Editor’s Note: We are pleased to run this excerpt from The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom by Joel Simon, executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. This is the full introduction to the book, starting in Islamabad and laying out the extraordinary challenges facing the news media in the 21st Century.

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to run this excerpt from The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom by Joel Simon, executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. This is the full introduction to the book, starting in Islamabad and laying out the extraordinary challenges facing the news media in the 21st Century.

We arrived in Pakistan’s capital, Islamabad, on May 1, 2011, two days in advance of our scheduled meeting with President Asif Ali Zardari. Bob Dietz, a veteran journalist who had covered wars in Somalia and Lebanon and edited a magazine in Hong Kong before becoming the Asia program coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists, had done the advance work, arranging our schedule and preparing our agenda. Paul Steiger and I were the other members of the team. Steiger was the managing editor at The Wall Street Journal in 2001 when reporter Daniel Pearl was kidnapped and killed in Pakistan. It was this terrible experience that led Steiger to become involved in the fight for global press freedom and eventually to become the chairman of CPJ. In May 2007, Steiger stepped down from the Journal and started up an innovative media non-profit called ProPublica dedicated to carrying out investigative journalism in the public interest. We hoped to capitalize on Steiger’s personal history to shame the Pakistani authorities into action.

Journalists gather outside Osama Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad after the U.S. raid. Photo c/o Flickr.

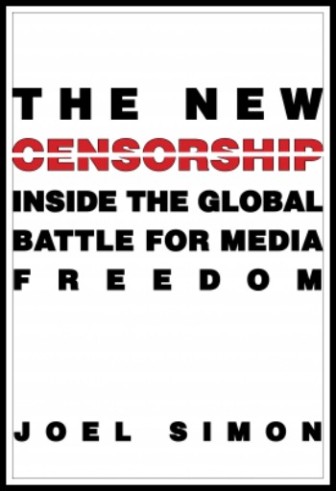

While intensive international pressure had led to the arrest and conviction of several people involved in the Pearl killing, 15 journalists had been murdered subsequently, all of them Pakistani. No convictions had been obtained in any of those cases. In order to reinforce this point, we had compiled a report on those murdered that we had provocatively labeled “A Dossier of Death.” Our plan was to deliver it directly to the president and secure from him a public commitment to fully investigate the crimes.

All of our careful planning was thrown into disarray when we awoke on May 2 to a huge global news story: A commando unit of Navy Seals had infiltrated Pakistan and carried out a daring raid that killed Osama Bin Laden. While we were not in Pakistan to cover the Bin Laden raid, being in the midst of the one of the biggest global news stories in recent history gave me a fascinating window into the way our evolving system of global information functions.

Overnight a Pakistani engineer in Abbottabad — the garrison town where Bin Laden had holed up with his wives and children – had sent out a curious tweet about a helicopter crash at a compound on the outskirts of town. Much was made of the fact that Bin Laden story raid had broken on Twitter, but this was highly misleading. Without context the one tweet was essentially meaningless. It was only when Pakistani journalists arrived on the scene that information began to flow. Pakistan has several vibrant and powerful cable news channels. Amidst the burning wreckage of the downed helicopter, I watched breathless correspondents deliver standups in Urdu. Occasionally, tidbits of information in English would appear on the crawl at the bottom of the screen.

As the morning progressed our hotel began to fill with international journalists making their way to Abbottabad, which was described in initial international news reports as “just outside the capital of Islamabad” but was actually a two-hour drive away. The raid had clearly caught officials completely off guard and in the disarray journalists swarmed the city, interviewing neighbors and climbing hillsides to take photos of Bin Laden’s compound and the remains of the crashed helicopter.

We also saw from our close up vantage point how international media coverage distorted and misinterpreted the local reality, and this lack of clear information made it more difficult for us to make informed decisions about basic issues like our own security. The initial coverage suggested that throngs of Pakistani were about to pour into the streets to express their outrage and indignation over the U.S. raid and their support for Bin Laden. Not surprisingly, we received flurries of emails from home suggesting that as foreigners we were in imminent danger and should hightail it out of town.

But by working our contacts in the Pakistani media we were quickly able to discern that street protests were unlikely. Such protests are not generally spontaneous outpourings, but are organized by political parties, factions, or religious groups who mobilize their supporters. The political environment was not conducive to such mobilizations at a time when most of the public anger was directed not toward the United States, but toward the Pakistani military and intelligence establishment that had been humiliated by the raid. While the streets of the Islamabad were in fact empty, the international cable networks I watched from my hotel room used images of a small public protest in Karachi on heavy rotation. When I visited Karachi a few days later, a friend and journalist who lives there and took me on a sightseeing tour of the city was dismissive of the media portrayal. “There are protests in Karachi every day,” he told me.

The Pakistani government’s strategy, meanwhile, was to project an atmosphere of business as usual. So our May 3 meeting with President Zardari was reconfirmed. The pressing desire for normalcy was highlighted by our hotel restaurant, which went ahead with its scheduled “Mexican night” featuring tacos and enchiladas, but not Coronas, this being Pakistan.

The role of Pakistani journalists in covering the Bin Laden story reinforced the importance of our presidential meeting because it had given us a close-up view of the absolutely critical role played by the Pakistani media. It was the Pakistani journalists who were the first to record the dramatic events in Abbottabad and it was Pakistani reporters who, after the deluge of foreign correspondents had gone home, were left to report on subsequent developments, to analyze and agitate, and to interpret Pakistan for a global audience. This was not to say that the Pakistani media is exemplary; far from it, the press features plenty of rumor mongering, shoddy reporting, drivel, and craven attacks orchestrated by political forces. But at least the information was flowing, debate was raging, and powerful institutions that had escaped criticism were facing heightened scrutiny. Pakistani journalists recognized just how vulnerable they were in this environment. Several prominent media figures had called the president on our behalf to lobby for our meeting. We owed it to them to extract as much as we could.

The next morning at the appointed hour we climbed into a rented Toyota Land Cruiser and drove all of five minutes through silent streets lined with the usual barricades and police checkpoints. At the presidential palace, we were escorted into a large reception area, and from there into the formal receiving room where chairs had been lined up in rows facing each other. The government delegation, consisting of the Interior Minister, the Information Minister, and a number of other advisors, filed in and took their seats on one side. We sat opposite.

President Zardari entered and sat in a raised chair placed between the two rows. Steiger introduced our delegation and spoke about the comfort he took from the vigorous investigation that Pakistani authorities carried out into the killing of Danny Pearl. While making clear that many suspects in that case remain at large, Steiger contrasted the response to the Pearl killing with the complete lack of investigation into the murders of 15 Pakistani journalists killed subsequently, all of them local reporters. Dietz handed the president the “Dossier of Death” report, which reinforced our point that Pakistan was not only one of the most deadly countries in the world for the media but also had one of the world’s worst records for bringing the murderers of journalists to justice. These two facts were linked, as it is the failure to solve previous crimes that perpetuated the climate of violence.

President Zardari entered and sat in a raised chair placed between the two rows. Steiger introduced our delegation and spoke about the comfort he took from the vigorous investigation that Pakistani authorities carried out into the killing of Danny Pearl. While making clear that many suspects in that case remain at large, Steiger contrasted the response to the Pearl killing with the complete lack of investigation into the murders of 15 Pakistani journalists killed subsequently, all of them local reporters. Dietz handed the president the “Dossier of Death” report, which reinforced our point that Pakistan was not only one of the most deadly countries in the world for the media but also had one of the world’s worst records for bringing the murderers of journalists to justice. These two facts were linked, as it is the failure to solve previous crimes that perpetuated the climate of violence.

The president seemed surprised, and over the course of our meeting he spoke about the considerable challenges that Pakistan faces – from the lack of resources, to the ongoing threat of terrorism. Zardari asked us what other countries confronting violence against journalists had done. I told him that a firm commitment from the country’s leadership was a prerequisite to addressing the issue and spoke specifically about Colombia and Brazil, two countries in Latin America that had made progress in achieving convictions. The president responded by asking Interior Minister Rehman Malik to provide us with detailed information on the status of the outstanding cases. He also asked his cabinet members to work with Parliament to develop new legislation to strengthen press freedom. The president then shook hands and quickly left the meeting.

The commitment from the head of state was significant, although we were well aware that Zardari was politically isolated and that real power in Pakistan rests with the military and the shadowy Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI. Complicating our efforts was the fact that the ISI itself is alleged to have been involved in a number of targeted attacks on the media, including the December 2005 kidnapping and murder of Hayatullah Khan. Khan, a photographer, writer, and stringer for a number of international news organizations was abducted in North Waziristan after taking photos showing fragments of a U.S.-made Hellfire missile used to kill Al-Qaeda militant Hamza Rabia. The photo, and the story Khan published along with it, contradicted the official Pakistani government explanation that Rabia had died when a bomb he was building in his house exploded.

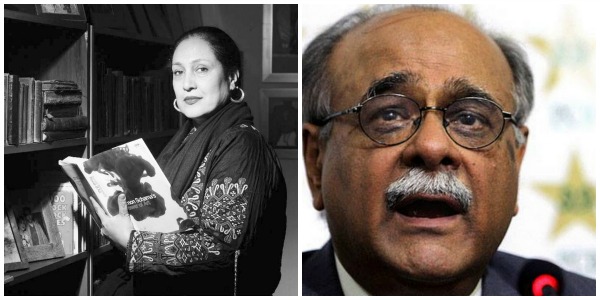

A few days after our meeting with President Zardari, I traveled to Lahore to visit my friends Najam Sethi and Jugnu Mohsin, two of Pakistan’s best known journalists. They were living under threat of death, and their elegant brick home had become a virtual fortress surrounded by armed guards. Despite this, I found them in a state of agitation and high excitement. Sethi had flown in that afternoon from Islamabad where he and 18 television news anchors had been given a briefing by the top military brass including army chief of staff General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and Lt. Gen Ahmed Shuja Pasha, then head of the ISI (Pasha retired in March 2012 and Kayani retired in November 2013). Shockingly, Sethi recounted, the generals first heard about the U.S. raid when a journalist from the national cable broadcaster GEO TV called the ISI to find out if one of their helicopters had crashed in Abbottabad. ISI officials then called the military, and only when they both realized that the helicopter did not belong to either of them did they deploy troops to the scene. By that time the U.S. ground operation was over. The Pakistani air force scrambled fighter jets with an order to attack the intruders but the Americans made it back across the border into Afghanistan.

Two of Pakistan’s best known journalists: Jugnu Mohsin, left; Najam Sethi, right.

For Sethi, the fact that top generals were compelled to explain themselves to the Pakistani media was an unprecedented and welcome development. The reason that the generals invited the nation’s top anchors for a sit down was because in the aftermath of the Bin Laden killing they had completely lost control of the country’s information agenda. The nationalist commentators were attacking the military and the ISI as incompetent for failing to defend the country’s sovereignty against the U.S. invasion. They were calling for commissions of inquiry, questioning the military budget, and intonating that Pasha and Kayani should step down. Sethi’s criticism was different. He believed that government policy of supporting militant groups, including the Taliban, was wrongheaded and detrimental to Pakistan’s national interest. His personal anger focused on the fact that Bin Laden was living comfortably in a military garrison town with apparent high-level protection.

Sethi and Mohsin had begun their journalism careers as editor and publisher (and founders) of The Friday Times, a leading English-language weekly aimed squarely at the country’s intellectual elite. The paper had earned a respectable circulation and was read and discussed by the top political and military leaders as well as by the business and diplomatic communities but to Sethi’s great disappointment its political influence was limited. In 2002 former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf liberalized ownership rules for cable television channels, partly as a political move to counter the influence and popularity of Indian satellite channels that were widely available in Pakistan. The result was an explosion of television news channels across the country. Sethi was invited to host an interview and opinion program and his television show gave him a visibility, reach, and influence that he had never previously enjoyed.

Sethi’s sense of being able to influence the national debate was amplified in the aftermath of the Bin Laden killing when, for the first time in recent memory and perhaps ever, the press turned on the military and the ISI, demanding accountability. But while the generals were providing an unprecedented level of access, they were also sending a strong and ominous message about the limits of acceptable criticism. Pakistani journalists are routinely summoned to have “tea” with ISI officials, who criticize their reporting while simultaneously warning them of threats. In the aftermath of the Bin Laden raid, the frequency and stridency of the meetings increased. The clear message was that the media had crossed the line and their continued impertinence would not be tolerated.

On May 29, two weeks after the CPJ delegation left Pakistan, journalist Saleem Shahzad was intercepted on the streets of Islamabad while on his way to a television interview. Shahzad, 40, was a veteran reporter who started on the crime beat in Karachi in the 1990s working for the daily The Star and later branched out into coverage of political and military issues. He was abducted a few days after his report was published on the Web site Asia Online detailing how Al-Qaeda had infiltrated the Pakistan Navy. After its double agents were exposed, Al-Qaeda carried out a reprisal attack on May 17 against a highly secure Naval Base in Karachi that left 10 dead and destroyed two surveillance plane purchased from the United States. Shahzad had also recently published a book on the militant networks and their links to the ISI called Inside Al Qaeda and the Taliban. Following an October 17 meeting with ISI officials in which he was threatened, Shahzad sent an email to Human Rights Watch Pakistan director Ali Dayan Hasan to be made public in the case of his death.

Shahzad’s body was recovered on May 30 in a drainage canal about two hours outside of Islamabad. He had been beaten to death; his liver was ruptured and he suffered two broken ribs. Widespread suspicion that he was abducted and killed by the ISI was confirmed by an unnamed U.S. official who told The New York Times, “[T]his was a deliberate, targeted killing that was most likely meant to send shock waves through Pakistan’s journalist community and civil society.” According to Dexter Filkins writing in The New Yorker, the order to kill Shahzad came from a senior officer on General Kayani’s staff. The ISI denied any involvement, calling Shahzad’s murder “unfortunate and tragic,” but noting ominously that it should not be “used to target and malign the country’s security agency.”

Over the next few weeks, several other prominent journalists were threatened and forced to leave the country. Sethi, who had already been warned by the ISI that he was under threat, obtained specific evidence of a conspiracy to kill him involving the banned militant group Lakshi-e-Taiba that had close ties to elements in the ISI. In August 2011, Sethi accepted a three-month appointment as a senior advisor with the New America Foundation and he and Mohsin moved to Washington, D.C. There was no follow up on the commitments from President Zardari and we never heard more from Rehman Malik’s office about the investigations into journalists’ killings. The message the ISI seemed to be sending was that no amount of international and domestic outcry would deter them in their efforts to ensure that the media stayed within the boundaries they had drawn for acceptable criticism.

Over the next few weeks, several other prominent journalists were threatened and forced to leave the country. Sethi, who had already been warned by the ISI that he was under threat, obtained specific evidence of a conspiracy to kill him involving the banned militant group Lakshi-e-Taiba that had close ties to elements in the ISI. In August 2011, Sethi accepted a three-month appointment as a senior advisor with the New America Foundation and he and Mohsin moved to Washington, D.C. There was no follow up on the commitments from President Zardari and we never heard more from Rehman Malik’s office about the investigations into journalists’ killings. The message the ISI seemed to be sending was that no amount of international and domestic outcry would deter them in their efforts to ensure that the media stayed within the boundaries they had drawn for acceptable criticism.

I took the murder of Saleem Shahzad very personally because I felt his killing was the ISI’s answer to our efforts to stand up for Pakistani journalists and keep them safe. It made me feel angry and helpless.

The efforts to control the news in the aftermath of the Bin Laden killing also highlighted the complexity and vulnerability of the system of global information that has evolved in the Internet age. Yes, the Internet has spawned an unprecedented transformation in the way that global news is gathered and disseminated and immensely facilitated certain kinds of reporting, specifically of protests and demonstrations which are now routinely documented through social media. But the Bin Laden raid, despite the excitement about the initial tweet from Abbottabad, was not reported on social media. It was covered the old-fashioned way by reporters on the ground who provided both first hand accounts and informed analysis based on years on experience and deep contacts. Journalists covering front-line stories are routinely murdered not just in Pakistan, but in Russia, Pakistan, and the Philippines.

Despite the communication revolution spawned by technology, the collective access to the essential information we need in a globalized world to make informed decisions about our lives and our future is by no means assured. State repression against the media is on the rise, often hidden behind a democratic façade. The Internet itself, which has obviously become the key piece of infrastructure in the global news system, is threatened by increasingly effective national censorship regimes in places like China and Iran and undermined by revelations of the unprecedented global surveillance effort carried by the U.S. National Security Agency.

Today, we live in a world in which the old information order dominated by large and powerful media corporations has been upended, transformed by a new system in which technology has enabled individuals and loosely configured organizations to participate in the process of gathering and disseminating news on a global scale. The endless debate over which system is better is a massive distraction. The reality is that we live in a hybrid system in which the traditional media – local newspapers and radio, national broadcasters, magazines and dailies, and powerful global media organizations – exist alongside new forms of communications including citizen journalism, blogging, and even more informal information networks, such as person-to-person texting. Each plays a vital role.

The traditional media is certainly diminished, but it remains essential to bringing information to a mass audience. Meanwhile, precisely because there are fewer international correspondents, the front-line news-gatherers are increasingly freelancers, local journalists working in their own country, human rights activists, and average people with cell phones. It’s not an either/or scenario, and it’s not necessarily a pretty picture, but the reality is that we depend on the ability of both the old and new systems to operate simultaneously and interact with one another to deliver the news we need. The current system is jury-rigged and fragile and the challenge of ensuring that access to global information is strengthened and expanded is exacerbated by the fact that the system continues to evolve.

The New Censorship describes this new global information order, analyzes the threats, and proposes steps that need to be taken to keep the vital flow of information open. My goal is not to predict the future of the media or to fit the current messy reality into some neat paradigm. Rather I seek to describe the system as it exists today, identify the challenges, and outline the strategies that we can employ to meet them. We need to fight both to keep the Internet open and to ensure justice for journalists who are killed. We need to deploy new technologies to help people in repressive societies circumvent censorship and fight to get imprisoned journalists out of jail. More broadly, we need a robust international framework that recognizes the crucial role that information plays in the new global order and provides redress for people everywhere who are unable to access the information to which they are legally entitled.

Independent media of one form or another has played a critical role in many of the seminal events of the last half-century: The collapse of the Soviet Union; the restoration of democracy in Latin America; the economic transformation of Asia; to recent Arab uprisings. But in today’s globalized, interconnected world, free and unfettered information is more essential than ever. It’s essential for markets and for trade. And it’s essential to empowering the emerging community of global citizens and ensuring that they are able to participate in a meaningful way in the decisions that affect their lives. Likewise, those who are deprived of information are essentially disempowered. We live in a world in which the abundance of information obscures the enormous gaps in our knowledge created by violence, repression, and state censorship. Ensuring that news and information circulates freely throughout societies and across borders is the challenge of our time.

Joel Simon is executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and has written widely on media issues. He is a regular contributor to Slate and the Columbia Journalism Review, and his articles have appeared in the New York Review of Books, New York Times, and other publications. He is also author of Endangered Mexico: An Environment on the Edge.

Joel Simon is executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and has written widely on media issues. He is a regular contributor to Slate and the Columbia Journalism Review, and his articles have appeared in the New York Review of Books, New York Times, and other publications. He is also author of Endangered Mexico: An Environment on the Edge.