate aim—specifically, national security or public safety; public order; the protection of public health or morals; or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. This provides a useful lens through which to analyze the various justifications that governments use to defend constraints on civil society. As noted above, some governments have cited the enhancement of “aid effectiveness” as a reason for imposing restrictions on CSOs. But, as a UNSR report states, aid effectiveness “is not listed as a legitimate ground for restrictions.” Similarly, “the protection of State sovereignty is not listed as a legitimate interest in the [ICCPR],” and “States cannot refer to additional grounds . . . to restrict the right to freedom of association.”

Of course, assertions of national security or public safety may, in certain circumstances, constitute a legitimate aim. Under the Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the ICCPR, however, assertions of national security must be construed restrictively “to justify measures limiting certain rights only when they are taken to protect the existence of the nation or its territorial integrity or political independence against force or threat of force.” In addition, a state may not use “national security as a justification for measures aimed at suppressing opposition . . . or at perpetrating repressive practices against its population.” This includes defaming or stigmatizing foreign-funded groups by accusing them of “treason” or “promoting regime change.”

3) Necessary in a democratic society. In a 2012 report, UNSR Maina Kiai wrote that “longstanding jurisprudence asserts that democratic societies only exist where ‘pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness’ are in place,” and “minority or dissenting views or beliefs are respected.”Accordingly, unless a restriction is “necessary in a democratic society,” it violates international law even if the government is able to articulate a legitimate aim. Elaborating on this point, the Guiding Principles of Freedom of Association of the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights states that the necessity requirement does not have “the flexibility of terms such as ‘useful’ or ‘convenient’: instead, the term means that there must be a ‘pressing social need’ for the interference.”

A 2013 UNSR report notes that governments frequently justify constraints with a rhetorically appealing term such as “sovereignty,” “counterterrorism,” or “accountability and transparency,” which upon inspection proves to be merely “a pretext to constrain dissenting views or independent civil society” in violation of international law. With regard to counterterrorism efforts, the report states, “In order to meet the proportionality and necessity test, restrictive measures must be the least intrusive means to achieve the desired objective and be limited to the associations falling within the clearly identified aspects characterizing terrorism only. They must not target all civil society associations.” With regard to the aid-effectiveness justification, the report concludes that “deliberate misinterpretations by Governments of ownership or harmonization principles to require associations to align themselves with Governments’ priorities contradict one of the most important aspects of freedom of association, namely that individuals can freely associate for any legal purpose.” But as one civil society representative in China told the Washington Post, “The target is not the money, it is the NGOs themselves. The government wants to control NGOs by controlling their money.”

Several recent studies examining constraints on international funding and the political environments in which they arise support the UNSR’s assertions. One study found that in most countries where political opposition is unhindered and voting is conducted in a “free and fair” manner, international funding restrictions generally are not imposed on CSOs. By contrast, in countries where election manipulation takes place, governments tend to restrict CSO access to foreign support, fearing that well-funded CSOs could contribute to their defeat at the polls. In other words, vulnerable regimes hoping to cling to power sometimes restrict international funding in order to weaken the opposition.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, many countries saw the importance of defending civil society. Today, however, many countries are defunding civil society. Using all sorts of pretexts, governments that feel threatened by such organizations impose restrictions on them. These governments are able to do so in part because the cornerstone concepts of civil society are still being developed, debated, and—at times—violently contested. The outcome of this debate will shape the future of civil society for decades to come.

Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Democracy, October 2015. The full paper, Authoritarianism Goes Global (II): Civil Society Under Assault (with footnotes), can be accessed here.

Douglas Rutzen is CEO of the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL). He is an adjunct professor of law at Georgetown University and serves on the Community of Democracies’ Working Group on Enabling and Protecting Civil Society.