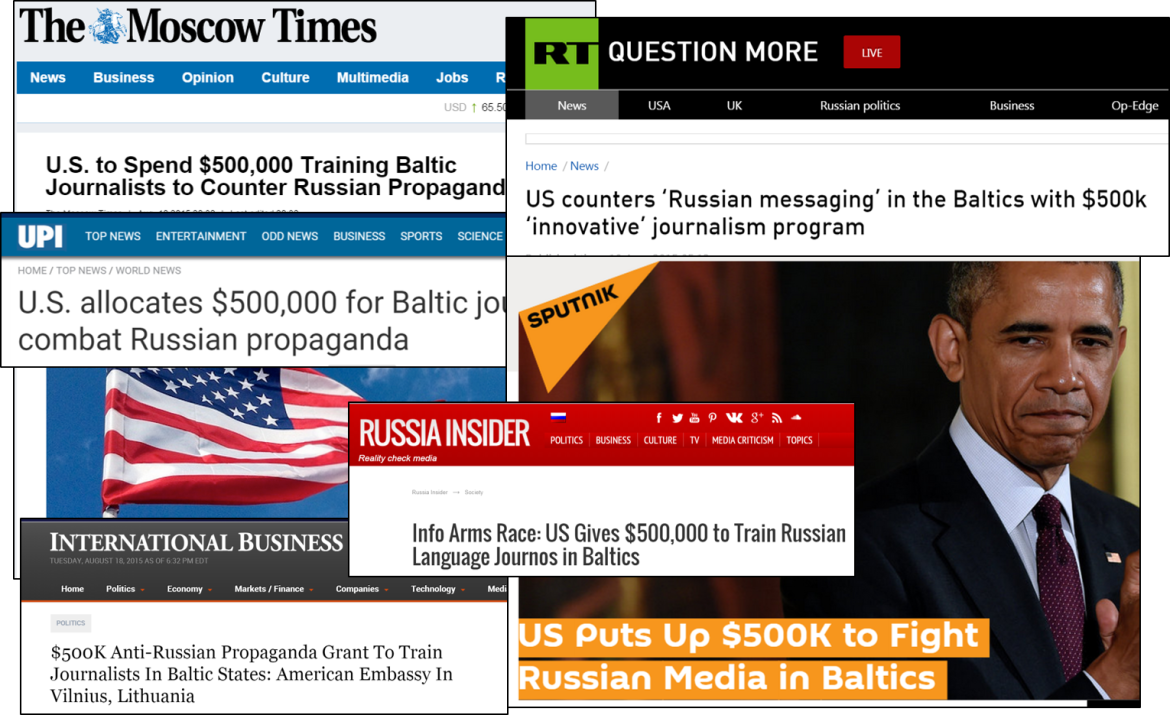

As a rule, media development grants are not news. But a number of Russia’s leading newspapers, including Izvestia and Moscow Times, reported last week that the U.S. Embassy in Lithuania (@USEmbVilnius) has announced that $500,000 is being made available to regional media organizations to combat Russian propaganda. Izvestia pointed to the grant as proof that the U.S. Government is also involved in propaganda and have called the grant anti-Russian.

As a rule, media development grants are not news. But a number of Russia’s leading newspapers, including Izvestia and Moscow Times, reported last week that the U.S. Embassy in Lithuania (@USEmbVilnius) has announced that $500,000 is being made available to regional media organizations to combat Russian propaganda. Izvestia pointed to the grant as proof that the U.S. Government is also involved in propaganda and have called the grant anti-Russian.

Although not widely known, Western governments — including the United States — are the largest donors to media. They spend tens of millions of dollars per year to help promote independent media, often through grants to large media development organizations in developing and transitioning countries around the world. The support has been instrumental in promoting fair and balanced media around the world.

Propaganda or Independent Media: A U.S. embassy funding notice errs by confusing investigative journalism with infowar.

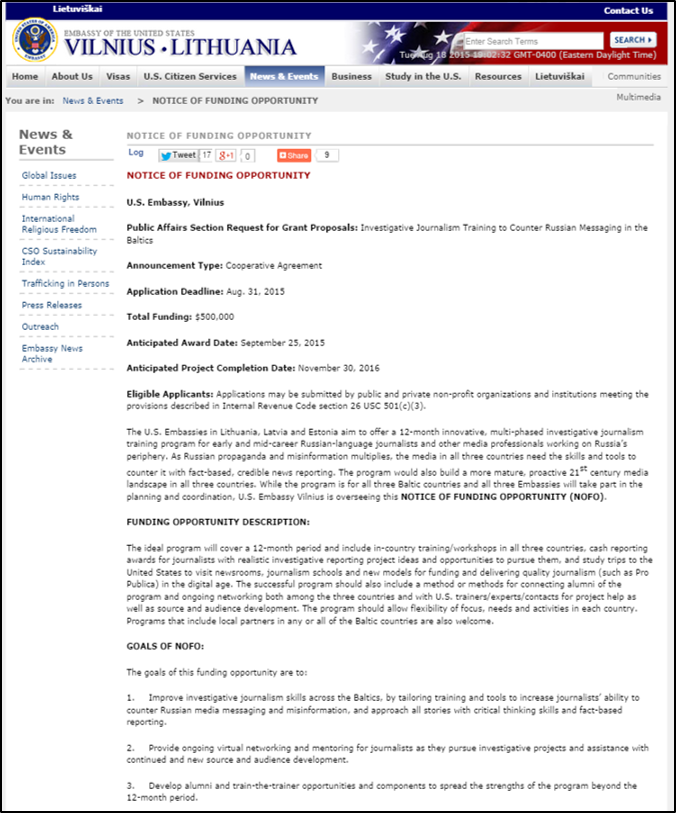

The hefty Lithuania grant is unusual for an embassy, and already the big media development companies are sniffing around the region trying to sign up local partners. But they may have problems. A number of the region’s larger and more investigative journalism-oriented organizations are staying away, including the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), Re:Baltica in Riga, 15min.lt in Vilnius, and the Center for Media Studies at Stockholm School of Economics in Riga, all veterans of reporting in the Baltics.

The problem starts with the grant title: “Investigative Journalism Training to Counter Russian Messaging in the Baltics.” The title implies the grant seeks journalists to actively counter a Russian message which, at best, is not a mission for journalism and, at worst, is propaganda itself. While the detailed description of the grant is more neutral, the title was seized on by pro-Russian media immediately.

And herein lies the fundamental challenge that policy makers in Europe and the U.S. face: Russian propaganda is real. In the Baltics and elsewhere there are large Russian-speaking minorities living next to local populations. In some of these communities, they get their news from Moscow and not local media. If they watch major media, that news often consists of scripts pushed by the Kremlin – a steady drumbeat of wholesale lies, imagined slights to Russia and Russianness, conspiracy theories about the West’s plans to undermine Mother Russia, odd reinterpretations of the Ukraine war (where the Ukrainians attacked the Russians) and other mythologies.

While these seem laughable to Western readers, these stories are very effective not only in Russia but in the many Russian-speaking areas of surrounding countries. The news fits a consistent world view promoted for more than a decade by the popular and slickly produced Russian media industry. Western governments fear that the propaganda will be used to foment dissent in the Baltics, Moldova, the Caucasus, and other countries caught between the East and West. At the heart of the problem is that no one really understands Putin’s intentions, but after Ukraine they know what he is capable of.

This has caused governments bordering Russia to rethink their indifference to the effects of Russian media. Discussions have been ongoing between governments, and the Lithuanian grant is one of many similarly themed initiatives getting underway. European governments and other donors want to counter the propaganda. Their plans already underway include new Russian-language television channels with counter-messages, new journalism centers to promote excellence, and new hubs to repackage Russian and regional independent media work. More efforts are likely.

There is a fear among the journalism community that governments will respond to propaganda with more propaganda. That is not a solution. It will only serve to alienate Russian readers and prove Mr. Putin’s allegations that the West is doing the same. It will also hurt real media by splitting audiences.

And that is the key. Any plan must do no harm and that means not hurting the existing independent media. Some of these plans have not been properly vetted to make sure they don’t do this. Media is about building trust and credibility. New media creations with poor or short term goals and no credibility will immediately be tagged as propaganda and will fail with readers while simultaneously hurting existing media. The best organizations to counter propaganda are the independent media organizations that have been telling the truth, often at great personal risk, for more than a decade. Ways must be found to support the needs of these organizations directly or indirectly.

A group of media organizations is now banding together to have a say in this process that, until now, has largely been driven by donors and media development organizations with often different interests. A meeting is scheduled by the SSE Riga for September to bring these media together to explain to donors and implementers what is needed — and not the other way around.

The grant offered by the Lithuanian embassy, when you read the details, does not appear to have bad intentions. It’s a typical training grant aimed at improving skills. But the poor choice of wording on the title makes it impossible for serious organizations to bid. We encourage them to rewrite and reissue the grant.

The reality is that the independent mediascape in the former Soviet space is in dire straits. But these same independent media are also the most credible source of information to readers from the region, especially to those likely to question the propaganda. Replacing them with expensive (and unsustainable) new media won’t work, and asking them to counter propaganda will damage them. The solution is to recommit ourselves to supporting independent and non-profit media. It’s not an easy path but it’s the only sustainable solution. Sometimes the only path is hard.

Update: On August 20, the U.S. Embassy in Lithuania removed language suggesting that this grant was a counter-propaganda program. The new language, “Investigative Journalism Training Program in the Baltics,” better reflects what is apparently the aim of the grant — to encourage independent journalism that is professional, fair, and accurate.

Drew Sullivan is a veteran journalist and media development specialist who has worked for a decade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. He founded the Center for Investigative Reporting in Bosnia-Herzegovina and served as its director and editor. He co-founded the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Program, a regional consortium of investigative centers, where he is now advising editor.

Drew Sullivan is a veteran journalist and media development specialist who has worked for a decade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. He founded the Center for Investigative Reporting in Bosnia-Herzegovina and served as its director and editor. He co-founded the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Program, a regional consortium of investigative centers, where he is now advising editor.