Umar Cheema

How do you cover corruption in Pakistan’s national security agencies? With caution and plenty of guts. Such reporting got investigative journalist Umar Cheema kidnapped, tortured, and nearly killed in 2010, but the founder of the Center for Investigative Reporting in Pakistan hasn’t backed down. “Reporting on corruption is a painful experience,” he says, but it is also a calling.

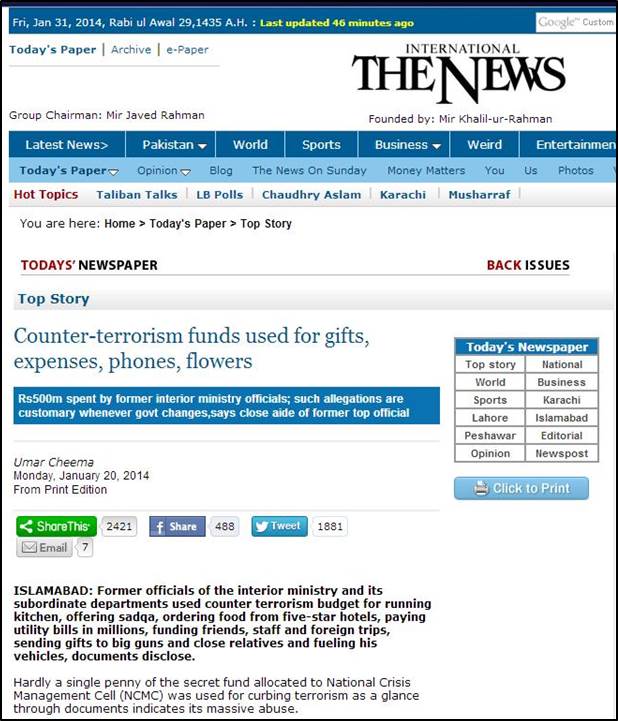

Check out the latest from the Islamabad-based Cheema, who last week revealed that elite counter-terrorism officials used a secret agency fund to buy wedding gifts, luxury carpets, and gold jewelry for relatives of ministers and visiting dignitaries. Here’s the original story Cheema wrote, for Pakistan’s The News:

The documents Cheema dug up were obtained by Agence France Presse, which then added intriguing details in a story several days later:

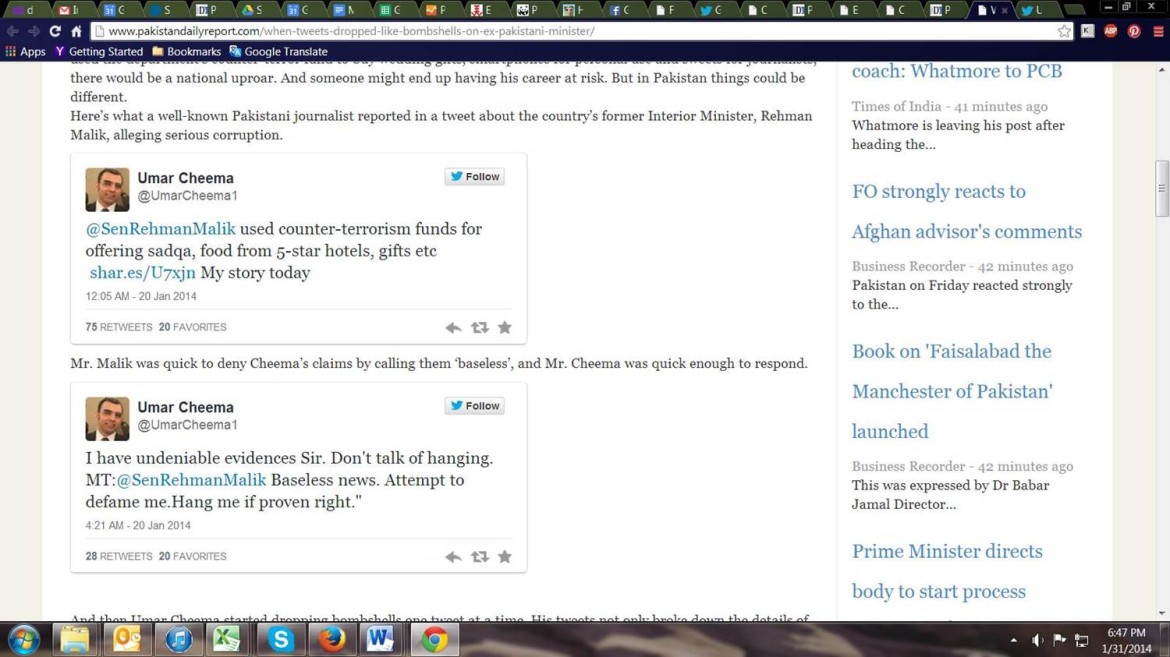

One of those implicated in the documents, former Interior Minister Rehman Malik, was none too happy about the story, claiming that Cheema’s work is financed by the Taliban and that authorities should “hang me if proven right.” Cheema pushed back through his 93,000-plus Twitter following: “I have undeniable evidences Sir. Don’t talk of hanging,” he tweeted. Here’s a bit of the back-and-forth, with the full exchange published by The Pakistani Daily Report:

“If, in the U.S., an investigative journalist with over 90,000 twitter followers claimed that an ex homeland security chief used the department’s counter-terror fund to buy wedding gifts, smartphones for personal use and sweets for journalists, there would be a national uproar,” suggested the Daily Report. “And someone might end up having his career at risk.”

“But in Pakistan things could be different.”

We asked Umar Cheema if this kind of reaction comes with the job in Pakistan. Here’s what he said:

Is this business as usual for you?

Cheema: Sadly, yes. Instead of contesting the news content, intentions are questioned in order to distract attention from the issue under question. End result: one requires a lot of effort to move on things (holding them to account). Ironically, the current interior minister is also reluctant to order an inquiry. Auditors are being denied the documents requisitioned for conducting an audit of the counter-terrorism funds.

When I released tax reports in 2012 revealing that 67% lawmakers were non-filers, a lot of energy was spent to discredit the report, terming it a conspiracy against democracy. Many of the non-taxpaying lawmakers were found investigating the source of funding of the report. The intended purpose was to link it with a foreign agenda to divert attention from the tax-evasion malpractices.

So this kind of response just comes with the turf?

Cheema: It is just a tip of the iceberg. Many wheels within wheels. Such funds have also been used for purchasing bulletproof vehicles for the personal security of different authorities. In some cases, kickbacks were received in-kind from the foreign companies involved in the business of security equipment. Many big names will be named.

Pakistan has unfortunately become a crisis country led by those experts in converting the tragedies into personal opportunities. Weeks ago, I reported about Pakistan’s disaster management agency. Among other irregularities, its chief pressurized a UN body, the FAO, for recruiting his son who didn’t have the requisite experience for the intended position. When the FAO refused, its project that was to be executed through the disaster management agency was delayed. Work on it resumed only after induction of the son in the project to be executed by the agency headed by the father.

Reporting on corruption is a painful experience. A country mired in crisis is ruled by an elite bent on ruining it for vested interests. But on a positive note, this sorry affair has given me a reason to do journalism for the betterment of my country. I often wonder, what if I had not been a journalist.